Curtis

Emerson LeMay (November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990)

was a general in the United States Air Force and the vice

presidential running mate of American Independent Party

presidential candidate George Wallace in 1968.

He

is credited with designing and implementing an effective,

but also controversial, systematic strategic bombing campaign

in the Pacific theater of World War II. During the war,

he was known for planning and executing a massive bombing

campaign against cities in Japan and a crippling minelaying

campaign of Japan's internal waterways. After the war,

he headed the Berlin airlift, then reorganized the Strategic

Air Command (SAC) into an effective instrument of nuclear

war.

Early

life and career

Curtis

Emerson LeMay was born in Columbus, Ohio, on November

15, 1906. His father, Erving LeMay, was at times an ironworker

and general handyman, but he never held a job longer than

a few months. His mother, Arizona Dove (Carpenter) LeMay,

did her best to hold her family together. With very limited

income, his family moved around the country as his father

looked for work, going as far as Montana and California.

Eventually, they returned to his native city of Columbus.

LeMay attended Columbus public schools, graduating from

Columbus South High School, and studied civil engineering

at Ohio State University. Working his way through college,

he graduated with a bachelor's degree in civil engineering.

While at Ohio State he was a member of the National Society

of Pershing Rifles and the Professional Engineering Fraternity

Theta Tau. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in

the Air Corps Reserve in October 1929. He received a regular

commission in the United States Army Air Corps in January

1930. While finishing at Ohio State, he took flight training

at Norton Field in Columbus, in 1931–32. On June

9, 1934, he married Helen E. Maitland (died 1992), with

whom he had one child, Patricia Jane LeMay Lodge, known

as Janie.

LeMay

became a pursuit pilot and, while stationed in Hawaii,

became one of the first members of the Air Corps to receive

specialized training in aerial navigation. In August 1937,

as navigator under pilot and commander Caleb V. Haynes

on a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, he helped locate the

battleship Utah despite being given the wrong coordinates

by Navy personnel, in exercises held in misty conditions

off California, after which the group of B-17s bombed

it with water bombs. For Haynes again, in May 1938, he

navigated three B-17s over 610 miles (980 km) of the Atlantic

Ocean to intercept the Italian liner Rex to illustrate

the ability of land-based airpower to defend the American

coasts. In 1940, he was navigator for Haynes on the prototype

Boeing XB-15 heavy bomber, flying a survey from Panama

over the Galapagos islands. War brought rapid promotion

and increased responsibility.

When

his crews were not flying missions, they were being subjected

to his relentless training, as he believed that training

was the key to saving their lives. LeMay was widely and

fondly known among his troops as "Old Iron Pants"

throughout his career, also the "Big Cigar".

World

War II

When

the U.S. entered World War II in December 1941, LeMay

was a major in the United States Army Air Forces (he had

been a 1st lieutenant as recently as 1940), and the commander

of a newly created B-17 Flying Fortress unit, the 305th

Bomb Group. He took this unit to England in October 1942

as part of the Eighth Air Force, and led it in combat

until May 1943, notably helping to develop the combat

box formation. In September 1943 he became the first commander

of the newly-formed 3d Air Division. He personally led

several dangerous missions, including the Regensburg section

of the Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission of August 17, 1943.

In that mission he led 146 B-17s to Regensburg, Germany,

beyond the range of escorting fighters, and, after bombing,

continued on to bases in North Africa, losing 24 bombers

in the process. The heavy losses in veteran crews on this

and subsequent deep penetration missions in the autumn

of 1943 led the Eighth Air Force to limit missions to

targets within escort range. Finally, with the deployment

in the European theater of the North American P-51 Mustang

in January 1944, the Eighth Air Force gained an escort

fighter with range to match the bombers.

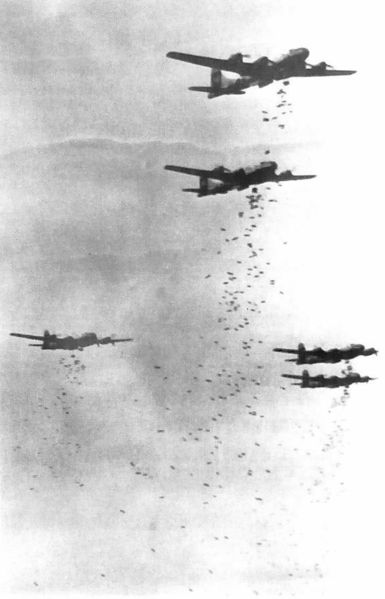

LeMay

became known for his massive incendiary attacks against

Japanese

cities during the war using hundreds of planes flying

at low altitudes.

Robert

McNamara described LeMay's character, in a discussion

of a report into high abort rates in bomber missions during

World War II:

"One of the commanders was Curtis LeMay—Colonel

in command of a B-24 [sic] group. He was the finest combat

commander of any service I came across in war. But he

was extraordinarily belligerent, many thought brutal.

He got the report. He issued an order. He said, 'I will

be in the lead plane on every mission. Any plane that

takes off will go over the target, or the crew will be

court-martialed.' The abort rate dropped overnight. Now

that's the kind of commander he was."

In

August 1944, LeMay transferred to the China-Burma-India

theater and directed first the XX Bomber Command in China

and then the XXI Bomber Command in the Pacific. LeMay

was later placed in charge of all strategic air operations

against the Japanese home islands.

LeMay

soon concluded that the techniques and tactics developed

for use in Europe against the Luftwaffe were unsuitable

against Japan. His Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers flying

from China were dropping their bombs near their targets

only 5% of the time. Operational losses of aircraft and

crews were unacceptably high owing to Japanese daylight

air defenses and continuing mechanical problems with the

B-29. In January 1945, LeMay was transferred from China

to relieve Brig. Gen. Haywood S. Hansell as commander

of the XXI Bomber Command in the Marianas.

He

became convinced that high-altitude precision bombing

would be ineffective, given the usually cloudy weather

over Japan. Furthermore, bombs dropped from the B-29s

at high altitude (20,000+ feet) were often blown off of

their trajectories by a consistently powerful jet stream

over the Japanese home islands, which dramatically reduced

the effectiveness of the high-altitude raids. Because

Japanese air defenses made daytime bombing below jet stream-affected

altitudes too perilous, LeMay finally switched to low-altitude

nighttime incendiary attacks on Japanese targets, a tactic

senior commanders had been advocating for some time. Japanese

cities were largely constructed of combustible materials

such as wood and paper. Precision high-altitude daylight

bombing was ordered to proceed only when weather permitted

or when specific critical targets were not vulnerable

to area bombing. General LeMay was informed by a senior

staff member, Colonel William P. Fisher, that bomber pilots

were turning back from these low altitude bombing runs

due to heavy anti-aircraft fire from Japanese defense

forces. Fisher suggested to Lemay that crews who achieved

successful strike rates should be rewarded by being released

from their deployment. LeMay implemented this unorthodox

plan and the strike rate went up to eighty percent.

LeMay

commanded subsequent B-29 Superfortress combat operations

against Japan, including massive incendiary attacks on

67 Japanese cities. This included the firebombing of Tokyo

on the night of March 9–10, 1945, the most destructive

bombing raid of the war. For this first attack, LeMay

ordered the defensive guns removed from 325 B-29s, loaded

each plane with Model M-47 incendiary clusters, magnesium

bombs, white phosphorus bombs, and napalm, and ordered

the bombers to fly in streams at 5,000 to 9,000 feet over

Tokyo.

The

first pathfinder airplanes arrived over Tokyo just after

midnight on March 10. Following British bombing practice,

they marked the target area with a flaming "X."

In a three-hour period, the main bombing force dropped

1,665 tons of incendiary bombs, killing 100,000 civilians,

destroying 250,000 buildings, and incinerating 16 square

miles (41 km2) of the city. Aircrews at the tail end of

the bomber stream reported that the stench of burned human

flesh permeated the aircraft over the target.

Precise

figures are not available, but the firebombing campaign

against Japan, directed by LeMay between March 1945 and

the Japanese surrender in August 1945, may have killed

more than 500,000 Japanese civilians and left five million

homeless. Official estimates from the United States Strategic

Bombing Survey put the figures at 220,000 people killed.

Some 40% of the built-up areas of 66 cities were destroyed,

including much of Japan's war industry.

The

remaining Allied prisoners of war in Japan who had survived

imprisonment to that time were frequently subjected to

additional reprisals and torture after an air raid. The

massive bombing also hit a number of prisons and directly

killed a number of Allied war prisoners.

LeMay

was aware of the implication of his orders. The New York

Times reported at the time, "Maj. Gen. Curtis

E. LeMay, commander of the B-29s of the entire Marianas

area, declared that if the war is shortened by a single

day, the attack will have served its purpose."

The argument was that it was his duty to carry out the

attacks in order to end the war as quickly as possible,

sparing further loss of life. He also remarked that had

the U.S. lost the war, he fully expected to be tried for

war crimes.

Presidents

Roosevelt and Truman justified these tactics by referring

to an estimate of one million Allied casualties if Japan

had to be invaded. Japan had intentionally decentralized

90 percent of its war-related production into small subcontractor

workshops in civilian districts, making remaining Japanese

war industry largely immune to conventional precision

bombing with high explosives.

As

the firebombing campaign took effect, Japanese war planners

were forced to expend significant resources to relocate

vital war industries to remote caves and mountain bunkers,

reducing production of war material. As a Lieutenant Colonel

who served under LeMay, Robert McNamara was in charge

of evaluating the effectiveness of American bombing missions.

Later, McNamara, as Secretary of Defense under Kennedy

and Johnson, would often clash with LeMay.

LeMay

also oversaw Operation Starvation, an aerial mining operation

against Japanese waterways and ports that disrupted Japanese

shipping and food distribution. Although his superiors

were unsupportive of this naval objective, LeMay gave

it a high priority by assigning the entire 313th Bombardment

Wing (four groups, about 160 airplanes) to the task. Aerial

mining supplemented a tight Allied submarine blockade

of the home islands, drastically reducing Japan's ability

to supply its overseas forces to the point that postwar

analysis concluded that it could have defeated Japan on

its own had it begun earlier.

Japan–Washington

flight

LeMay

piloted one of three specially modified B-29s flying from

Japan to the U.S. in September 1945, in the process breaking

several aviation records at that date, including the greatest

USAAF takeoff weight, the longest USAAF non-stop flight,

and the first ever non-stop Japan–Chicago flight.

One of the pilots was of higher rank: Lieutenant General

Barney Giles. The other two aircraft used up more fuel

than LeMay's in fighting headwinds, and they could not

fly to Washington, DC, the original goal. Their pilots

decided to land in Chicago to refuel. LeMay's aircraft

had sufficient fuel to reach Washington, but he was directed

by the War Department to join the others by refueling

at Chicago. The order was ostensibly given because of

borderline weather conditions in Washington, but according

to First Lieutenant Ivan J. Potts who was on board, the

order came because LeMay had one fewer general's stars

and should not be seen to outperform his superior.

Cold

War

Berlin

Airlift

After

World War II, LeMay was briefly transferred to The Pentagon

as deputy chief of Air Staff for Research & Development.

In 1947, he returned to Europe as commander of USAF Europe,

heading operations for the Berlin Airlift in 1948 in the

face of a blockade by the Soviet Union and its satellite

states that threatened to starve the civilian population

of the Western occupation zones of Berlin. Under LeMay's

direction, Douglas C-54 Skymasters that could each carry

10 tons of cargo began supplying the city on July 1. By

the fall, the airlift was bringing in an average of 5,000

tons of supplies a day. The airlift continued for 11 months—213,000

flights—that brought in 1.7 million tons of food

and fuel to Berlin. Faced with the failure of its blockade,

the Soviet Union relented and reopened land corridors

to the West. Though LeMay is sometimes publicly credited

with the success of the Berlin Airlift, it was, in fact,

instigated by General Lucius D. Clay when General Clay

called LeMay about the problem. LeMay initially started

flying supplies into Berlin, but then decided that it

was a job for a logistics expert and he found that person

in Lt. General William H. Tunner, who took over the operational

end of the Berlin Airlift.

General Curtis E. LeMay

Strategic

Air Command

In

1948, he returned to the US to head the Strategic Air

Command (SAC) at Offutt Air Force Base, replacing Gen

George Kenney. When LeMay took over command of SAC, it

consisted of little more than a few understaffed B-29

bombardment groups left over from World War II. Less than

half of the available aircraft were operational, and the

crews were undertrained. Base and aircraft security standards

were minimal. Upon inspecting a SAC hangar full of US

nuclear strategic bombers, LeMay found a single Air Force

sentry on duty, armed only with a ham sandwich. After

ordering a mock bombing exercise on Dayton, Ohio, LeMay

was shocked to learn that most of the strategic bombers

assigned to the mission missed their targets by one mile

or more. "We didn't have one crew, not one crew,

in the entire command who could do a professional job"

noted LeMay.

In

1949, LeMay was first to propose that a nuclear war be

conducted by delivering the nuclear arsenal in a single

overwhelming blow, going as far as "killing a nation".

Upon

receiving his fourth star in 1951 at age 44, LeMay became

the youngest four-star general in American history since

Ulysses S. Grant and was the youngest four-star general

in modern history as well as the longest serving in that

rank. In 1956 and 1957 LeMay implemented tests of 24-hour

bomber and tanker alerts, keeping some bomber forces ready

at all times. LeMay headed SAC until 1957, overseeing

its transformation into a modern, efficient, all-jet force.

LeMay's tenure was the longest over an American military

command in close to 100 years.

Despite

popular claims that LeMay advanced the notion of preventive

nuclear war, the historical record indicates LeMay actually

advocated justified preemptive nuclear war. Several documents

show LeMay advocating preemptive attack of the Soviet

Union, had it become clear the Soviets were preparing

to attack SAC or the US. In these documents, which were

often the transcripts of speeches before groups such as

the National War College or events such as the 1955 Joint

Secretaries Conference at the Quantico Marine Corps Base,

LeMay clearly advocated using SAC as a preemptive weapon,

if and when such was necessary.

The

"Airpower Battle"

General

LeMay was instrumental in SAC's acquisition of a large

fleet of new strategic bombers, establishment of a vast

aerial refueling system, the formation of many new units

and bases, development of a strategic ballistic missile

force, and establishment of a strict command and control

system with an unprecedented readiness capability. All

of this was protected by a greatly enhanced and modernized

security force, the Strategic Air Command Elite Guard.

LeMay insisted on rigorous training and very high standards

of performance for all SAC personnel, be they officers,

enlisted men, aircrews, mechanics, or administrative staff,

and reportedly commented, "I have neither the time

nor the inclination to differentiate between the incompetent

and the merely unfortunate."

A

famous legend often used by SAC flight crews to illustrate

LeMay's command style concerned his famous ever-present

cigar. In the first known published account of the story,

Life Magazine reporter Ernest Havemann related that LeMay

once took the co-pilot's seat of a SAC bomber to observe

the mission, complete with lit cigar. When asked by the

pilot to put the cigar out, LeMay demanded to know why.

When the pilot explained that fumes inside the fuselage

could ignite the airplane, LeMay reportedly growled, "It

wouldn't dare." The incident in the article was later

used as the basis for a fictional scene in the 1955 film

Strategic Air Command. In his highly controversial and

factually disputed memoir War's End, Major General Charles

Sweeney related an alleged 1944 incident that may have

been the basis for the "It wouldn't dare" comment.

Despite

his uncompromising attitude regarding performance of duty,

LeMay was also known for his concern for the physical

well-being and comfort of his men. LeMay found ways to

encourage morale, individual performance, and the reenlistment

rate through a number of means: encouraging off-duty group

recreational activities, instituting spot promotions based

on performance, and authorizing special uniforms, training,

equipment, and allowances for ground personnel as well

as flight crews.

On

LeMay's departure, SAC was composed of 224,000 airmen,

close to 2,000 heavy bombers, and nearly 800 tanker aircraft.

LeMay

was an active amateur radio operator and held a succession

of call signs; K0GRL, K4FRA, and W6EZV. He held these

calls respectively while stationed at Offutt AFB, Washington,

D.C. and when he retired in California. K0GRL is still

the call sign of the Strategic Air Command Memorial Amateur

Radio Club. He was famous for being on the air on amateur

bands while flying on board SAC bombers. LeMay became

aware that the new single sideband (SSB) technology offered

a big advantage over amplitude modulation (AM) for SAC

aircraft operating long distances from their bases. In

conjunction with Art Collins (W0CXX) of Collins Radio,

he established SSB as the radio standard for SAC bombers

in 1957.

LeMay

was appointed Vice Chief of Staff of the United States

Air Force in July 1957, serving until 1961, when he was

made the fifth Chief of Staff of the United States Air

Force on the retirement of Gen Thomas White. His belief

in the efficacy of strategic air campaigns over tactical

strikes and ground support operations became Air Force

policy during his tenure as chief of staff.

As

chief of staff, LeMay clashed repeatedly with Secretary

of Defense Robert McNamara, Air Force Secretary Eugene

Zuckert, and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff,

Army General Maxwell Taylor. At the time, budget constraints

and successive nuclear war fighting strategies had left

the armed forces in a state of flux. Each of the armed

forces had gradually jettisoned realistic appraisals of

future conflicts in favor of developing its own separate

nuclear and nonnuclear capabilities. At the height of

this struggle, the U.S. Army had even reorganized its

combat divisions to fight land wars on irradiated nuclear

battlefields, developing short-range atomic cannon and

mortars in order to win appropriations. The United States

Navy in turn proposed delivering strategic nuclear weapons

from supercarriers intended to sail into range of the

Soviet air defense forces. Of all these various schemes,

only LeMay's command structure of SAC survived complete

reorganization in the changing reality of Cold War-era

conflicts.

Though

LeMay lost significant appropriation battles for the Skybolt

ALBM and the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress replacement, the

North American XB-70 Valkyrie, he was largely successful

at expanding Air Force budgets. He advocated the introduction

of satellite technology and pushed for the development

of the latest electronic warfare techniques. By contrast,

the U.S. Army and Navy frequently suffered budgetary cutbacks

and program cancellations by Congress and Secretary McNamara.

During

the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, LeMay clashed again

with U.S. President John F. Kennedy and Defense Secretary

McNamara, arguing that he should be allowed to bomb nuclear

missile sites in Cuba. He opposed the naval blockade and,

after the end of the crisis, suggested that Cuba be invaded

anyway, even after the Russians agreed to withdraw. LeMay

called the peaceful resolution of the crisis "the

greatest defeat in our history". Unknown to the US,

the Soviet field commanders in Cuba had been given authority

to launch—the only time such authority was delegated

by higher command. They had twenty nuclear warheads for

medium-range R-12 Dvina (NATO Code SS-4 Sandal) ballistic

missiles capable of reaching US cities (including Washington)

and nine tactical nuclear missiles. If Soviet officers

had launched them, many millions of US citizens could

have been killed. The ensuing SAC retaliatory thermonuclear

strike would have killed roughly one hundred million Soviet

citizens. Kennedy refused LeMay's requests, however, and

the naval blockade was successful.

The

memorandum from LeMay, Chief of Staff, USAF, to the Joint

Chiefs of Staff, January 4, 1964, illustrates LeMay's

reasons for keeping bomber forces alongside ballistic

missiles: "It is important to recognize, however,

that ballistic missile forces represent both the U.S.

and Soviet potential for strategic nuclear warfare at

the highest, most indiscriminate level, and at a level

least susceptible to control. The employment of these

weapons in lower level conflict would be likely to escalate

the situation, uncontrollably, to an intensity which could

be vastly disproportionate to the original aggravation.

The use of ICBMs and SLBMs is not, therefore, a rational

or credible response to provocations which, although serious,

are still less than an immediate threat to national survival.

For this reason, among others, I consider that the national

security will continue to require the flexibility, responsiveness,

and discrimination of manned strategic weapon systems

throughout the range of cold, limited, and general war."

LeMay's

dislike for tactical aircraft and training backfired in

the low-intensity conflict of Vietnam, where existing

Air Force fighter aircraft and standard attack profiles

proved incapable of carrying out sustained tactical bombing

campaigns in the face of hostile North Vietnamese antiaircraft

defenses. LeMay said, "Flying fighters is fun.

Flying bombers is important." Aircraft losses

on tactical attack missions soared, and Air Force commanders

soon realized that their large, missile-armed jet fighters

were exceedingly vulnerable not only to antiaircraft shells

and missiles but also to cannon-armed, maneuverable Soviet

fighters.

LeMay

advocated a sustained strategic bombing campaign against

North Vietnamese cities, harbors, ports, shipping, and

other strategic targets. His advice was ignored. Instead,

an incremental policy was implemented that focused on

limited interdiction bombing of fluid enemy supply corridors

in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. This limited campaign

failed to destroy significant quantities of enemy war

supplies or diminish enemy ambitions. Bombing limitations

were imposed by President Lyndon Johnson for geopolitical

reasons, as he surmised that bombing Soviet and Chinese

ships in port and killing Soviet advisers would bring

the Soviets and Chinese more directly into the war.

Evidence

of LeMay's thinking is that, in his 1965 autobiography

(co-written with MacKinlay Kantor) LeMay is quoted as

saying his response to North Vietnam would be to demand

that "they’ve got to draw in their horns and

stop their aggression, or we’re going to bomb them

back into the Stone Age. And we would shove them back

into the Stone Age with Air power or Naval power—not

with ground forces."

Some

military historians have argued that LeMay's theories

were eventually proven correct. Near the war's end in

December 1972, President Richard Nixon ordered Operation

Linebacker II, a high-intensity Air Force, Navy, and Marine

Corps aerial bombing campaign, which included hundreds

of B-52 bombers that struck previously untouched North

Vietnamese strategic targets, including heavy populated

areas in Hanoi and Haiphong. Linebacker II was followed

by renewed negotiations that led to the Paris Peace Agreement,

appearing to support the claim. However, consideration

must be given to significant differences in terms of both

military obejctives and geopolitical realities between

1968 and 1972, including the impact of Nixon's recognition

and exploitation of the Sino-Soviet split to gain a "free

hand" in Vietnam and the shift of Communist opposition

from a organic insurgency (the Viet Cong) to a conventional

mechanized offensive that was by its nature more reliant

on industrial output and traditional logistics. In effect,

Johnson and Nixon were waging two different wars.

Post-military

career

Owing

to his unrelenting opposition to the Johnson administration's

Vietnam policy and what was widely perceived as his hostility

to Secretary McNamara, LeMay was essentially forced into

retirement in February 1965 and seemed headed for a political

career.[citation needed] Moving to California, he was

approached by conservatives to challenge moderate Republican

Thomas Kuchel for his seat in the United States Senate

in 1968, but he declined. For the presidential race that

year, LeMay originally supported Richard Nixon; he turned

down two requests by George Wallace to join his American

Independent Party that year on the grounds that a third-party

candidacy might hurt Nixon's chances at the polls (by

coincidence, Wallace had served as a sergeant in a unit

commanded by LeMay during World War II). LeMay gradually

became convinced that Nixon planned to pursue a conciliatory

policy with the Soviets and accept nuclear parity rather

than retain America's first-strike supremacy. LeMay felt

that Lyndon Johnson had lied to him on several occasions

and that Hubert Humphrey, if elected, would do the same.[citation

needed] Consequently LeMay, while being fully aware of

Wallace's segregationist platform, decided to throw his

support to Wallace and eventually became Wallace's running

mate. The general was dismayed to find himself attacked

in the press as a racial segregationist because he was

running with Wallace; he had never considered himself

a bigot. When Wallace announced his selection in October

1968, LeMay opined that he, unlike many Americans, clearly

did not fear using nuclear weapons. His saber rattling

did not help the Wallace campaign.

During

the 1968 campaign, LeMay became widely associated with

the "Stone Age" comment, especially because

he had suggested use of nuclear weapons as a strategy

to quickly resolve a deeply protracted conventional war

which eventually claimed over 50,000 American lives. This

reputation did nothing to diminish perceptions of extremism

in the Wallace-LeMay ticket. General LeMay disclaimed

the comment, saying in a later interview: "I never

said we should bomb them back to the Stone Age. I said

we had the capability to do it."

The

Wallace-LeMay AIP ticket received 13.5 percent of the

popular vote, higher than most third-party candidacies

in the US, and carried five states for a total of 46 electoral

votes.

He

was honored by several countries, receiving the Air Medal

with three oak leaf clusters, the Distinguished Flying

Cross with two oak leaf clusters, the Distinguished Service

Cross, Distinguished Service Medal with two oak leaf clusters,

the French Légion d'honneur and the Silver Star.

On December 7, 1964 the Japanese government conferred

on him the First Order of Merit with the Grand Cordon

of the Order of the Rising Sun. He was elected to the

Alfalfa Club in 1957 and served as a general officer for

21 years.

According

to historian Warren Kozak, Wallace's defeat left LeMay's

public reputation in tatters. LeMay was commonly assumed

to share Wallace's widely unpopular racist views, even

though LeMay had enthusiastically supported racial integration

in the US military publicly and privately. He fought segregation

in the Air Force before Executive Order 9981 systemically

banned the practice.

LeMay

and UFOs

The

April 25, 1988, issue of The New Yorker carried an interview

with retired Air Force Reserve Major General and former

US Senator from Arizona Barry Goldwater, who said he repeatedly

asked his friend General LeMay if he (Goldwater) might

have access to the secret "Blue Room" at Wright

Patterson Air Force Base, alleged by numerous Goldwater

constituents to contain UFO evidence. According to Goldwater,

an angry LeMay gave him "holy hell" and

said, "Not only can't you get into it but don't

you ever mention it to me again."

Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curtis_LeMay