Date:

October 18, 1973

Location: Mansfield, Ohio, United States

The

Coyne case (or "Army helicopter incident") stands

out as, perhaps the most credible (in the "high strangeness"

category) of the 1973 wave. An Army Reserve helicopter

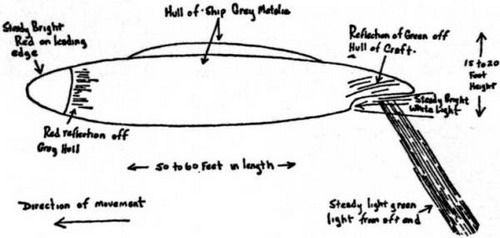

crew of four men encountered a gray, metallic-looking,

cigar-shaped object, with unusual lights and maneuvers,

as they were airborne between Columbus and Cleveland,

Ohio.

Source:

Jennie Zeidman, CUFOS

The

Coyne case (or "Army helicopter incident") stands

out as, perhaps the most credible (in the "high strangeness"

category) of the 1973 wave. An Army Reserve helicopter

crew of four men encountered a gray, metallic-looking,

cigar-shaped object, with unusual lights and maneuvers,

as they were airborne between Columbus and Cleveland,

Ohio. The crew won the NATIONAL ENQUIRER Blue Ribbon Panel's

$ 5,000 award for "the most scientifically valuable

report of 1973."

On

October 18, 1973, at approximately 10:30 PM a UH-1H helicopter

of the United States Army Reserve left Port Columbus,

Ohio, for its home base of Cleveland Hopkins airport,

ninety-six nautical miles to the north-northeast. In command,

in the right-front seat, was Captain Lawrence J. Coyne,

thirty-six, with nineteen years of flying experience.

At the controls, in the left-front seat, sat First Lieutenant

Arrigo Jezzi, twenty-six, a chemical engineer. Behind

Jezzi sat Sergeant John Healey, thirty-five, a Cleveland

policeman who was the flight medic, and Coyne was the

Crew Chief, Sergeant Robert Yanacsek, twenty-three, a

computer technician. The helicopter was cruising at 2,500

feet above sea level at an indicated airspeed of ninety

knots, above mixed hills, woods, and rolling farmland,

averaging 1,200 elevation. The night was totally clear,

calm, and starry. The last quarter moon was just rising.

About

ten miles south of Mansfield, Healey noticed a single

red light off to the west, flying south. It seemed brighter

than a standard aircraft port-wing light, but it was not

considered relevant traffic, and he does not recall mentioning

it. An estimated two minutes later, at approximately 11:02

PM, Yanacsek noted a single red light on the south-east

horizon. He assumed it was either a radio-tower beacon

or an aircraft port-wing light - most likely an aircraft,

since it was not flashing - and he watched it "for

a long time, a minute to ninety seconds" before calling

it to Coyne's attention. Coyne, smoking, relaxing, glanced

over, noted the light, assumed it was distant traffic,

and told told Yanacsek casually to "keep an eye on

it."

After

an estimated additional thirty seconds, Yanacsek announced

that the light had turned toward the helicopter and appeared

to be on a converging flight path. Coyne verified Yanacsek's

assessment, grabbed the controls from Jezzi, and put the

UH-1H into a powered descent of approximately 500 feet

per minute. Almost simultaneously, Coyne established radio

contact with Mansfield control tower, ten miles to the

northwest. Coyne thought the flight was an Air National

Guard F-100 from Mansfield. After an initial acknowledgment

("This is Mansfield Tower, go ahead Army 1-5-triple-4"),

radio contact failed. Jezzi then attempted transmission

on both UHF and VHF frequencies without success. Although

the channel and keying tones were both heard, there was

no response from Mansfield; and a subsequent check by

Coyne revealed that Mansfield had no tape of even the

initial transmission, the the last F-100 had landed at

10:47 P.M.

The

red light continued its radial bearing and increased greatly

in intensity. Coyne increased his rate of descent to 2,000

feet per minute and his airspeed to 100 knots. The last

altitude he noted was 1,700 feet. Just as a collision

appeared imminent, the unknown light halted in its westward

course and assumed a hovering relationship above and in

front of the helicopter. "It wasn't cruising, it

was stopped. For maybe ten to twelve seconds - just stopped,"

Yanacsek reported. Coyne, Healey, and Yanacsek agree that

a cigar-shaped, slightly domed object substended an angle

of nearly the width of the front windshield. A featureless,

gray, metallic-looking structure was precisely delineated

against the background stars. Yanacsek reported "a

suggestion of windows" along the top dome section.

The red light emanated from the bow, a white light became

visible at a slightly indented stern, and then, from aft/below,

a green 'pyramid shaped" beam equated to a directional

spotlight became visible. The green beam passed upward

over the helicopter nose, swung up through the windshield,

continued upward and entered the tinted upper window panels.

At that point (and not before), the cockpit was enveloped

in green light. Jezzi reported only a bright white light,

comparable to the leading light of a small aircraft, visible

through the top "greenhouse' panels of the windshield.

After the estimated ten seconds of "hovering,"

the object began to accelerate off to the west, now with

only the white "tail" light visible. The white

light maintained its intensity even as its distance appeared

to increase, and finally (according to Coyne and Healey),

it appeared to execute a decisive 45 degree turn to the

right, head out toward Lake Erie, and then "snap

out" over the horizon. Healey reported that he watched

the object moving westward "for a couple of minutes."

Jezzi said it moved faster than the 250-knot limit for

aircraft below 10,000 feet, but not as fast as the 600-knot

approach speed reported by the others. There was no noise

from the object or turbulence during the encounter, except

for one "bump" as the object moved away to the

west. After the object had broken off its hovering relationship,

Jezzi and Coyne noted that the magnetic compass disk was

rotating approximately four times per minute and that

the altimeter read approximately 3,500 feet; a 1,000 foot-per-minute

climb was in progress. Coyne insists that the collective

was still bottomed from his evasive descent. Since the

collective could not be lowered further, he had no alternative

but to lift it, whatever the results, and after a few

seconds of gingerly maneuvering controls (during which

the helicopter reached nearly 3,800 feet), positive control

was achieved. By that time the white light had already

moved into the Mansfield area. Coyne had been subliminally

aware of the climb; the others not at all, yet they had

all been acutely aware of the g-forces of the dive. The

helicopter was brought back to the flight plan altitude

of 2,500 feet, radio contact was achieved with Canton/Akron,

the night proceeded uneventfully to Cleveland.

Apparent

ground witnesses to this event have been found by William

E. Jones and Warren Nicholson, independent UFO researchers

from Columbus, Ohio.

Mrs.

E. C. and four adolescents were driving south from Mansfield

to their rural home on October 18, 1973, at approximately

11 P.M., when they were attracted to a single steady bright

red light. flying south "at medium altitude."

They watched for perhaps half a minute until it disappeared

to the south over the trees.

Approximately

five minutes later, now driving east on Route 430, approaching

the Charles Mill Reservoir, the family became aware of

two bright lights - red and green - descending rapidly

toward them from the southeast. When first seen, the angular

distance between the lights was about 2 degrees; the red

light appeared to be leading. Mrs. C. pulled over to the

shoulder of the deserted road and kept the engine and

car lights running. The lights - bigger than point sources

- slowed and moved as a unit to the right of the car and

the family became aware of yet another group of lights

- some of these flashing - and "a beating sound,

a lot of racket" approaching from the southwest.

Two of the children (cousins, both age thirteen) jumped

from the car and observed both a helicopter and the object,

which they described as "like a blimp," "as

big as a school bus," "sort of pear shaped."

The object at that point subtended an angle equivalent

to "a 100-mm cigarette box held at arm's length."

The object assumed a hovering position over the helicopter,

an estimated 500 feet back from the road and 500 feet

above the trees. (The ground elevation at the site is

almost exactly 1,000 feet above sea level; thus at the

noted 1,700-foot altimeter reading, the helicopter was

actually about 650 feet above the trees.) The object's

green light then flared up. "It was like rays coming

down," the witnesses said. The helicopter, the trees,

the road, the car - everything turned green." The

kids scrambled with fright back into the car and Mrs.

C. proceeded apace. Their estimated total time outside

the car was "about a minute." Neither ground

witnesses nor aircrew are sure at what point the two aircraft

disengaged; the ground witnesses reported that the unidentified

object crossed to the north side of the road behind the

car, appeared to move eastward for a few seconds, then

reversed its direction and climbed toward the northwest

towards Mansfield - a flight path which correlates perfectly

the motion of the object established through analysis

of the aircrew's report.

Any

theory of the object's being a meteor (UFO skeptic Philip

Klass maintains that the object was a "fireball of

the Orionid meteor shower") can readily be rejected

on the basis of: (1) the duration of the event (an estimated

300 seconds); (2) the marked deceleration and hard-angle

maneuver of the object at closest approach; (3) the precisely

defined shape of the object; and (4) the horizon-to-horizon

flight path.

The

possibility of a high-performance aircraft likewise is

untenable when one examines the positions and colors of

the lights with respect to the flight path of the object.

To have presented the reported configurations, and been

in accordance with FAA regulations, an aircraft would

have had to be flying sideways, either standing on its

tail, tail-to to the helicopter, or upside-down head-on.

Other arguments against aircraft hypothesis are: (1) a

fixed-wing aircraft moving across the line of sight would

appear to move most rapidly when passing directly in front

of the observer; (2) a fixed-wing aircraft would not have

the capability of decelerating from high velocity to "hover"

within a few seconds time; (3) a helicopter would have

the capability of hovering, but would not be capable of

the high forward speeds reported; (4) a conventional aircraft,

if within 500 to 1,000 feet, would have produced noise

audible inside the helicopter; (5) the FAA requires either

a strobe or a rotating beacon on either the top or bottom

of the fuselage, (6) FAA requires that no aircraft shall

fly below 10,000 feet msl at speeds above 250 knots; (7)

some of the features of a conventional aircraft would

have been seen, e.g., wings, engine pods, windows, empennage,

numbers, logo.

Coyne

reported that the Magnaflux/Zygio method of nondestructive

testing was applied to the rotors the following day and

that there was no indication that they had been subjected

to fatigue-producing stresses. Comparable times/distances/directions

support the possibility that the red light first seen

by the C. family, Healey's red light, and the object of

the encounter were all one and the same. Yanacsek's red

light on the eastern horizon was under continuous observation

and was unequivocally the object of the encounter.

The

case has maintained its high "strangeness-credibility"

rating after extended investigation and analysis.

Jennie

Zeidman

CUFOS

Source:

http://www.ufoevidence.org/cases/case104.htm