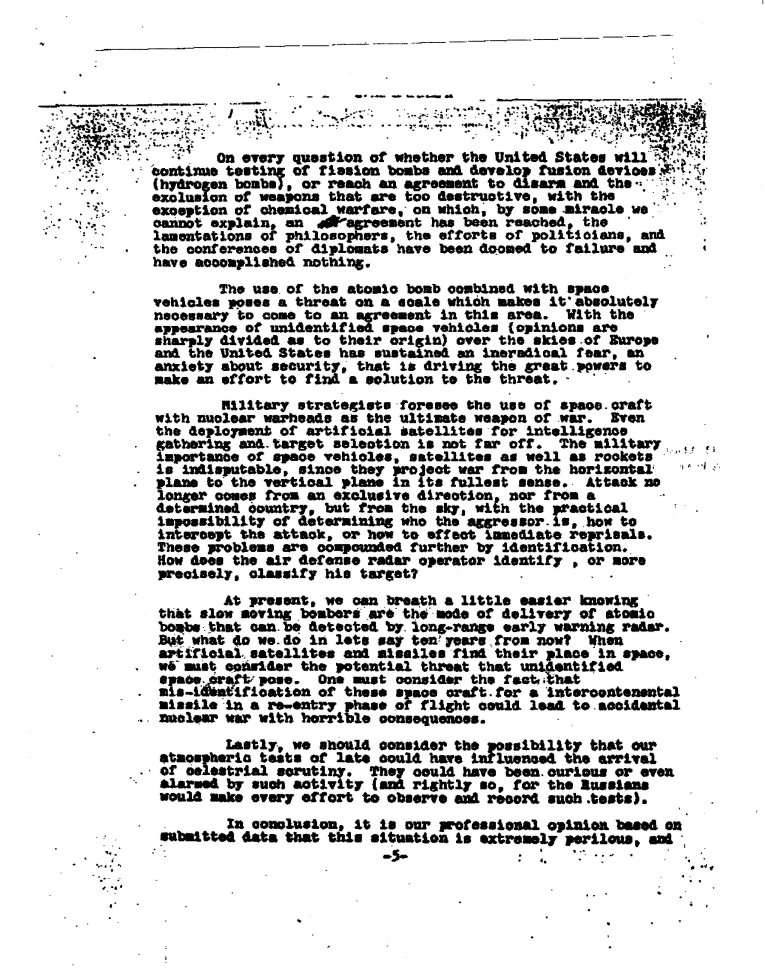

Julius

Robert Oppenheimer (April 22, 1904 – February 18,

1967) was an American theoretical physicist and professor

of physics at the University of California, Berkeley.

Along with Enrico Fermi, he is often called the "father

of the atomic bomb" for his role in the Manhattan

Project, the World War II project that developed the first

nuclear weapons. The first atomic bomb was detonated on

July 16, 1945, in the Trinity test in New Mexico; Oppenheimer

remarked later that it brought to mind words from the

Bhagavad Gita: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer

of worlds."

J.

Robert Oppenheimer, c. 1944

After

the war, he became a chief advisor to the newly created

United States Atomic Energy Commission and used that position

to lobby for international control of nuclear power to

avert nuclear proliferation and an arms race with the

Soviet Union. After provoking the ire of many politicians

with his outspoken opinions during the Second Red Scare,

he had his security clearance revoked in a much-publicized

hearing in 1954, and was effectively stripped of his direct

political influence; he continued to lecture, write and

work in physics. A decade later, President John F. Kennedy

awarded (and Lyndon B. Johnson presented) him with the

Enrico Fermi Award as a gesture of political rehabilitation.

Oppenheimer's

notable achievements in physics include the Born–Oppenheimer

approximation for molecular wavefunctions, work on the

theory of electrons and positrons, the Oppenheimer–Phillips

process in nuclear fusion, and the first prediction of

quantum tunneling. With his students, he also made important

contributions to the modern theory of neutron stars and

black holes, as well as to quantum mechanics, quantum

field theory, and the interactions of cosmic rays. As

a teacher and promoter of science, he is remembered as

a founding father of the American school of theoretical

physics that gained world prominence in the 1930s. After

World War II, he became director of the Institute for

Advanced Study in Princeton.

Early

life

Childhood

and education

Oppenheimer

was born in New York City on April 22, 1904, to Julius

Oppenheimer, a wealthy Jewish textile importer who had

immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1888,

and Ella Friedman, a painter. In 1912, the family moved

to an apartment on the eleventh floor of 155 Riverside

Drive, near West 88th Street, Manhattan, an area known

for luxurious mansions and town houses. Their art collection

included works by Pablo Picasso and Édouard Vuillard,

and at least three original paintings by Vincent van Gogh.

Robert had a younger brother, Frank, who also became a

physicist.

Oppenheimer

was initially schooled at Alcuin Preparatory School, and

in 1911, entered the Ethical Culture Society School. This

had been founded by Felix Adler to promote a form of ethical

training based on the Ethical Culture movement, whose

motto was "Deed before Creed". His father had

been a member of the Society for many years, serving on

its board of trustees from 1907 to 1915. Oppenheimer was

a versatile scholar, interested in English and French

literature, and particularly in mineralogy. He completed

the third and fourth grades in one year, and skipped half

the eighth grade. During his final year, he became interested

in chemistry. He entered Harvard College a year late,

at age 18, because he suffered an attack of colitis while

prospecting in Joachimstal during a family summer vacation

in Europe. To help him recover from the illness, his father

enlisted the help of his English teacher Herbert Smith

who took him to New Mexico, where Oppenheimer fell in

love with horseback riding and the southwestern United

States.

In

addition to majoring in chemistry, he was also required

by Harvard's rules to study history, literature, and philosophy

or mathematics. He made up for his late start by taking

six courses each term and was admitted to the undergraduate

honor society Phi Beta Kappa. In his first year, he was

admitted to graduate standing in physics on the basis

of independent study, which meant he was not required

to take the basic classes and could enroll instead in

advanced ones. A course on thermodynamics taught by Percy

Bridgman attracted him to experimental physics. He graduated

summa cum laude in three years.

Studies

in Europe

In

1924, Oppenheimer was informed that he had been accepted

into Christ's College, Cambridge. He wrote to Ernest Rutherford

requesting permission to work at the Cavendish Laboratory.

Bridgman provided Oppenheimer with a recommendation, which

conceded that Oppenheimer's clumsiness in the laboratory

made it apparent his forte was not experimental but rather

theoretical physics. Rutherford was unimpressed, but Oppenheimer

went to Cambridge in the hope of landing another offer.

He was ultimately accepted by J. J. Thomson on condition

that he complete a basic laboratory course. He developed

an antagonistic relationship with his tutor, Patrick Blackett,

who was only a few years his senior. While on vacation,

as recalled by his friend Francis Ferguson, Oppenheimer

once confessed that he had left an apple doused with noxious

chemicals on Blackett's desk. While Ferguson's account

is the only detailed version of this event, Oppenheimer's

parents were alerted by the university authorities who

considered placing him on probation, a fate prevented

by his parents successfully lobbying the authorities.

A

tall, thin chain smoker, who often neglected to eat during

periods of intense thought and concentration, Oppenheimer

was marked by many of his friends as having self-destructive

tendencies. A disturbing event occurred when he took a

vacation from his studies in Cambridge to meet up with

his friend Francis Fergusson in Paris. Fergusson noticed

that Oppenheimer was not well and to help distract him

from his depression told Oppenheimer that he (Fergusson)

was to marry his girlfriend Frances Keeley. Robert did

not take the news well. He jumped on Fergusson and tried

to strangle him. Although Ferguson easily fended off the

attack, the episode convinced him of Oppenheimer's deep

psychological troubles. Plagued throughout his life by

periods of depression, Oppenheimer once told his brother,

"I need physics more than friends".

In

1926, he left Cambridge for the University of Göttingen

to study under Max Born. Göttingen was one of the

world's leading centers for theoretical physics. Oppenheimer

made friends who went on to great success, including Werner

Heisenberg, Pascual Jordan, Wolfgang Pauli, Paul Dirac,

Enrico Fermi and Edward Teller. He was known for being

too enthusiastic in discussion, sometimes to the point

of taking over seminar sessions. This irritated some of

Born's other students so much that Maria Goeppert presented

Born with a petition signed by herself and others threatening

a boycott of the class unless he made Oppenheimer quiet

down. Born left it out on his desk where Oppenheimer could

read it, and it was effective without a word being said.

Heike

Kamerlingh Onnes' Laboratory in Leiden, Netherlands, 1926.

Oppenheimer is in the second row, third from the left.

He

obtained his Doctor of Philosophy degree in March 1927

at age 23, supervised by Born. After the oral exam, James

Franck, the professor administering, reportedly said,

"I'm glad that's over. He was on the point of

questioning me." Oppenheimer published more than

a dozen papers at Göttingen, including many important

contributions to the new field of quantum mechanics. He

and Born published a famous paper on the Born-Oppenheimer

approximation, which separates nuclear motion from electronic

motion in the mathematical treatment of molecules, allowing

nuclear motion to be neglected to simplify calculations.

It remains his most cited work.

Early

professional work

Educational

work

Oppenheimer

was awarded a United States National Research Council

fellowship to the California Institute of Technology (Caltech)

in September 1927. Bridgman also wanted him at Harvard,

so a compromise was reached whereby he split his fellowship

for the 1927–28 academic year between Harvard in

1927 and Caltech in 1928. At Caltech, he struck up a close

friendship with Linus Pauling, and they planned to mount

a joint attack on the nature of the chemical bond, a field

in which Pauling was a pioneer, with Oppenheimer supplying

the mathematics and Pauling interpreting the results.

Both the collaboration and their friendship were nipped

in the bud when Pauling began to suspect Oppenheimer of

becoming too close to his wife, Ava Helen Pauling. Once,

when Pauling was at work, Oppenheimer had arrived at their

home and invited Ava Helen to join him on a tryst in Mexico,

though she refused and reported the incident to her husband.

The invitation, and her apparent nonchalance about it,

disquieted Pauling, and he ended his relationship with

Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer later invited him to become head

of the Chemistry Division of the Manhattan Project, but

Pauling refused, saying he was a pacifist.

In

the autumn of 1928, Oppenheimer visited Paul Ehrenfest's

institute at the University of Leiden, the Netherlands,

where he impressed them by giving lectures in Dutch, despite

having little experience with the language. There, he

was given the nickname of Opje, later anglicized by his

students as "Oppie". From Leiden, he continued

on to the ETH in Zurich to work with Wolfgang Pauli on

quantum mechanics and the continuous spectrum. Oppenheimer

respected and liked Pauli and may have emulated his personal

style as well as his critical approach to problems.

On

returning to the United States, Oppenheimer accepted an

associate professorship from the University of California,

Berkeley, where Raymond T. Birge wanted him so badly that

he expressed a willingness to share him with Caltech.

The

University of California, Berkeley, where Oppenheimer

taught from 1929 to 1943

Before

his Berkeley professorship began, Oppenheimer was diagnosed

with a mild case of tuberculosis and, with his brother

Frank, spent some weeks at a ranch in New Mexico, which

he leased and eventually purchased. When he heard the

ranch was available for lease, he exclaimed, "Hot

dog!", and later called it Perro Caliente, literally

"hot dog" in Spanish. Later, he used to say

that "physics and desert country" were his "two

great loves". He recovered from the tuberculosis

and returned to Berkeley, where he prospered as an adviser

and collaborator to a generation of physicists who admired

him for his intellectual virtuosity and broad interests.

His students and colleagues saw him as mesmerizing: hypnotic

in private interaction, but often frigid in more public

settings. His associates fell into two camps: one that

saw him as an aloof and impressive genius and aesthete,

the other that saw him as a pretentious and insecure poseur.

His students almost always fell into the former category,

adopting his walk, speech, and other mannerisms, and even

his inclination for reading entire texts in their original

languages. Hans Bethe said of him:

Probably the most important ingredient he brought to

his teaching was his exquisite taste. He always knew what

were the important problems, as shown by his choice of

subjects. He truly lived with those problems, struggling

for a solution, and he communicated his concern to the

group. In its heyday, there were about eight or ten graduate

students in his group and about six Post-doctoral Fellows.

He met this group once a day in his office, and discussed

with one after another the status of the student’s

research problem. He was interested in everything, and

in one afternoon they might discuss quantum electrodynamics,

cosmic rays, electron pair production and nuclear physics.

He

worked closely with Nobel Prize-winning experimental physicist

Ernest O. Lawrence and his cyclotron pioneers, helping

them understand the data their machines were producing

at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. In 1936,

Berkeley promoted him to full professor at a salary of

$3300 per annum. In return, he was asked to curtail his

teaching at Caltech, so a compromise was reached whereby

Berkeley released him for six weeks each year, enough

to teach one term at Caltech.

Scientific

work

Oppenheimer

did important research in theoretical astronomy (especially

as related to general relativity and nuclear theory),

nuclear physics, spectroscopy, and quantum field theory,

including its extension into quantum electrodynamics.

The formal mathematics of relativistic quantum mechanics

also attracted his attention, although he doubted its

validity. His work predicted many later finds, which include

the neutron, meson and neutron star.

Initially,

his major interest was the theory of the continuous spectrum

and his first published paper, in 1926, concerned the

quantum theory of molecular band spectra. He developed

a method to carry out calculations of its transition probabilities.

He calculated the photoelectric effect for hydrogen and

X-rays, obtaining the absorption coefficient at the K-edge.

His calculations accorded with observations of the X-ray

absorption of the sun, but not hydrogen. Years later,

it was realized that the sun was largely composed of hydrogen

and that his calculations were indeed correct.

Oppenheimer

with Albert Einstein.

Oppenheimer

also made important contributions to the theory of cosmic

ray showers and started work that eventually led to descriptions

of quantum tunneling. In 1931, he co-wrote a paper on

the "Relativistic Theory of the Photoelectric Effect"

with his student Harvey Hall, in which, based on empirical

evidence, he correctly disputed Dirac's assertion that

two of the energy levels of the hydrogen atom have the

same energy. Subsequently, one of his doctoral students,

Willis Lamb, determined that this was a consequence of

what became known as the Lamb shift, for which Lamb was

awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1955.

Oppenheimer

worked with his first doctoral student, Melba Phillips,

on calculations of artificial radioactivity under bombardment

by deuterons. When Ernest Lawrence and Edwin McMillan

bombarded nuclei with deuterons they found the results

agreed closely with the predictions of George Gamow, but

when higher energies and heavier nuclei were involved,

the results did not conform to the theory. In 1935, Oppenheimer

and Phillips worked out a theory now known as the Oppenheimer-Phillips

process to explain the results, a theory still in use

today.

As

early as 1930, Oppenheimer wrote a paper essentially predicting

the existence of the positron, after a paper by Paul Dirac

proposed that electrons could have both a positive charge

and negative energy. Dirac's paper introduced an equation,

known as the Dirac equation, which unified quantum mechanics,

special relativity and the then-new concept of electron

spin, to explain the Zeeman effect. Oppenheimer, drawing

on the body of experimental evidence, rejected the idea

that the predicted positively charged electrons were protons.

He argued that they would have to have the same mass as

an electron, whereas experiments showed that protons were

much heavier than electrons. Two years later, Carl David

Anderson discovered the positron, for which he received

the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physics.

In

the late 1930s Oppenheimer became interested in astrophysics,

probably through his friendship with Richard Tolman, resulting

in a series of papers. In the first of these, a 1938 paper

co-written with Robert Serber entitled "On the Stability

of Stellar Neutron Cores", Oppenheimer explored the

properties of white dwarfs. This was followed by a paper

co-written with one of his students, George Volkoff, "On

Massive Neutron Cores", in which they demonstrated

that there was a limit, the so-called Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff

limit, to the mass of stars beyond which they would not

remain stable as neutron stars and would undergo gravitational

collapse. Finally, in 1939, Oppenheimer and another of

his students, Hartland Snyder, produced a paper "On

Continued Gravitational Attraction", which predicted

the existence of what are today known as black holes.

After the Born-Oppenheimer approximation paper, these

papers remain his most cited, and were key factors in

the rejuvenation of astrophysical research in the United

States in the 1950s, mainly by John A. Wheeler.

Oppenheimer's

papers were considered difficult to understand even by

the standards of the abstract topics he was expert in.

He was fond of using elegant, if extremely complex, mathematical

techniques to demonstrate physical principles, though

he was sometimes criticized for making mathematical mistakes,

presumably out of haste. "His physics was good",

said his student Snyder, "but his arithmetic awful."

Oppenheimer

published only five scientific papers, one of which was

in biophysics, after World War II, and none after 1950.

Murray Gell-Mann, a later Nobelist who, as a visiting

scientist, worked with him at the Institute for Advanced

Study in 1951, offered this opinion:

He didn't have Sitzfleisch, 'sitting flesh,' when you

sit on a chair. As far as I know, he never wrote a long

paper or did a long calculation, anything of that kind.

He didn't have patience for that; his own work consisted

of little aperçus, but quite brilliant ones. But

he inspired other people to do things, and his influence

was fantastic.

Oppenheimer's

diverse interests sometimes interrupted his focus on projects.

In 1933, he learned Sanskrit and met the Indologist Arthur

W. Ryder at Berkeley. He read the Bhagavad Gita in the

original Sanskrit and later, he cited it as one of the

books that most shaped his philosophy of life. His close

confidant and colleague, Nobel Prize winner Isidor Rabi,

later gave his own interpretation:

Oppenheimer was overeducated in those fields, which lie

outside the scientific tradition, such as his interest

in religion, in the Hindu religion in particular, which

resulted in a feeling of mystery of the universe that

surrounded him like a fog. He saw physics clearly, looking

toward what had already been done, but at the border,

he tended to feel there was much more of the mysterious

and novel than there actually was ... [he turned] away

from the hard, crude methods of theoretical physics into

a mystical realm of broad intuition.

In

spite of this, observers such as Nobel Prize-winning physicist

Luis Alvarez have suggested that if he had lived long

enough to see his predictions substantiated by experiment,

Oppenheimer might have won a Nobel Prize for his work

on gravitational collapse, concerning neutron stars and

black holes. In retrospect, some physicists and historians

consider this to be his most important contribution, though

it was not taken up by other scientists in his own lifetime.

The physicist and historian Abraham Pais once asked Oppenheimer

what he considered to be his most important scientific

contributions; Oppenheimer cited his work on electrons

and positrons, not his work on gravitational contraction.

Oppenheimer was nominated for the Nobel Prize for physics

three times, in 1945, 1951 and 1967, but never won.

Private

and political life

During

the 1920s, Oppenheimer remained aloof from worldly matters.

He claimed that he did not read newspapers or listen to

the radio, and had only learned of the Wall Street crash

of 1929 some six months after it occurred while on a walk

with Ernest Lawrence. He once remarked that he never cast

a vote until the 1936 election. However, from 1934 on,

he became increasingly concerned about politics and international

affairs. In 1934, he earmarked three percent of his salary—about

$100 a year—for two years to support German physicists

fleeing from Nazi Germany. During the 1934 West Coast

Waterfront Strike, he and some of his students, including

Melba Phillips and Bob Serber, attended a longshoremen's

rally. Oppenheimer repeatedly attempted to get Serber

a position at Berkeley but was blocked by Birge, who felt

that "one Jew in the department was enough".

Oppenheimer's

mother died in 1931, and he became closer to his father

who, although still living in New York, became a frequent

visitor in California. When his father died in 1937 leaving

$392,602 to be divided between Oppenheimer and his brother

Frank, Oppenheimer immediately wrote out a will leaving

his estate to the University of California for graduate

scholarships. Like many young intellectuals in the 1930s,

he was a supporter of social reforms that were later alleged

to be communist ideas. He donated to many progressive

efforts which were later branded as "left-wing"

during the McCarthy era. The majority of his allegedly

radical work consisted of hosting fund raisers for the

Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War and other anti-fascist

activity. He never openly joined the Communist Party,

though he did pass money to liberal causes by way of acquaintances

who were alleged to be Party members. In 1936, Oppenheimer

became involved with Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a Berkeley

literature professor and a student at Stanford University

School of Medicine. The two had similar political views;

she wrote for the Western Worker, a Communist Party newspaper.

Oppenheimer

broke up with Tatlock in 1939. In August that year, he

met Katherine ("Kitty") Puening Harrison, a

radical Berkeley student and former Communist Party member.

Harrison had been married three times previously. Her

first marriage lasted only a few months. Her second husband

was Joe Dallet, an active member of the Communist party,

who was killed in the Spanish Civil War. Kitty returned

to the United States where she obtained a Bachelor of

Arts degree in botany from the University of Pennsylvania.

There she married Richard Harrison, a physician and medical

researcher, in 1938. In June 1939, Kitty and Harrison

moved to Pasadena, California, where he became chief of

radiology at a local hospital and she enrolled as a graduate

student at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Oppenheimer and Kitty created a minor scandal by sleeping

together after one of Tolman's parties. In the summer

of 1940, she stayed with Oppenheimer at his ranch in New

Mexico. She finally asked Harrison for a divorce when

she found out she was pregnant. When he refused, she obtained

an instant divorce in Reno, Nevada, and married Oppenheimer

on November 1, 1940.

Their

first child Peter was born in May 1941, and their second

child, Katherine ("Toni"), was born in Los Alamos,

New Mexico, on December 7, 1944. During his marriage,

Oppenheimer continued his affair with Jean Tatlock. Later,

their continued contact became an issue in his security

clearance hearings because of Tatlock's Communist associations.

Many of Oppenheimer's closest associates were active in

the Communist Party in the 1930s or 1940s. They included

his brother Frank, Frank's wife Jackie, Kitty, Jean Tatlock,

his landlady Mary Ellen Washburn, and several of his graduate

students at Berkeley.

When

he joined the Manhattan Project in 1942, Oppenheimer wrote

on his personal security questionnaire that he [Oppenheimer]

had been "a member of just about every Communist

Front organization on the West Coast". Years later,

he claimed that he did not remember saying this, that

it was not true, and that if he had said anything along

those lines, it was "a half-jocular overstatement".

He was a subscriber to the People's World, a Communist

Party organ, and he testified in 1954, "I was

associated with the Communist movement." From

1937 to 1942, in the midst of the Great Purge and Hitler-Stalin

pact, Oppenheimer was a member at Berkeley of what he

called a "discussion group", which was later

identified by fellow members, Haakon Chevalier and Gordon

Griffiths, as a "closed" (secret) unit of the

Communist Party for Berkeley faculty.

Oppenheimer's

badge photo from Los Alamos

The

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) recorded that J.

Robert Oppenheimer attended a meeting in the home of self-proclaimed

Communist Haakon Chevalier, that the Communist Party's

California state chairman William Schneiderman, and Isaac

Folkoff, West Coast liaison between the Communist Party

and NKVD, attended in Fall 1940, during the Hitler-Stalin

pact. Shortly thereafter, the FBI added Oppenheimer to

its Custodial Detention Index, for arrest in case of national

emergency, and listed him as "Nationalistic Tendency:

Communist". Debates over Oppenheimer's Party membership

or lack thereof have turned on very fine points; almost

all historians agree he had strong left-wing sympathies

during this time and interacted with Party members, though

there is considerable dispute over whether he was officially

a member of the Party. At his 1954 security clearance

hearings, he denied being a member of the Communist Party,

but identified himself as a fellow traveler, which he

defined as someone who agrees with many of the goals of

Communism, but without being willing to blindly follow

orders from any Communist party apparatus.

Throughout

the development of the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer was under

investigation by both the FBI and the Manhattan Project's

internal security arm for his past left-wing associations.

He was followed by Army security agents during a trip

to California in June 1943 to visit his former girlfriend,

Jean Tatlock, who was suffering from depression. Oppenheimer

spent the night in her apartment. Tatlock committed suicide

on January 4, 1944, which left Oppenheimer deeply grieved.

In August 1943, he volunteered to Manhattan Project security

agents that George Eltenton, whom he did not know, had

solicited three men at Los Alamos for nuclear secrets

on behalf of the Soviet Union. When pressed on the issue

in later interviews, Oppenheimer admitted that the only

person who had approached him was his friend Haakon Chevalier,

a Berkeley professor of French literature, who had mentioned

the matter privately at a dinner at Oppenheimer's house.

Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, Jr., the director

of the Manhattan Project, thought Oppenheimer was too

important to the project to be ousted over this suspicious

behavior. On July 20, 1943, he wrote to the Manhattan

Engineer District:

In accordance with my verbal directions of July 15,

it is desired that clearance be issued to Julius Robert

Oppenheimer without delay irrespective of the information

which you have concerning Mr Oppenheimer. He is absolutely

essential to the project.

Manhattan

Project

Los

Alamos

On

October 9, 1941, shortly before the United States entered

World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved

a crash program to develop an atomic bomb. In May 1942,

National Defense Research Committee Chairman James B.

Conant, who had been one of Oppenheimer's lecturers at

Harvard, invited Oppenheimer to take over work on fast

neutron calculations, a task that Oppenheimer threw himself

into with full vigor. He was given the title "Coordinator

of Rapid Rupture", specifically referring to the

propagation of a fast neutron chain reaction in an atomic

bomb. One of his first acts was to host a summer school

for bomb theory at his building in Berkeley. The mix of

European physicists and his own students — a group

including Robert Serber, Emil Konopinski, Felix Bloch,

Hans Bethe and Edward Teller — busied themselves

calculating what needed to be done, and in what order,

to make the bomb.

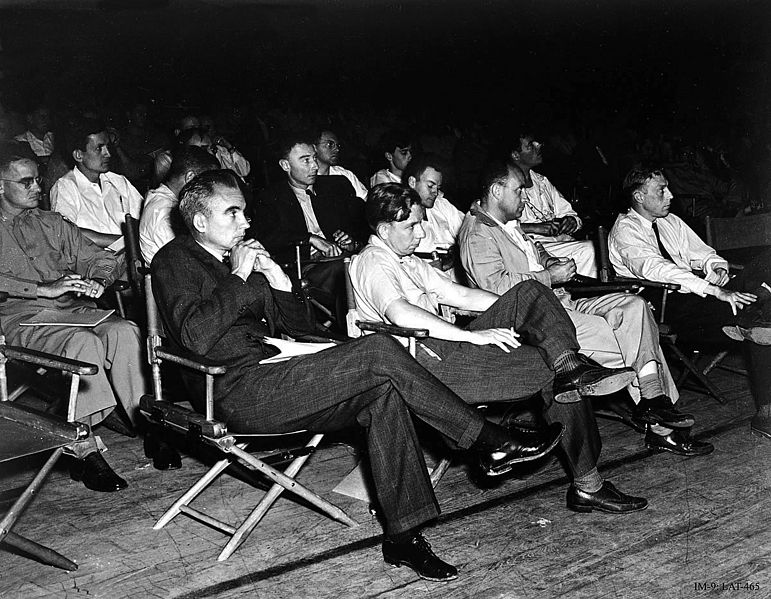

A

group of physicists at a 1946 Los Alamos colloquium. In

the front row are left to right: Norris Bradbury,

John Manley, Enrico Fermi and J.M.B. Kellogg (L-R). Behind

Manley is Oppenheimer (wearing jacket and tie),

and to his left is Richard Feynman. The army colonel on

the far left is Oliver Haywood.

In the third row between Haywood and Oppenheimer is Edward

Teller.

In

June 1942, the US Army established the Manhattan Engineer

District to handle its part in the atom bomb project,

beginning the process of transferring responsibility from

the Office of Scientific Research and Development to the

military. In September, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves,

Jr., was appointed director of what became known as the

Manhattan Project. Groves selected Oppenheimer to head

the project's secret weapons laboratory, a choice which

surprised many, as Oppenheimer was not known to be politically

aligned with the conservative military, nor to be an efficient

leader of large projects. The fact that he did not have

a Nobel Prize, and might not have the prestige to direct

fellow scientists, did concern Groves. However, he was

impressed by Oppenheimer's singular grasp of the practical

aspects of designing and constructing an atomic bomb,

and by the breadth of his knowledge. As a military engineer,

Groves knew that this would be vital in an interdisciplinary

project that would involve not just physics, but chemistry,

metallurgy, ordnance and engineering. Groves also detected

in Oppenheimer something that many others did not, an

"overweening ambition" that Groves reckoned

would supply the drive necessary to push the project to

a successful conclusion. Isidor Rabi considered the appointment

"a real stroke of genius on the part of General Groves,

who was not generally considered to be a genius".

Oppenheimer

and Groves decided that for security and cohesion they

needed a centralized, secret research laboratory in a

remote location. Scouting for a site in late 1942, Oppenheimer

was drawn to New Mexico, not far from his ranch. On November

16, 1942, Oppenheimer, Groves and others toured a prospective

site. Oppenheimer feared that the high cliffs surrounding

the site would make his people feel claustrophobic, while

the engineers were concerned with the possibility of flooding.

He then suggested and championed a site that he knew well:

a flat mesa near Santa Fe, New Mexico, which was the site

of a private boys' school called the Los Alamos Ranch

School. The engineers were concerned about the poor access

road and the water supply, but otherwise felt that it

was ideal. The Los Alamos Laboratory was built on the

site of the school, taking over some of its buildings,

while many others were erected in great haste. There,

Oppenheimer assembled a group of the top physicists of

the time, which he referred to as the "luminaries".

Initially,

Los Alamos was supposed to be a military laboratory, and

Oppenheimer and other researchers were to be commissioned

into the Army. He went so far as to order himself a lieutenant

colonel's uniform and take the Army physical test, which

he failed. Army doctors considered him underweight at

128 pounds (58 kg), diagnosed his chronic cough as tuberculosis

and were concerned about his chronic lumbosacral joint

pain. The plan to commission scientists fell through when

Robert Bacher and Isidor Rabi balked at the idea. Conant,

Groves, and Oppenheimer devised a compromise whereby the

laboratory was operated by the University of California

under contract to the War Department. It soon turned out

that Oppenheimer had hugely underestimated the magnitude

of the project; Los Alamos grew from a few hundred people

in 1943 to over 6,000 in 1945.

Oppenheimer,

at first, had difficulty with the organizational division

of large groups, but rapidly learned the art of large-scale

administration after he took up permanent residence on

the mesa. He was noted for his mastery of all scientific

aspects of the project and for his efforts to control

the inevitable cultural conflicts between scientists and

the military. He was an iconic figure to his fellow scientists,

as much a symbol of what they were working toward as a

scientific director. Victor Weisskopf put it thus:

Oppenheimer directed these studies, theoretical and experimental,

in the real sense of the words. Here, his uncanny speed

in grasping the main points of any subject was a decisive

factor; he could acquaint himself with the essential details

of every part of the work. He did not direct from the

head office. He was intellectually and even physically

present at each decisive step. He was present in the laboratory

or in the seminar rooms, when a new effect was measured,

when a new idea was conceived. It was not that he contributed

so many ideas or suggestions; he did so sometimes, but

his main influence came from something else. It was his

continuous and intense presence, which produced a sense

of direct participation in all of us; it created that

unique atmosphere of enthusiasm and challenge that pervaded

the place throughout its time.

In

1943, development efforts were directed to a plutonium

gun-type fission weapon called "Thin Man". Initial

research on the properties of plutonium was done using

cyclotron-generated plutonium-239, which was extremely

pure but could only be created in tiny amounts. When Los

Alamos received the first sample of plutonium from the

X-10 Graphite Reactor in April 1944, a problem was discovered:

reactor-bred plutonium had a higher concentration of plutonium-240,

making it unsuitable for use in a gun-type weapon. In

July 1944, Oppenheimer abandoned the gun design in favor

of an implosion-type weapon. Using chemical explosive

lenses, a sub-critical sphere of fissile material could

be squeezed into a smaller and denser form. The metal

needed to travel only very short distances, so the critical

mass would be assembled in much less time. In August 1944,

Oppenheimer implemented a sweeping reorganization of the

Los Alamos laboratory to focus on implosion. He concentrated

the development efforts on the gun-type device, a simpler

design that only had to work with uranium-235, in a single

group, and this device became Little Boy in February 1945.

After a mammoth research effort, the more complex design

of the implosion device, known as the "Christy gadget"

after Robert Christy, another student of Oppenheimer's,

was finalized in a meeting in Oppenheimer's office on

February 28, 1945.

Presentation

of the Army-Navy "E" Award at Los Alamos on

October 16, 1945.

Oppenheimer (left) gave his farewell speech as director

on this occasion. Robert Gordon

Sproul front, in suit, accepted the award on behalf of

the University of California.

In

May 1945, an Interim Committee was created to advise and

report on wartime and postwar policies regarding the use

of nuclear energy. The Interim Committee, in turn, established

a scientific panel consisting of Compton, Fermi, Lawrence

and Oppenheimer to advise it on scientific issues. In

its presentation to the Interim Committee, the scientific

panel offered its opinion not just on the likely physical

effects of an atomic bomb, but on its likely military

and political impact. This included opinions on such sensitive

issues as whether or not the Soviet Union should be advised

of the weapon in advance of its use against Japan.

Trinity

The

joint work of the scientists at Los Alamos resulted in

the first artificial nuclear explosion near Alamogordo

on July 16, 1945, on a site that Oppenheimer codenamed

"Trinity" in mid-1944. He later said this name

was from one of John Donne's Holy Sonnets. According to

the historian Gregg Herken, this naming could have been

an allusion to Jean Tatlock, who had committed suicide

a few months previously and had in the 1930s introduced

Oppenheimer to Donne's work. Oppenheimer later recalled

that, while witnessing the explosion, he thought of a

verse from the Hindu holy book, the Bhagavad Gita (XI,12):

If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at

once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of

the mighty one ...

Years

later, he would explain that another verse had also entered

his head at that time: namely, the famous verse: "ka-lo'smi

lokaks.ayakr.tpravr.ddho loka-nsama-hartumiha pravr.ttah."

(XI,32), which he translated as "I am become Death,

the destroyer of worlds."

In

1965, he was persuaded to quote again for a television

broadcast:

We knew the world would not be the same. A few people

laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent.

I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad

Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he

should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed

form and says, 'Now I am become Death, the destroyer of

worlds.' I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.

.jpg)

The

fireball at the Trinity nuclear test

According

to his brother, at the time Oppenheimer simply exclaimed,

"It worked." A contemporary account by Brigadier

General Thomas Farrell, who was present in the control

bunker at the site with Oppenheimer, summarized his reaction

as follows:

Dr. Oppenheimer, on whom had rested a very heavy burden,

grew tenser as the last seconds ticked off. He scarcely

breathed. He held on to a post to steady himself. For

the last few seconds, he stared directly ahead and then

when the announcer shouted "Now!" and there

came this tremendous burst of light followed shortly thereafter

by the deep growling roar of the explosion, his face relaxed

into an expression of tremendous relief.

Physicist

Isidor Rabi noticed Oppenheimer's disconcerting triumphalism:

"I'll never forget his walk; I'll never forget

the way he stepped out of the car ... his walk was like

High Noon ... this kind of strut. He had done it."

At an assembly at Los Alamos on August 6 (the evening

of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima), Oppenheimer took

to the stage and clasped his hands together "like

a prize-winning boxer" while the crowd cheered. He

noted his regret the weapon had not been available in

time to use against Nazi Germany. However, he and many

of the project staff were very upset about the bombing

of Nagasaki, as they did not feel the second bomb was

necessary from a military point of view. He traveled to

Washington on August 17 to hand-deliver a letter to Secretary

of War Henry L. Stimson expressing his revulsion and his

wish to see nuclear weapons banned.

For

his services as director of Los Alamos, Oppenheimer was

awarded the Medal for Merit from President Harry S. Truman

in 1946.

Postwar

activities

After

the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Manhattan

Project became public knowledge; and Oppenheimer became

a national spokesman for science, emblematic of a new

type of technocratic power. He became a household name

and his face appeared on the covers of Life and Time.

Nuclear physics became a powerful force as all governments

of the world began to realize the strategic and political

power that came with nuclear weapons. Like many scientists

of his generation, he felt that security from atomic bombs

would come only from a transnational organization such

as the newly formed United Nations, which could institute

a program to stifle a nuclear arms race.

Institute

for Advanced Study

In

November 1945, Oppenheimer left Los Alamos to return to

Caltech, but he soon found that his heart was no longer

in teaching. In 1947, he accepted an offer from Lewis

Strauss to take up the directorship of the Institute for

Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. This meant moving

back east and leaving Ruth Tolman, the wife of his friend

Richard Tolman, with whom he had begun an affair after

leaving Los Alamos. The job came with a salary of $20,000

per annum, plus rent-free accommodation in the director's

house, a 17th-century manor with a cook and groundskeeper,

surrounded by 265 acres (107 ha) of woodlands.

Institute

for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey

Oppenheimer

brought together intellectuals at the height of their

powers and from a variety of disciplines to solve the

most pertinent questions of the age. He directed and encouraged

the research of many well-known scientists, including

Freeman Dyson, and the duo of Chen Ning Yang and Tsung-Dao

Lee, who won a Nobel Prize for their discovery of parity

non-conservation. He also instituted temporary memberships

for scholars from the humanities, such as T. S. Eliot

and George F. Kennan. Some of these activities were resented

by a few members of the mathematics faculty, who wanted

the institute to stay a bastion of pure scientific research.

Abraham Pais said that Oppenheimer himself thought that

one of his failures at the institute was being unable

to bring together scholars from the natural sciences and

the humanities.

A

series of conferences in New York from 1947 through 1949

saw physicists switch back from war work to theoretical

issues. Under Oppenheimer's direction, physicists tackled

the greatest outstanding problem of the pre-war years:

infinite, divergent, and non-sensical expressions in the

quantum electrodynamics of elementary particles. Julian

Schwinger, Richard Feynman and Shin'ichiro Tomonaga tackled

the problem of regularization, and developed techniques

which became known as renormalization. Freeman Dyson was

able to prove that their procedures gave similar results.

The problem of meson absorption and Hideki Yukawa's theory

of mesons as the carrier particles of the strong nuclear

force were also tackled. Probing questions from Oppenheimer

prompted Robert Marshak's innovative two-meson hypothesis:

that there were actually two types of mesons, pions and

muons. This led to Cecil Frank Powell's breakthrough and

subsequent Nobel Prize for the discovery of the pion.

Atomic

Energy Commission

As

a member of the Board of Consultants to a committee appointed

by Truman, Oppenheimer strongly influenced the Acheson–Lilienthal

Report. In this report, the committee advocated creation

of an international Atomic Development Authority, which

would own all fissionable material and the means of its

production, such as mines and laboratories, and atomic

power plants where it could be used for peaceful energy

production. Bernard Baruch was appointed to translate

this report into a proposal to the United Nations, resulting

in the Baruch Plan of 1946. The Baruch Plan introduced

many additional provisions regarding enforcement, in particular

requiring inspection of the Soviet Union's uranium resources.

The Baruch Plan was seen as an attempt to maintain the

United States' nuclear monopoly and was rejected by the

Soviets. With this, it became clear to Oppenheimer that

an arms race was unavoidable, due to the mutual suspicion

of the United States and the Soviet Union, which even

Oppenheimer was starting to distrust.

Oppenheimer

in 1946

After

the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) came into being in

1947 as a civilian agency in control of nuclear research

and weapons issues, Oppenheimer was appointed as the Chairman

of its General Advisory Committee (GAC). From this position

he advised on a number of nuclear-related issues, including

project funding, laboratory construction and even international

policy — though the GAC's advice was not always heeded.

As Chairman of the GAC, Oppenheimer lobbied vigorously

for international arms control and funding for basic science,

and attempted to influence policy away from a heated arms

race. When the government questioned whether to pursue

a crash program to develop an atomic weapon based on nuclear

fusion — the hydrogen bomb — Oppenheimer initially

recommended against it, though he had been in favor of

developing such a weapon during the Manhattan Project.

He was motivated partly by ethical concerns, feeling that

such a weapon could only be used strategically against

civilian targets, resulting in millions of deaths. He

was also motivated by practical concerns, however, as

at the time there was no workable design for a hydrogen

bomb. Oppenheimer felt that resources would be better

spent creating a large force of fission weapons. He and

others were especially concerned about nuclear reactors

being diverted from plutonium to tritium production. They

were overridden by Truman, who announced a crash program

after the Soviet Union tested their first atomic bomb

in 1949. Oppenheimer and other GAC opponents of the project,

especially James Conant, felt personally shunned and considered

retiring from the committee. They stayed on, though their

views on the hydrogen bomb were well known.

In

1951, however, Edward Teller and mathematician Stanislaw

Ulam developed what became known as the Teller-Ulam design

for a hydrogen bomb. This new design seemed technically

feasible and Oppenheimer changed his opinion about developing

the weapon. As he later recalled:

The program we had in 1949 was a tortured thing that you

could well argue did not make a great deal of technical

sense. It was therefore possible to argue that you did

not want it even if you could have it. The program in

1951 was technically so sweet that you could not argue

about that. The issues became purely the military, the

political and the humane problems of what you were going

to do about it once you had it.

Security

hearing

The

FBI under J. Edgar Hoover had been following Oppenheimer

since before the war, when he showed Communist sympathies

as a professor at Berkeley and had been close to members

of the Communist Party, including his wife and brother.

He had been under close surveillance since the early 1940s,

his home and office bugged, his phone tapped and his mail

opened. The FBI furnished Oppenheimer's political enemies

with incriminating evidence about his Communist ties.

These enemies included Lewis Strauss, an AEC commissioner

who had long harbored resentment against Oppenheimer both

for his activity in opposing the hydrogen bomb and for

his humiliation of Strauss before Congress some years

earlier; regarding Strauss's opposition to the export

of radioactive isotopes to other nations, Oppenheimer

had memorably categorized these as "less important

than electronic devices but more important than, let us

say, vitamins."

President

Eisenhower (left) receives a report from Lewis L. Strauss

(right), Chairman of the Atomic

Energy Commission, on the Operation Castle hydrogen bomb

tests in the Pacific, March 30,

1954. Strauss pressed for Oppenheimer's security clearance

to be revoked.

On

June 7, 1949, Oppenheimer testified before the House Un-American

Activities Committee, where he admitted that he had associations

with the Communist Party in the 1930s. He testified that

some of his students, including David Bohm, Giovanni Rossi

Lomanitz, Philip Morrison, Bernard Peters and Joseph Weinberg,

had been Communists at the time they had worked with him

at Berkeley. Frank Oppenheimer and his wife Jackie testified

before the HUAC and admitted that they had been members

of the Communist Party. Frank was subsequently fired from

his University of Minnesota position. Unable to find work

in physics for many years, he became instead a cattle

rancher in Colorado. He later taught high school physics

and was the founder of the San Francisco Exploratorium.

Oppenheimer

had found himself in the middle of more than one controversy

and power struggle in the years from 1949 to 1953. Edward

Teller, who had been so uninterested in work on the atomic

bomb at Los Alamos during the war that Oppenheimer had

given him time instead to work on his own project of the

hydrogen bomb, had eventually left Los Alamos to help

found, in 1951, a second laboratory at what would become

the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. There, he

could be free of Los Alamos control to develop the hydrogen

bomb. Long-range thermonuclear "strategic" weapons

delivered by jet bombers would necessarily be under control

of the new United States Air Force (USAF). Oppenheimer

had, for some years, pushed for smaller "tactical"

nuclear weapons which would be more useful in a limited

theater against enemy troops and which would be under

control of the Army. The two services fought for control

of nuclear weapons, often allied with different political

parties. The USAF, with Teller pushing its program, gained

ascendance in the Republican-controlled administration

following the election of Dwight D. Eisenhower as president

in 1952.

Strauss

and Senator Brien McMahon, author of the 1946 McMahon

Act, pushed Eisenhower to revoke Oppenheimer's security

clearance. On December 21, 1953, Lewis Strauss told Oppenheimer

that his security clearance had been suspended, pending

resolution of a series of charges outlined in a letter,

and discussed his resigning. Oppenheimer chose not to

resign and requested a hearing instead. The charges were

outlined in a letter from Kenneth D. Nichols, General

Manager of the AEC. The hearing that followed in April–May

1954, which was initially confidential and not made public,

focused on Oppenheimer's past Communist ties and his association

during the Manhattan Project with suspected disloyal or

Communist scientists. One of the key elements in this

hearing was Oppenheimer's earliest testimony about George

Eltenton's approach to various Los Alamos scientists,

a story that Oppenheimer confessed he had fabricated to

protect his friend Haakon Chevalier. Unknown to Oppenheimer,

both versions were recorded during his interrogations

of a decade before. He was surprised on the witness stand

with transcripts of these, which he had not been given

a chance to review. In fact, Oppenheimer had never told

Chevalier that he had finally named him, and the testimony

had cost Chevalier his job. Both Chevalier and Eltenton

confirmed mentioning that they had a way to get information

to the Soviets, Eltenton admitting he said this to Chevalier

and Chevalier admitting he mentioned it to Oppenheimer,

but both put the matter in terms of gossip and denied

any thought or suggestion of treason or thoughts of espionage,

either in planning or in deed. Neither was ever convicted

of any crime.

.jpg)

Oppenheimer's

former colleague, physicist Edward Teller, testified on

behalf

of the government at Oppenheimer's security hearing in

1954.

Teller

testified that he considered Oppenheimer loyal, but that:

In a great number of cases, I have seen Dr. Oppenheimer

act — I understand that Dr. Oppenheimer acted —

in a way which was for me was exceedingly hard to understand.

I thoroughly disagreed with him in numerous issues and

his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated.

To this extent, I feel that I would like to see the vital

interests of this country in hands which I understand

better, and therefore trust more. In this very limited

sense I would like to express a feeling that I would feel

personally more secure if public matters would rest in

other hands.

This

led to outrage by the scientific community and Teller's

virtual expulsion from academic science. Groves, threatened

by the FBI as having been potentially part of a coverup

about the Chevalier contact in 1943, likewise testified

against Oppenheimer. Many top scientists, as well as government

and military figures, testified on Oppenheimer's behalf.

Inconsistencies in his testimony and his erratic behavior

on the stand, at one point saying he had given a "cock

and bull story" and that this was because he "was

an idiot", convinced some that he was unstable, unreliable

and a possible security risk. Oppenheimer's clearance

was revoked one day before it was due to lapse anyway.

Isidor Rabi's comment was that Oppenheimer was merely

a government consultant at the time anyway and that if

the government "didn't want to consult the guy, then

don't consult him."

During

his hearing, Oppenheimer testified willingly on the left-wing

behavior of many of his scientific colleagues. Had Oppenheimer's

clearance not been stripped then, he might have been remembered

as someone who had "named names" to save his

own reputation. As it happened, Oppenheimer was seen by

most of the scientific community as a martyr to McCarthyism,

an eclectic liberal who was unjustly attacked by warmongering

enemies, symbolic of the shift of scientific creativity

from academia into the military. Wernher von Braun summed

up his opinion about the matter with a quip to a Congressional

committee: "In England, Oppenheimer would have been

knighted."

In

a seminar at the Woodrow Wilson Institute on May 20, 2009,

based on an extensive analysis of the Vassiliev notebooks

taken from the KGB archives, John Earl Haynes, Harvey

Klehr and Alexander Vassiliev confirmed that Oppenheimer

never was involved in espionage for the Soviet Union.

The KGB tried repeatedly to recruit him, but was never

successful; Oppenheimer did not betray the United States.

In addition, he had several persons removed from the Manhattan

Project who had sympathies to the Soviet Union. According

to biographer Ray Monk: "He was, in a very practical

and real sense, a supporter of the Communist Party. Moreover,

in terms of the time, effort and money spent on Party

activities, he was a very committed supporter".

Final

years

Starting

in 1954, Oppenheimer spent several months of the year

living on the island of St. John in the Virgin Islands.

In 1957, he purchased a 2-acre (0.81 ha) tract of land

on Gibney Beach, where he built a spartan home on the

beach. He spent a considerable amount of time sailing

with his daughter Toni and wife Kitty.

Oppenheimer

Beach, in St John, US Virgin Islands

Increasingly

concerned about the potential danger to humanity arising

from scientific discoveries, Oppenheimer joined with Albert

Einstein, Bertrand Russell, Joseph Rotblat and other eminent

scientists and academics to establish what would eventually

become the World Academy of Art and Science in 1960. Significantly,

after his public humiliation, he did not sign the major

open protests against nuclear weapons of the 1950s, including

the Russell–Einstein Manifesto of 1955, nor, though

invited, did he attend the first Pugwash Conferences on

Science and World Affairs in 1957.

In

his speeches and public writings, Oppenheimer continually

stressed the difficulty of managing the power of knowledge

in a world in which the freedom of science to exchange

ideas was more and more hobbled by political concerns.

Oppenheimer delivered the Reith Lectures on the BBC in

1953, which were subsequently published as Science and

the Common Understanding. In 1955, Oppenheimer published

The Open Mind, a collection of eight lectures that he

had given since 1946 on the subject of nuclear weapons

and popular culture. Oppenheimer rejected the idea of

nuclear gunboat diplomacy. "The purposes of this

country in the field of foreign policy," he wrote,

"cannot in any real or enduring way be achieved by

coercion." In 1957, the philosophy and psychology

departments at Harvard invited Oppenheimer to deliver

the William James Lectures. An influential group of Harvard

alumni led by Edwin Ginn that included Archibald Roosevelt

protested against the decision. Some 1,200 people packed

into Sanders Theatre to hear Oppenheimer's six lectures,

entitled "The Hope of Order". Oppenheimer delivered

the Whidden Lectures at McMaster University in 1962, and

these were published in 1964 as The Flying Trapeze: Three

Crises for Physicists.

Deprived

of political power, Oppenheimer continued to lecture,

write and work on physics. He toured Europe and Japan,

giving talks about the history of science, the role of

science in society, and the nature of the universe. In

September 1957, France made him an Officer of the Legion

of Honor, and on May 3, 1962, he was elected a Foreign

Member of the Royal Society in Britain. At the urging

of many of Oppenheimer's political friends who had ascended

to power, President John F. Kennedy awarded Oppenheimer

the Enrico Fermi Award in 1963 as a gesture of political

rehabilitation. Edward Teller, the winner of the previous

year's award, had also recommended Oppenheimer receive

it, in the hope that it would heal the rift between them.

A little over a week after Kennedy's assassination, his

successor, President Lyndon Johnson, presented Oppenheimer

with the award, "for contributions to theoretical

physics as a teacher and originator of ideas, and for

leadership of the Los Alamos Laboratory and the atomic

energy program during critical years." Oppenheimer

told Johnson: "I think it is just possible, Mr.

President, that it has taken some charity and some courage

for you to make this award today." The rehabilitation

implied by the award was partly symbolic, as Oppenheimer

still lacked a security clearance and could have no effect

on official policy, but the award came with a $50,000

tax-free stipend, and its award outraged many prominent

Republicans in Congress. The late President Kennedy's

widow Jacqueline, still living in the White House, made

it a point to meet with Oppenheimer to tell him how much

her husband had wanted him to have the medal. While still

a senator in 1959, Kennedy had been instrumental in voting

to narrowly deny Oppenheimer's enemy Lewis Strauss a coveted

government position as Secretary of Commerce, effectively

ending Strauss' political career. This was partly due

to lobbying by the scientific community on behalf of Oppenheimer.

5

June 1947. Award of honorary degrees at Harvard to Oppenheimer

(left), George C.

Marshall (third from left) and Omar N. Bradley (fifth

from left). The President of

Harvard University, James B. Conant, sits between Marshall

and Bradley.

A

chain smoker since early adulthood, Oppenheimer was diagnosed

with throat cancer in late 1965 and, after inconclusive

surgery, underwent unsuccessful radiation treatment and

chemotherapy late in 1966. He fell into a coma on February

15, 1967, and died at his home in Princeton, New Jersey,

on February 18, aged 62. A memorial service was held at

Alexander Hall at Princeton University a week later, which

was attended by 600 of his scientific, political and military

associates, including Bethe, Groves, Kennan, Lilienthal,

Rabi, Smyth and Wigner. His brother Frank and the rest

of his family were there, as was the historian Arthur

Meier Schlesinger Jr., the novelist John O'Hara, and George

Balanchine, the director of the New York City Ballet.

Bethe, Kennan and Smyth gave brief eulogies. Oppenheimer

was cremated and his ashes were placed in an urn. Kitty

took his ashes to St. John and dropped the urn into the

sea off the coast, within sight of the beach house.

Upon

the death of Kitty Oppenheimer, who died of an intestinal

infection complicated by pulmonary embolism in October

1972, Oppenheimer's ranch in New Mexico was inherited

by their son Peter, and the beach property was inherited

by their daughter Katherine "Toni" Oppenheimer

Silber. Toni was refused security clearance for her chosen

vocation as a United Nations translator after the FBI

brought up the old charges against her father. In January

1977, three months after the end of her second marriage,

she committed suicide at age 32. She left the property

to "the people of St. John for a public park and

recreation area." The original house, built too close

to the coast, succumbed to a hurricane, but today, the

Virgin Islands Government maintains a Community Center

in the area.

Legacy

When

Oppenheimer was ejected from his position of political

influence in 1954, he symbolized for many the folly of

scientists thinking they could control how others would

use their research. He has also been seen as symbolizing

the dilemmas involving the moral responsibility of the

scientist in the nuclear world. The hearings were motivated

both by politics, as Oppenheimer was seen as a representative

of the previous administration, and by personal considerations

stemming from his enmity with Lewis Strauss. The ostensible

reason for the hearing and the issue that aligned Oppenheimer

with the liberal intellectuals, Oppenheimer's opposition

to hydrogen bomb development, was based as much on technical

grounds as on moral ones. Once the technical considerations

were resolved, he supported Teller's hydrogen bomb because

he believed that the Soviet Union would inevitably construct

one too. Rather than consistently oppose the "Red-baiting"

of the late 1940s and early 1950s, Oppenheimer testified

against some of his former colleagues and students, both

before and during his hearing. In one incident, his damning

testimony against former student Bernard Peters was selectively

leaked to the press. Historians have interpreted this

as an attempt by Oppenheimer to please his colleagues

in the government and perhaps to divert attention from

his own previous left-wing ties and those of his brother.

In the end, it became a liability when it became clear

that if Oppenheimer had really doubted Peters' loyalty,

his recommending him for the Manhattan Project was reckless,

or at least contradictory.

Oppenheimer

(left) and Groves (right) at the remains of the Trinity

test in September 1945.

The white canvas overshoes prevent fallout from sticking

to the soles of their shoes.

Popular

depictions of Oppenheimer view his security struggles

as a confrontation between right-wing militarists (symbolized

by Teller) and left-wing intellectuals (symbolized by

Oppenheimer) over the moral question of weapons of mass

destruction. The question of the scientists' responsibility

toward humanity inspired Bertolt Brecht's drama Galileo

(1955), left its imprint on Friedrich Dürrenmatt's

Die Physiker, and is the basis of the opera Doctor Atomic

by John Adams (2005), which was commissioned to portray

Oppenheimer as a modern-day Faust. Heinar Kipphardt's

play In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, after appearing

on West German television, had its theatrical release

in Berlin and Munich in October 1964. Oppenheimer's objections

resulted in an exchange of correspondence with Kipphardt,

in which the playwright offered to make corrections but

defended the play. It premiered in New York in June 1968,

with Joseph Wiseman in the Oppenheimer role. New York

Times theater critic Clive Barnes called it an "angry

play and a partisan play" that sided with Oppenheimer

but portrayed the scientist as a "tragic fool and

genius". Oppenheimer had difficulty with this portrayal.

After reading a transcript of Kipphardt's play soon after

it began to be performed, Oppenheimer threatened to sue

the playwright, decrying "improvisations which were

contrary to history and to the nature of the people involved."

Later, Oppenheimer told an interviewer:

The whole damn thing [his security hearing] was a farce,

and these people are trying to make a tragedy out of it.

... I had never said that I had regretted participating

in a responsible way in the making of the bomb. I said

that perhaps he [Kipphardt] had forgotten Guernica, Coventry,

Hamburg, Dresden, Dachau, Warsaw, and Tokyo; but I had

not, and that if he found it so difficult to understand,

he should write a play about something else.

The

1980 BBC TV serial Oppenheimer, starring Sam Waterston,

won three BAFTA Television Awards. The Day After Trinity,

a 1980 documentary about J. Robert Oppenheimer and the

building of the atomic bomb, was nominated for an Academy

Award and received a Peabody Award. In addition to his

use by authors of fiction, Oppenheimer's life has been

explored in numerous biographies, including American Prometheus:

The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2005)

by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin which won the Pulitzer

Prize for Biography or Autobiography for 2006. A centennial

conference and exhibit were held in 2004 at Berkeley,

with the proceedings of the conference published in 2005

as Reappraising Oppenheimer: Centennial Studies and Reflections.

His papers are in the Library of Congress.

As

a scientist, Oppenheimer is remembered by his students

and colleagues as being a brilliant researcher and engaging

teacher, the founder of modern theoretical physics in

the United States. Because his scientific attentions often

changed rapidly, he never worked long enough on any one

topic and carried it to fruition to merit the Nobel Prize,

although his investigations contributing to the theory

of black holes may have warranted the prize had he lived

long enough to see them brought into fruition by later

astrophysicists. An asteroid, 67085 Oppenheimer, was named

in his honor, as was the lunar crater Oppenheimer.

As

a military and public policy advisor, Oppenheimer was

a technocratic leader in a shift in the interactions between

science and the military and the emergence of "Big

Science". During World War II, scientists became

involved in military research to an unprecedented degree.

Because of the threat fascism posed to Western civilization,

they volunteered in great numbers both for technological

and organizational assistance to the Allied effort, resulting

in such powerful tools as radar, the proximity fuse and

operations research. As a cultured, intellectual, theoretical

physicist who became a disciplined military organizer,

Oppenheimer represented the shift away from the idea that

scientists had their "head in the clouds" and

that knowledge on such previously esoteric subjects as

the composition of the atomic nucleus had no "real-world"

applications.

Two

days before the Trinity test, Oppenheimer expressed his

hopes and fears in a quotation from the Bhagavad Gita:

In battle, in the forest, at the precipice in the mountains,

On the dark great sea, in the midst of javelins and arrows,

In sleep, in confusion, in the depths of shame,

The good deeds a man has done before defend him.

Robert

Oppenheimer and Fying Saucers

In

June of 1947 Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer

together wrote a TOP SECRET six-page document entitled

"Relationships with Inhabitants of Celestial Bodies".

It

says the presence of unidentified spacecraft is accepted

as de facto by the military.

It

also deals with the subjects that you would expect competent

scientists to deal with - i.e., where do they come from,

what does the law say about it, what should we do in the

event of colonization and/or integration of peoples, and

why are they here?

Finally,

the document addresses the presence of celestial astroplanes

in our atmosphere as a result of actions of military experiments

with fission and fusion devices of warfare.

Einstein

and Oppenheimer encourage consideration of our potential

future situation and safety due to our present and past

actions in space. How can we avoid a perilous fate?

Extract

majestic document:

Relationships

with extraterrestrial men presents no basically new problem

from the standpoint of international law; but the possibility

of confronting intelligent beings that do not belong to

the human race would bring up problems whose solution

it is difficult to conceive.

In

principle, there is no difficulty in accepting the possibility

of coming to an understanding with them, and of establishing

all kinds of relationships.

If

these intelligent beings were in possession of a more

or less culture, and a more or less perfect political

organization, they would have an absolute right to be

recognized as independent and sovereign peoples.

Another

possibility may exist, that a species of homo sapiens

might have established themselves as an independent nation

on another celestial body in our solar system and evolved

culturely independently from ours.

Living

conditions on these bodies lets say the moon,-or the planet

Mars, would have to be such as to permit a stable, and

to a certain extent, independent life, from an economic

standpoint.

Much

has been speculated about the possibilities for life existing

outside of our atmosphere and beyond, always hypothetically.

Lets assume that magnesium silicates on the moon may exist

and contain up to 13 per cent water. Using energy and

machines brought to the moon, perhaps from a space station,

the rooks could be broken up, pulverized, and then backed

to drive off the water of crystallization. This could

be collected and then decomposed into hydrogen and oxygen,

using an electric. current or the short wave radiation

of the sun. The oxygen could be used for breathing purposes;

the hydrogen night be used as a fuel.

Now

we come to the problem of determining what to do if the

inhabitants of celestial bodies, or extraterrestrial biological

entitles (EBE) desire to settle here.

1.

If they are politically organised and possess a certain

culture similar to our own, they may be recognized as

a independent people.

2. If they consider our culture to be devoid of political

unity, they would have the right to colonize. Of course,

this colonization cannot be conducted on classic linos.

A superior form of colonizing will have to be conceived,

that could be a kind of tutelage, possibly through the

tacit approval of the United Nations. But would the United

Nations legally have the right of allowing such tutelage

over us in such a fashion?

We

cannot exclude the possibility that a race of extraterrestrial

people more advanced technologically and economically

may take upon itself the right to occupy another celestial

body.

The

division of a celestial body into zones and the distribution

of them among other celestial states.

A

moral entity? The most feasible solution it seem would

be this one, submit an agreement providing far the peaceful

absorbtion of a celestial race(s) in such a manner that

our culture would remain intact with guarantees that their

presence not be revealed.

It

would merely be a matter of internationalizing celestial

peoples, and creating an international treaty instrument.

The

presence of celestial astroplanes in our atmosphere is

a direct result of our testing atomic weapons?

The

presence of unidentified space craft flying in our atmosphere

(and possibly maintaining orbits about our planet) is

now, however, accepted by our military.

Military

strategists foresee the use of space craft with nuclear

warheads as the ultimate weapon of war. Attack no longer

comes from an exclusive direction, nor from a determined

country, but from the sky, with the practical impossibility

of determining who the aggressor is.

When

artificial satellites and missiles find their place in

space, we must consider the potential threat that unidentified

space craft pose. One must consider the fact that mis-identification

of these space craft for a intercontinental missile in

a re-entry phase of flight could lead to accidental nuclear

war.

This

document was written in 1947!!