Edward

Teller (January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was

a Hungarian-born American theoretical physicist, known

colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb",

even though he claimed he did not care for the title.

Teller made numerous contributions to nuclear and molecular

physics, spectroscopy (the Jahn–Teller and Renner–Teller

effects), and surface physics. His extension of Fermi's

theory of beta decay (in the form of the so-called Gamow–Teller

transitions) provided an important stepping stone in the

applications of this theory. The Jahn–Teller effect

and the BET theory have retained their original formulation

and are still mainstays in physics and chemistry. Teller

also made contributions to Thomas–Fermi theory, the

precursor of density functional theory, a standard modern

tool in the quantum mechanical treatment of complex molecules.

In 1953, along with Nicholas Metropolis and Marshall Rosenbluth,

Teller co-authored a paper which is a standard starting

point for the applications of the Monte Carlo method to

statistical mechanics.

Teller

emigrated to the United States in the 1930s, and was an

early member of the Manhattan Project charged with developing

the first atomic bombs. During this time he made a serious

push to develop the first fusion-based weapons as well,

but these were deferred until after World War II. After

his controversial testimony in the security clearance

hearing of his former Los Alamos colleague J. Robert Oppenheimer,

Teller was ostracized by much of the scientific community.

He continued to find support from the U.S. government

and military research establishment, particularly for

his advocacy for nuclear energy development, a strong

nuclear arsenal, and a vigorous nuclear testing program.

He was a co-founder of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

(LLNL), and was both its director and associate director

for many years.

Edward Teller in 1958 as Director of the

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

In

his later years he became especially known for his advocacy

of controversial technological solutions to both military

and civilian problems, including a plan to excavate an

artificial harbor in Alaska using thermonuclear explosive

in what was called Project Chariot. He was a vigorous

advocate of Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative. Throughout

his life, Teller was known both for his scientific ability

and his difficult interpersonal relations and volatile

personality, and is considered one of the inspirations

for the character Dr. Strangelove in the 1964 movie of

the same name.

Early

life and education

Teller

was born in Budapest, Hungary (then Austria-Hungary),

into a Jewish family, in the year 1908. His parents were

Ilona (née Deutsch), a pianist, and Max Teller,

an attorney. When he was very young, his grandfather told

his mother not to be too unhappy that he was apparently

an idiot, because he hadn't spoken by the age of three.

A doctor suggested he might be mentally retarded. Teller

had no interest in speaking because his father spoke Hungarian

and very poor German, and his mother spoke German and

very poor Hungarian. As a result, he decided that they

didn't know what they were talking about[citation needed].

Despite being raised in a Jewish family, he later on became

an agnostic. He became very interested in numbers, and

would calculate in his head large numbers, such as the

number of seconds in a year.

.jpg)

Teller in his youth

He

left Hungary in 1926 (partly due to the numerus clausus

rule under Horthy's regime). The political climate and

revolutions in Hungary during his youth instilled a lingering

animosity for both Communism and Fascism in Teller. When

he was a young student, his right foot was severed in

a streetcar accident in Munich, requiring him to wear

a prosthetic foot and leaving him with a lifelong limp.

Teller graduated in chemical engineering at the University

of Karlsruhe and received his Ph.D. in physics under Werner

Heisenberg at the University of Leipzig. Teller's Ph.D.

dissertation dealt with one of the first accurate quantum

mechanical treatments of the hydrogen molecular ion. In

1930 he befriended Russian physicists George Gamow and

Lev Landau. Teller's lifelong friendship with a Czech

physicist, George Placzek, was very important for Teller's

scientific and philosophical development. It was Placzek

who arranged a summer stay in Rome with Enrico Fermi for

young Teller, thus orienting his scientific career in

nuclear physics.

Teller

spent two years at the University of Göttingen, and

left in 1933 through the aid of the International Rescue

Committee. He went briefly to England, and moved for a

year to Copenhagen, where he worked under Niels Bohr.

In February 1934, he married Augusta Maria "Mici"

(pronounced "Mitzi") Harkanyi, the sister of

a longtime friend.

In

1935, thanks to George Gamow's incentive, Teller was invited

to the United States to become a Professor of Physics

at George Washington University (GWU), where he worked

with Gamow until 1941. Prior to the discovery of fission

in 1939, Teller was engaged as a theoretical physicist,

working in the fields of quantum, molecular, and nuclear

physics. In 1941, after becoming a naturalized citizen

of the United States, his interest turned to the use of

nuclear energy, both fusion and fission.

At

GWU, Teller predicted the Jahn–Teller effect (1937),

which distorts molecules in certain situations; this affects

the chemical reactions of metals, and in particular the

coloration of certain metallic dyes. Teller and Hermann

Arthur Jahn analyzed it as a piece of purely mathematical

physics. In collaboration with Brunauer and Emmet, Teller

also made an important contribution to surface physics

and chemistry: the so-called Brunauer–Emmett–Teller

(BET) isotherm.

When

World War II began, Teller wanted to contribute to the

war effort. On the advice of the well-known Caltech aerodynamicist

and fellow Hungarian émigré Theodore von

Kármán, Teller collaborated with his friend

Hans Bethe in developing a theory of shock-wave propagation.

In later years, their explanation of the behavior of the

gas behind such a wave proved valuable to scientists who

were studying missile re-entry.

Manhattan

Project

In

1942, Teller was invited to be part of Robert Oppenheimer's

summer planning seminar at the University of California,

Berkeley for the origins of the Manhattan Project, the

Allied effort to develop the first nuclear weapons. A

few weeks earlier, Teller had been meeting with his friend

and colleague Enrico Fermi about the prospects of atomic

warfare, and Fermi had nonchalantly suggested that perhaps

a weapon based on nuclear fission could be used to set

off an even larger nuclear fusion reaction. Even though

he initially explained to Fermi why he thought the idea

would not work, Teller was fascinated by the possibility

and was quickly bored with the idea of "just"

an atomic bomb (even though this was not yet anywhere

near completion). At the Berkeley session, Teller diverted

discussion from the fission weapon to the possibility

of a fusion weapon — what he called the "Super"

(an early version of what was later to be known as a hydrogen

bomb).

On

December 6, 1941, the United States had begun development

of the atomic bomb, under the supervision of Arthur Compton,

chairman of the University of Chicago physics department,

who coordinated uranium research with Columbia University,

Princeton University, University of Chicago, and University

of California, Berkeley. Eventually, Compton transferred

the Columbia and Princeton scientists to the Metallurgical

Laboratory at Chicago, and Enrico Fermi moved in at the

end of April 1942 and the construction of Chicago Pile

1 began. Teller was left behind at first, but then called

to Chicago two months later. In early 1943, the Los Alamos

laboratory was built to design an atomic bomb under the

supervision of Oppenheimer in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Teller moved there in April 1943.

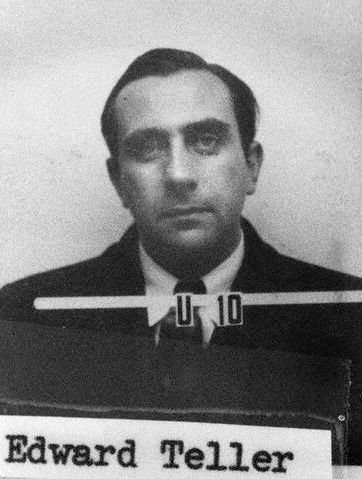

Teller's ID badge photo from Los Alamos

Teller

became part of the Theoretical Physics division at the

then-secret Los Alamos laboratory during the war, and

continued to push his ideas for a fusion weapon even though

it had been put on a low priority during the war (as the

creation of a fission weapon was proving to be difficult

enough by itself). Because of his interest in the H-bomb,

and his frustration at having been passed over for director

of the theoretical division (the job was instead given

to Hans Bethe), Teller refused to engage in the calculations

for the implosion mechanism of the fission bomb. This

caused tensions with other researchers, as additional

scientists had to be employed to do that work—including

Klaus Fuchs, who was later revealed to be a Soviet spy.

Apparently, Teller managed to also irk his neighbors by

playing the piano late in the night. However, Teller made

valuable contributions to bomb research, especially in

the elucidation of the implosion mechanism. He also was

one of the few scientists to actually watch (with eye

protection) the first test detonation in July 1945, rather

than follow orders to lie on the ground with backs turned.

He later said that the atomic flash "was as if

I had pulled open the curtain in a dark room and broad

daylight streamed in."

In

1946, Teller participated in a conference in which the

properties of thermonuclear fuels such as deuterium and

the possible design of a hydrogen bomb were discussed.

It was concluded that Teller's assessment of a hydrogen

bomb had been too favourable, and that both the quantity

of deuterium needed, as well as the radiation losses during

deuterium burning, would shed doubt on its workability.

Addition of expensive tritium to the thermonuclear mixture

would likely lower its ignition temperature, but even

so, nobody knew at that time how much tritium would be

needed, and whether even tritium addition would encourage

heat propagation. At the end of the conference, in spite

of opposition by some members such as Robert Serber, Teller

submitted an unduly optimistic report in which he said

that a hydrogen bomb was feasible, and that further work

should be encouraged on its development. Fuchs had also

participated in this conference, and transmitted this

information to Moscow. The model of Teller's "classical

Super" was so uncertain that Oppenheimer would later

say that he wished the Russians were building their own

hydrogen bomb based on that design, so that it would almost

certainly retard their progress on it.

In

1946, Teller left Los Alamos to return to the University

of Chicago as a professor and close associate of Enrico

Fermi and Maria Mayer. He was now known as the father

of the hydrogen bomb.

Hydrogen

bomb

Following

the Soviet Union's first test detonation of an atomic

bomb in 1949, President Truman announced a crash development

program for a hydrogen bomb. Teller returned to Los Alamos

in 1950 to work on the project. He insisted on involving

more theorists, such as Klaus Fuchs; it was Fuchs who

later claimed to invent compression by means of radiation

implosion back in 1946. However many of Teller's prominent

colleagues, like Bethe and Oppenheimer, were sure that

the project of the H-bomb was technically infeasible and

politically undesirable. None of the available designs

were yet workable. However Soviet scientists who had worked

on their own hydrogen bomb have claimed that they developed

it independently.

In

1950, calculations by the Polish mathematician Stanislaw

Ulam and his collaborator Cornelius Everett, along with

confirmations by Fermi, had shown that not only was Teller's

earlier estimate of the quantity of tritium needed for

the H-bomb a low one, but that even with higher amounts

of tritium, the energy loss in the fusion process would

be too great to enable the fusion reaction to propagate.

However, in 1951, in the joint report by Ulam and Teller

of March 1951, "Hydrodynamic Lenses and Radiation

Mirrors", an innovative idea emerged, and it was

developed into the first workable design for a megaton-range

H-bomb. The exact contribution provided respectively from

Ulam and Teller to what became known as the Teller–Ulam

design is not definitively known in the public domain,

and the exact contributions of each and how the final

idea was arrived upon has been a point of dispute in both

public and classified discussions since the early 1950s.

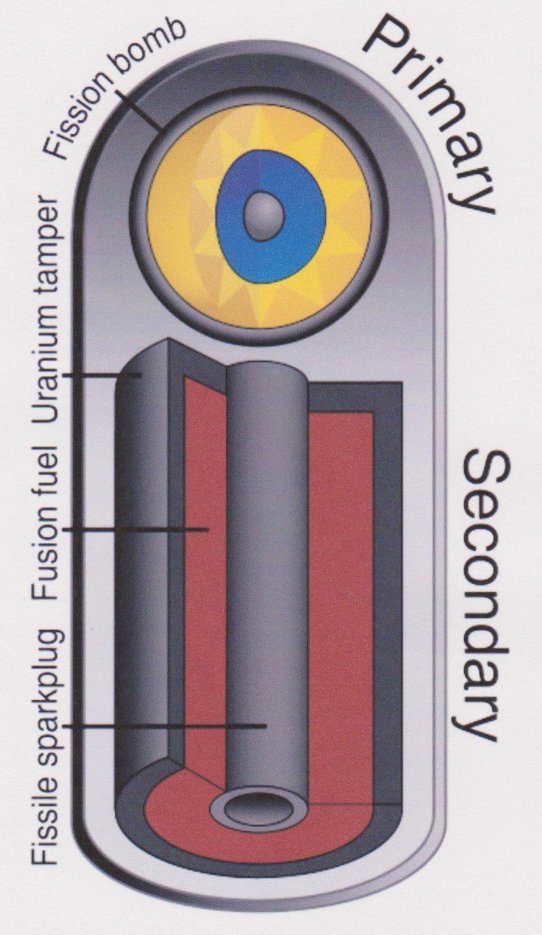

The Teller-Ulam design kept the fission and fusion fuel

physically separated from one another, and used X-rays

from the primary device "reflected" off the

surrounding

casing to compress the secondary.

In

an interview with Scientific American from 1999, Teller

told the reporter:

"I

contributed; Ulam did not. I'm sorry I had to answer it

in this abrupt way. Ulam was rightly dissatisfied with

an old approach. He came to me with a part of an idea

which I already had worked out and had difficulty getting

people to listen to. He was willing to sign a paper. When

it then came to defending that paper and really putting

work into it, he refused. He said, 'I don't believe in

it.'"

The

issue is controversial. Bethe considered Teller's contribution

to the invention of the H-bomb a true innovation as early

as 1952, and referred to his work as a "stroke of

genius" in 1954. In both cases, however, Bethe emphasized

Teller's role as a way of stressing that the development

of the H-bomb could not have been hastened by additional

support or funding, and Teller greatly disagreed with

Bethe's assessment. Other scientists (antagonistic to

Teller, such as J. Carson Mark) have claimed that Teller

would have never gotten any closer without the assistance

of Ulam and others. Ulam himself claimed that Teller only

produced a "more generalized" version of Ulam's

original design.

The

breakthrough—the details of which are still classified—was

apparently the separation of the fission and fusion components

of the weapons, and to use the X-rays produced by the

fission bomb to first compress the fusion fuel before

igniting it. Ulam's idea seems to have been to use mechanical

shock from the primary to encourage fusion in the secondary,

while Teller quickly realized that X-rays from the primary

would do the job much more symmetrically. Some members

of the laboratory (J. Carson Mark in particular) later

expressed the opinion that the idea to use the x-rays

would have eventually occurred to anyone working on the

physical processes involved, and that the obvious reason

why Teller thought of it right away was because he was

already working on the "Greenhouse" tests for

the spring of 1951, in which the effect of x-rays from

a fission bomb on a mixture of deuterium and tritium was

going to be investigated.

Whatever

the actual components of the so-called Teller–Ulam

design and the respective contributions of those who worked

on it, after it was proposed it was immediately seen by

the scientists working on the project as the answer which

had been so long sought. Those who previously had doubted

whether a fission-fusion bomb would be feasible at all

were converted into believing that it was only a matter

of time before both the USA and the USSR had developed

multi-megaton weapons. Even Oppenheimer, who was originally

opposed to the project, called the idea "technically

sweet."

Though

he had helped to come up with the design and had been

a long-time proponent of the concept, Teller was not chosen

to head the development project (his reputation of a thorny

personality likely played a role in this). In 1952, he

left Los Alamos and joined the newly established Livermore

branch of the University of California Radiation Laboratory,

which had been created largely through his urging. After

the detonation of "Ivy Mike", the first thermonuclear

weapon to utilize the Teller–Ulam configuration,

on November 1, 1952, Teller became known in the press

as the "father of the hydrogen bomb." Teller

himself refrained from attending the test—he claimed

not to feel welcome at the Pacific Proving Grounds—and

instead saw its results on a seismograph in the basement

of a hall in Berkeley.

The 10.4 Mt "Ivy Mike" shot of 1952 appeared

to vindicate

Teller's long-time advocacy for the hydrogen bomb.

There

was an opinion that by analyzing the fallout from this

test, the Soviets (led in their H-bomb work by Andrei

Sakharov) could have deciphered the new American design.

However, this was later denied by the Soviet bomb researchers.

Because of official secrecy, little information about

the bomb's development was released by the government,

and press reports often attributed the entire weapon's

design and development to Teller and his new Livermore

Laboratory (when it was actually developed by Los Alamos).

Many

of Teller's colleagues were irritated that he seemed to

enjoy taking full credit for something he had only a part

in, and in response, with encouragement from Enrico Fermi,

Teller authored an article titled "The Work of

Many People," which appeared in Science magazine

in February 1955, emphasizing that he was not alone in

the weapon's development. He would later write in his

memoirs that he had told a "white lie" in the

1955 article in order to "soothe ruffled feelings",

and claimed full credit for the invention.

Teller

was known for getting engrossed in projects which were

theoretically interesting but practically unfeasible (the

classic "Super" was one such project.)[17] About

his work on the hydrogen bomb, Bethe said:

"Nobody

will blame Teller because the calculations of 1946 were

wrong, especially because adequate computing machines

were not available at Los Alamos. But he was blamed at

Los Alamos for leading the laboratory, and indeed the

whole country, into an adventurous programme on the basis

of calculations, which he himself must have known to have

been very incomplete."

During

the Manhattan Project, Teller also advocated the development

of a bomb using uranium hydride, which many of his fellow

theorists said would be unlikely to work. At Livermore,

Teller continued work on the hydride bomb, and the result

was a dud. Ulam once wrote to a colleague about an idea

he had shared with Teller: "Edward is full of enthusiasm

about these possibilities; this is perhaps an indication

they will not work." Fermi once said that Teller

was the only monomaniac he knew who had several manias.

Carey

Sublette of Nuclear Weapon Archive argues that Ulam came

up with the radiation implosion compression design of

thermonuclear weapons, but that on the other hand Teller

has gotten little credit for being the first to propose

fusion boosting in 1945, which is essential for miniaturization

and reliability and is used in all of today's nuclear

weapons.

Oppenheimer

controversy

Teller

became controversial in 1954 when he testified against

J. Robert Oppenheimer, a former head of Los Alamos and

an advisor to the Atomic Energy Commission, at Oppenheimer's

security clearance hearing. Teller had clashed with Oppenheimer

many times at Los Alamos over issues relating both to

fission and fusion research, and during Oppenheimer's

trial he was the only member of the scientific community

to label Oppenheimer a security risk.

.jpg)

Teller testified about J. Robert Oppenheimer in 1954.

Asked

at the hearing by AEC attorney Roger Robb whether he was

planning "to suggest that Dr. Oppenheimer is disloyal

to the United States", Teller replied that:

I do not want to suggest anything of the kind. I know

Oppenheimer as an intellectually most alert and a very

complicated person, and I think it would be presumptuous

and wrong on my part if I would try in any way to analyze

his motives. But I have always assumed, and I now assume

that he is loyal to the United States. I believe this,

and I shall believe it until I see very conclusive proof

to the opposite.[39]

However,

he was immediately asked whether he believed that Oppenheimer

was a "security risk", to which he testified:

"In a great number of cases I have seen Dr. Oppenheimer

act — I understood that Dr. Oppenheimer acted —

in a way which for me was exceedingly hard to understand.

I thoroughly disagreed with him in numerous issues and

his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated.

To this extent, I feel that I would like to see the vital

interests of this country in hands which I understand

better, and therefore trust more. In this very limited

sense, I would like to express a feeling that I would

feel personally more secure if public matters would rest

in other hands."

Teller

also testified that Oppenheimer's opinion about the thermonuclear

program seemed to be based more on the scientific feasibility

of the weapon than anything else. He additionally testified

that Oppenheimer's direction of Los Alamos was "a

very outstanding achievement" both as a scientist

and an administrator, lauding his "very quick

mind" and that he made "just a most wonderful

and excellent director."

After

this, however, he detailed ways in which he felt that

Oppenheimer had hindered his efforts towards an active

thermonuclear development program, and at length criticized

Oppenheimer's decisions not to invest more work onto the

question at different points in his career, saying:

"If it is a question of wisdom and judgment, as

demonstrated by actions since 1945, then I would say one

would be wiser not to grant clearance."

Oppenheimer's

security clearance was revoked after the hearings. Most

of Teller's former colleagues disapproved of his testimony

and he became ostracized by much of the scientific community.

After the fact, Teller consistently denied that he was

intending to damn Oppenheimer, and even claimed that he

was attempting to exonerate him. Documentary evidence

has suggested that this was likely not the case, however.

Six days before the testimony, Teller met with an AEC

liaison officer and suggested "deepening the charges"

in his testimony. It has been suggested that Teller's

testimony against Oppenheimer was an attempt to remove

Oppenheimer from power so that Teller could become the

leader of the American nuclear scientist community.

Teller

always insisted that his testimony had not significantly

harmed Oppenheimer. In 2002, Teller contended that Oppenheimer

was "not destroyed" by the security hearing

but "no longer asked to assist in policy matters."

He claimed his words were an overreaction, because he

had only just learned of Oppenheimer's failure to immediately

report an approach by Haakon Chevalier, who had approached

Oppenheimer to help the Russians. Teller said that, in

hindsight, he would have responded differently.

Prior

to the Oppenheimer controversy, Teller maintained a friendly

relationship with Oppenheimer. When Leó Szilárd

asked Teller to help circulate a petition that discourages

the United States from using an atomic bomb on Japan unless

Japan is made fully aware of the possibility of such an

attack, he consulted Oppenheimer’s wisdom. Teller

believed that Oppenheimer was a natural leader and could

help him with such a formidable political problem. Oppenheimer

reassured Teller that the nation’s fate should be

left to the sensible politicians in Washington. Bolstered

by Oppenheimer’s influence, he decided to not sign

the petition. However, Teller learned soon after his meeting

that Oppenheimer conversely endorsed a political use of

the super bomb. Following Teller’s discovery, his

relationship with his advisor began to deteriorate.

US

Government work and political advocacy

After

the Oppenheimer controversy, Teller became ostracized

by much of the scientific community, but was still quite

welcome in the government and military science circles.

Along with his traditional advocacy for nuclear energy

development, a strong nuclear arsenal, and a vigorous

nuclear testing program, he had helped to develop nuclear

reactor safety standards as the chair of the Reactor Safeguard

Committee of the AEC in the late 1940s, and later headed

an effort at General Atomics which designed research reactors

in which a nuclear meltdown would be impossible (the TRIGA).

Teller

promoted increased defense spending to counter the perceived

Soviet missile threat. He was a signatory to the 1958

report by the military sub-panel of the Rockefeller Brothers

funded Special Studies Project, which called for a $3

billion annual increase in America's military budget.

He

was Director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

(1958–1960), which he helped to found (along with

Ernest O. Lawrence), and after that he continued as an

Associate Director. He chaired the committee that founded

the Space Sciences Laboratory at Berkeley. He also served

concurrently as a Professor of Physics at the University

of California, Berkeley. He was a tireless advocate of

a strong nuclear program and argued for continued testing

and development — in fact, he stepped down from the

directorship of Livermore so that he could better lobby

against the proposed test ban. He testified against the

test ban both before Congress as well as on television.

Teller on television (1960).

Teller

established the Department of Applied Science at the University

of California, Davis and LLNL in 1963, which holds the

Edward Teller endowed professorship in his honor. In 1975

he retired from both the lab and Berkeley, and was named

Director Emeritus of the Livermore Laboratory and appointed

Senior Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution. In 1983,

he spoke at The Thomas Jefferson School, a conference

of intellectuals discussing Objectivism organized by economist

Professor George Reisman, where he received a standing

ovation. After the fall of communism in Hungary in 1989,

he made several visits to his country of origin, and paid

careful attention to the political changes there.

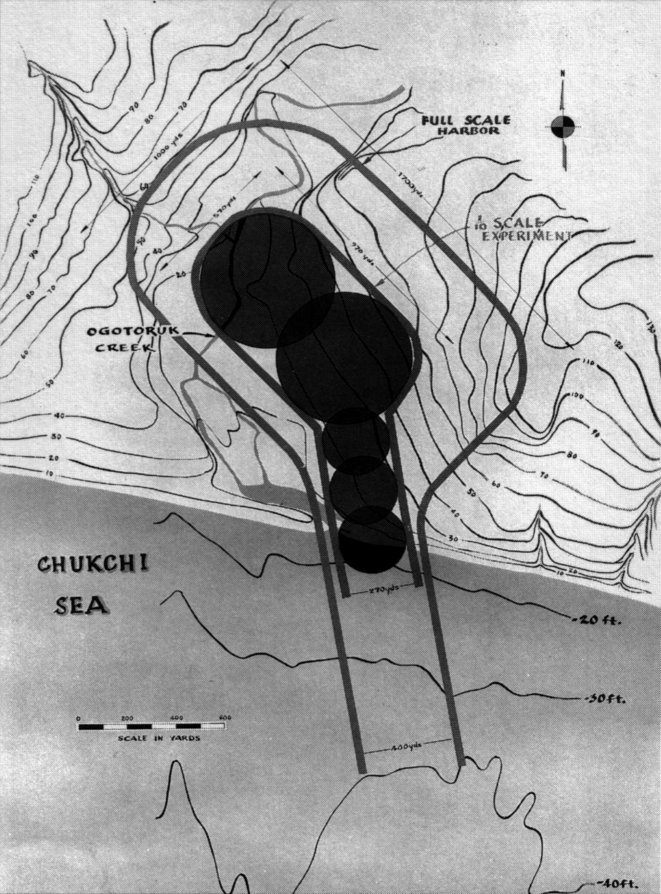

Operation Plowshare and Project Chariot

Teller

was one of the strongest and best-known advocates for

investigating non-military uses of nuclear explosives,

which the United States explored under Operation Plowshare.

One of the most controversial projects he proposed was

a plan to use a multi-megaton hydrogen bomb to dig a deep-water

harbor more than a mile long and half a mile wide to use

for shipment of resources from coal and oil fields through

Point Hope, Alaska. The Atomic Energy Commission accepted

Teller's proposal in 1958 and it was designated Project

Chariot. While the AEC was scouting out the Alaskan site,

and having withdrawn the land from the public domain,

Teller publicly advocated the economic benefits of the

plan, but was unable to convince local government leaders

that the plan was financially viable.

One of the Chariot schemes involved chaining five

thermonuclear devices to create the artificial harbor.

Other

scientists criticized the project as being potentially

unsafe for the local wildlife and the Inupiat people living

near the designated area, who were not officially told

of the plan until March 1960.[50] Additionally, it turned

out that the harbor would be ice-bound for nine months

out of the year. In the end, due to the financial infeasibility

of the project and the concerns over radiation-related

health issues, the project was cancelled in 1962.

A

related experiment which also had Teller's endorsement

was a plan to extract oil from the tar sands in northern

Alberta with nuclear explosions. The plan actually received

the endorsement of the Alberta government, but was rejected

by the Government of Canada under Prime Minister John

Diefenbaker, who was opposed to having any nuclear weapons

in Canada, although Canada had nuclear weapons from 1963

to 1984.

Nuclear

technology and Israel

For

some twenty years, Teller advised Israel on nuclear matters

in general, and on the building of a hydrogen bomb in

particular. In 1952, Teller and Oppenheimer had a long

meeting with David Ben-Gurion in Tel Aviv, telling him

that the best way to accumulate plutonium was to burn

natural uranium in a nuclear reactor. Starting in 1964,

a connection between Teller and Israel was made by the

physicist Yuval Neeman, who had similar political views.

Between 1964 and 1967, Teller visited Israel six times,

lecturing at Tel Aviv University, and advising the chiefs

of Israel's scientific-security circle as well as prime

ministers and cabinet members.

At

each of his talks with members of the Israeli security

establishment's highest levels he would make them swear

that they would never be tempted into signing the Nuclear

Non-Proliferation Treaty. In 1967, when the Israeli nuclear

program was nearing completion, Teller informed Neeman

that he was going to tell the CIA that Israel had built

nuclear weapons and explain that it was justified by the

background of the Six-Day War. After Neeman cleared it

with Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, Teller briefed the head

of the CIA's Office of Science and Technology, Carl Duckett.

It took a year for Teller to convince the CIA that Israel

had obtained nuclear capability; the information then

went through CIA Director Richard Helms and then to the

US president at that time, Lyndon B. Johnson. Teller also

persuaded them to end the American attempts to inspect

the Negev Nuclear Research Center in Dimona. Teller's

personal opinion became factual assertion, when in 1976

Carl Duckett testified in Congress before the Nuclear

Regulatory Commission, that after receiving information

from "American scientist", he drafted a National

Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on Israel's nuclear capability.

In

the 1980s, Teller again visited Israel to advise the Israeli

government on building a nuclear reactor. Three decades

later, Teller confirmed that it was during his visits

that he concluded that Israel was in possession of nuclear

weapons. After conveying the matter to the U.S. government,

Teller reportedly said: "They [Israeli] have it,

and they were clever enough to trust their research and

not to test, they know that to test would get them into

trouble."

Three

Mile Island

Teller

suffered a heart attack in 1979, and many observers described

him as blaming it on Jane Fonda: She had starred in The

China Syndrome, which depicted a fictional reactor accident

and was released less than two weeks before the Three

Mile Island accident. She outspokenly lobbied against

nuclear power while promoting the film. Teller acted quickly

to lobby in favor of nuclear energy, testifying to its

safety and reliability, and soon after one flurry of activity

suffered the attack. He signed a two-page-spread ad in

the July 31, 1979, Wall Street Journal with the headline

"I was the only victim of Three-Mile Island".

It opened with:

"On

May 7, a few weeks after the accident at Three-Mile Island,

I was in Washington. I was there to refute some of that

propaganda that Ralph Nader, Jane Fonda and their kind

are spewing to the news media in their attempt to frighten

people away from nuclear power. I am 71 years old, and

I was working 20 hours a day. The strain was too much.

The next day, I suffered a heart attack. You might say

that I was the only one whose health was affected by that

reactor near Harrisburg. No, that would be wrong. It was

not the reactor. It was Jane Fonda. Reactors are not dangerous."

The

next day, The New York Times ran an editorial criticizing

the ad, noting that it was sponsored by Dresser Industries,

the firm that had manufactured one of the defective valves

that contributed to the Three Mile Island accident.

Strategic

Defense Initiative

In

the 1980s, Teller began a strong campaign for what was

later called the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), derided

by critics as "Star Wars," the concept of using

ground and satellite-based lasers, particle beams and

missiles to destroy incoming Soviet ICBMs. Teller lobbied

with government agencies—and got the approval of

President Ronald Reagan — for a plan to develop a

system using elaborate satellites which used atomic weapons

to fire X-ray lasers at incoming missiles — as part

of a broader scientific research program into defenses

against nuclear weapons. Scandal erupted when Teller (and

his associate Lowell Wood) were accused of deliberately

overselling the program and perhaps had encouraged the

dismissal of a laboratory director (Roy Woodruff) who

had attempted to correct the error. His claims led to

a joke which circulated in the scientific community, that

a new unit of unfounded optimism was designated as the

teller; one teller was so large that most events had to

be measured in nanotellers or picotellers. Many prominent

scientists argued that the system was futile. Bethe, along

with IBM physicist Richard Garwin and Cornell University

colleague Kurt Gottfried, wrote an article in Scientific

American which analyzed the system and concluded that

any putative enemy could disable such a system by the

use of suitable decoys. The project's funding was eventually

scaled back.

Teller became a major lobbying force of the Strategic

Defense

Initiative to President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s.

Many

scientists opposed strategic defense on moral or political

rather than purely technical grounds. They argued that,

even if an effective system could be produced, it would

undermine the system of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD)

that had prevented all-out war between the western democracies

and the communist bloc. An effective defense, they contended,

would make such a war "winnable" and therefore

more likely.

Despite

(or perhaps because of) his hawkish reputation, Teller

made a public point of noting that he regretted the use

of the first atomic bombs on civilian cities during World

War II. He further claimed that before the bombing of

Hiroshima he had indeed lobbied Oppenheimer to use the

weapons first in a "demonstration" which could

be witnessed by the Japanese high-command and citizenry

before using them to inflict thousands of deaths. The

"father of the hydrogen bomb" would use this

quasi-anti-nuclear stance (he would say that he believed

nuclear weapons to be unfortunate, but that the arms race

was unavoidable due to the intractable nature of Communism)

to promote technologies such as SDI, arguing that they

were needed to make sure that nuclear weapons could never

be used again (Better a shield than a sword was the title

of one of his books on the subject).

There

is contrary evidence. In the 1970s, a letter of Teller

to Leó Szilárd emerged, dated July 2, 1945:

"Our

only hope is in getting the facts of our results before

the people. This might help convince everybody the next

war would be fatal. For this purpose, actual combat-use

might even be the best thing."

The

historian Barton Bernstein argued that it is an "unconvincing

claim" by Teller that he was a "covert dissenter"

to the use of the weapon. In his 2001 Memoirs, Teller

claims that he did lobby Oppenheimer, but that Oppenheimer

had convinced him that he should take no action and that

the scientists should leave military questions in the

hands of the military; Teller claims he was not aware

that Oppenheimer and other scientists were being consulted

as to the actual use of the weapon and implies that Oppenheimer

was being hypocritical.

Teller's

own comments on the role of lasers in SDI, as disclosed

in live panel discussions, were published, and are available,

in two laser conference proceedings.

Legacy

In

his early career, Teller made contributions to nuclear

and molecular physics, spectroscopy (the Jahn–Teller

and Renner–Teller effects), and surface physics.

His extension of Fermi's theory of beta decay (in the

form of the so-called Gamow–Teller transitions) provided

an important stepping stone in the applications of this

theory. The Jahn–Teller effect and the BET theory

have retained their original formulation and are still

mainstays in physics and chemistry. Teller also made contributions

to Thomas–Fermi theory, the precursor of density

functional theory, a standard modern tool in the quantum

mechanical treatment of complex molecules. In 1953, along

with Nicholas Metropolis and Marshall Rosenbluth, Teller

co-authored a paper which is a standard starting point

for the applications of the Monte Carlo method to statistical

mechanics.

.jpg)

Edward Teller in his later years

Teller's

vigorous advocacy for strength through nuclear weapons,

especially when so many of his wartime colleagues later

expressed regret about the arms race, made him an easy

target for the "mad scientist" stereotype.

In 1991, he was awarded one of the first Ig Nobel Prizes

for Peace in recognition of his "lifelong efforts

to change the meaning of peace as we know it". He

was also rumored to be one of the inspirations for the

character of Dr. Strangelove in Stanley Kubrick's 1964

satirical film of the same name (others speculated to

be RAND theorist Herman Kahn, rocket scientist Wernher

von Braun, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara).

In the aforementioned Scientific American interview from

1999, he was reported as having bristled at the question:

"My name is not Strangelove. I don't know about

Strangelove. I'm not interested in Strangelove. What else

can I say?... Look. Say it three times more, and I throw

you out of this office." Nobel Prize winning

physicist Isidor I. Rabi once suggested that "It

would have been a better world without Teller."

In addition, Teller's false claims that Stanislaw Ulam

made no significant contribution to the development of

the hydrogen bomb (despite Ulam's key insights of using

compression and staging elements to generate the thermonuclear

reaction) and his personal attacks on Oppenheimer caused

even greater animosity within the general physics community

towards Teller.

Appearing on television discussion After Dark in 1987

In

1986, he was awarded the United States Military Academy's

Sylvanus Thayer Award. He was a fellow of the American

Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Association

for the Advancement of Science, and the American Nuclear

Society. Among the honors he received were the Albert

Einstein Award, the Enrico Fermi Award, the Corvin Chain

and the National Medal of Science. He was also named as

part of the group of "U.S. Scientists" who were

Time magazine's People of the Year in 1960, and an asteroid,

5006 Teller, is named after him.[69] He was awarded with

the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George

W. Bush less than two months before his death. His final

paper, published posthumously, advocated the construction

of a prototype liquid fluoride thorium reactor.

Teller

died in Stanford, California on September 9, 2003, at

the age of 95.

Sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Teller

https://www.llnl.gov/str/October03/Teller.html