Donald

Howard Menzel (April 11, 1901 – December 14, 1976)

was one of the first theoretical astronomers and astrophysicists

in the US. He discovered the physical properties of the

solar chromosphere, the chemistry of stars, the atmosphere

of Mars, and the nature of gaseous nebulae.

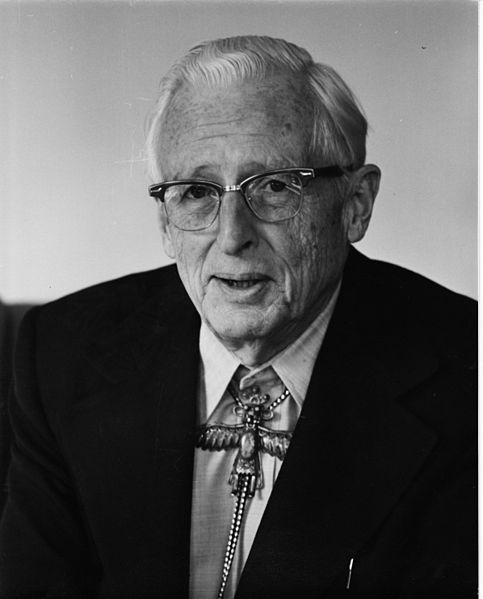

Donald Howard Menzel by Babette Whipple

Biography

Born

in Florence, Colorado in 1901 and raised in Leadville,

he learned to read very early, and soon could send and

receive messages in Morse code, taught by his father.

He loved science and mathematics, collected ore and rock

specimens, and as a teenager he built a large (and probably

hazardous) chemistry laboratory in the cellar. He made

a radio transmitter - no kits in those days - and qualified

as a radio ham. He was an Eagle Scout, specializing in

Cryptanalysis, as well as an outdoorsman, hiking and fly

fishing throughout much of his life. He married Florence

Elizabeth Kreager on June 17, 1926 and had two daughters

(Suzanne Kay and Elizabeth Ina).

At

16, he enrolled in the University of Denver to study chemistry.

His interest in astronomy was aroused through a boyhood

friend (Edgar Kettering), through observing the solar

eclipse of June 8, 1918, and through observing the eruption

of Nova Aquilae 1918 (V603 Aquilae). He graduated from

the University of Denver in 1920 with an A.B. degree in

chemistry and an A.M. degree in chemistry and mathematics

in 1921. He also found summer positions in 1922, 1923,

and 1924 as research assistant to Harlow Shapley at the

Harvard College Observatory. At Princeton University he

acquired a second A.M. degree in astronomy in 1923, and

in 1924 a Ph.D. in astrophysics for which his advisor

was Henry Norris Russell, who inspired his interest in

theoretical astronomy. After teaching two years at the

University of Iowa and Ohio State University, in 1926

he was appointed assistant Professor at Lick Observatory

in San Jose CA, where he worked for several years. In

1932, he moved to Harvard. During World War ll, Menzel

was asked to join the Navy as Lieut. Commander, to head

a division of intelligence, where he used his many-sided

talents, including deciphering enemy codes. Even until

1955, he worked with the Navy improving radio-wave propagation

by tracking the sun's emissions and studying the effect

of the aurora on radio propagation for the Department

of Defense (Menzel & Boyd, p. 60). Returning to Harvard

after the war, he was appointed acting director of the

Harvard Observatory in 1952, and was the full director

from 1954 to 1966. The term "Menzel Gap" was

used to refer to the absence of astronomical photographic

plates during a brief period in the 1950s when plate-making

operations were temporarily halted by Menzel as a cost-cutting

measure. He retired from Harvard in 1971. From 1964 to

his death, Menzel was a U.S. State Department consultant

for Latin American affairs.

He

received honorary A.M. and Sc.D. degrees from Harvard

University in 1942 and the University of Denver in 1954

respectively. From 1946-1948 he was the Vice President

of the American Astronomical Society, becoming their President

from 1954-1956. In 1965, Menzel was given the John Evans

Award of the University of Denver. In May 2001, Harvard-Smithsonian

Center for Astrophysics hosted the "Donald H. Menzel:

Scientist, Educator, Builder," a symposium in honor

of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Donald H. Menzel.

Menzel

is renowned for traveling with expeditions to view solar

eclipses to obtain scientific data. On 19 June 1936, he

led the Harvard-MIT expedition to the steppes of Russia

(at Ak Bulak in southwestern Siberia) to observe a total

eclipse. For the 9 July 1945 eclipse, he directed the

Joint U.S.-Canadian expedition to Saskatchewan, although

they were clouded out. Menzel observed many total solar

eclipses, often leading the expeditions, including Catalina

California (10 September 1923, cloudy), Camptonville California

(28 April 1930), Freyburg Maine (31 August 1932), Minneapolis-St.

Paul Minnesota (30 June 1954), the Atlantic coast of Massachusetts

(2 October 1959), northern Italy (15 February 1951), Orono

Maine (20 July 1963, cloudy), Athens/Sunion Road, Greece

(20 May 1966), Arequipa Peru (12 November 1966), Miahuatlan,

south of Oaxaca, Mexico (7 March 1970), Prince Edward

Island Canada (10 July 1972), and western Mauritania (30

June 1973), in addition to the other three mentioned above.

In

the late 1930s he built an observatory for solar research

at Climax CO, using a telescope that mimicked a total

eclipse of the sun, allowing him and his colleagues to

study the sun's corona and to film the spouting flames,

called prominences, emitted by the sun. Menzel initially

performed solar research, but later concentrated on studying

gaseous nebulae. His work with Lawrence Aller and James

Gilbert Baker defined many of the fundamental principles

of the study of planetary nebulae. He wrote the first

edition (1964) of A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets,

part of the Peterson Field Guides. In one of his last

papers, Menzel concluded, based on his analysis of the

Schwarzschild equations, that black holes do not exist,

and he declared them to be a myth.

Menzel

and UFOs

In

addition to his academic and popular contributions to

the field of astronomy, Menzel was a prominent skeptic

concerning the reality of UFOs. He authored or co-authored

three popular books debunking UFOs: Flying Saucers - Myth

- Truth - History (1953), The World of Flying Saucers

(1963, co-authored with Lyle G. Boyd), and The UFO Enigma

(1977, co-authored with Ernest H. Taves). All of Menzel's

UFO books argued that UFOs are nothing more than misidentification

of prosaic phenomena such as stars, clouds and airplanes;

or the result of people seeing unusual atmospheric phenomena

they were unfamiliar with. He often suggested that atmospheric

hazes or temperature inversions could distort stars or

planets, and make them appear to be larger than in reality,

unusual in their shape, and in motion. In 1968, Menzel

testified before the U.S. House Committee on Science and

Astronautics - Symposium on UFOs, stating that he considered

all UFO sightings to have natural explanations.

He

was perhaps the first prominent scientist to offer his

opinion on the matter, and his stature doubtless influenced

the mainstream and academic response to the subject. Perhaps

Menzel's earliest public involvement in UFO matters was

his appearance on a radio documentary directed and narrated

by Edward R. Murrow in mid-1950. (Swords, 98)

Menzel

had his own UFO experience when he observed a 'flying

saucer' while returning on 3 March 1955 from the North

Pole on the daily Air Force Weather "Ptarmigan"

flight. His account is in both Menzel & Boyd and Menzel

& Taves. He later identified it as a mirage of Sirius,

but Steuart Campbell claims that it was a mirage of Saturn.

Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Howard_Menzel