General/Doctor

James Harold "Jimmy" Doolittle, USAF (December

14, 1896 – September 27, 1993) was an American aviation

pioneer. Doolittle served as an officer in the United

States Army Air Forces during the Second World War. He

earned the Medal of Honor for his valor and leadership

as commander of the Doolittle Raid while a lieutenant

colonel.

Early

life and education

Doolittle

was born in Alameda, California, and spent his youth in

Nome, Alaska, where he earned a reputation as a boxer.

His parents were Frank Henry Doolittle and Rosa (Rose)

Cerenah Shephard. By 1910, Jimmy Doolittle was attending

school in Los Angeles. When his school attended the 1910

Los Angeles International Air Meet at Dominguez Field

Doolittle saw his first airplane. He attended Los Angeles

City College after graduating from Manual Arts High School

in Los Angeles, and later won admission to the University

of California, Berkeley where he studied in The School

of Mines. He was a member of Theta Kappa Nu fraternity.

Doolittle took a leave of absence in October 1917 to enlist

in the Signal Corps Reserve as a flying cadet; he ground

trained at the School of Military Aeronautics (an army

school) on the campus of the University of California,

and flight-trained at Rockwell Field, California. Doolittle

received his Reserve Military Aviator rating and was commissioned

a first lieutenant in the Signal Officers Reserve Corps

on March 11, 1918.

Military

career

During

World War I, Doolittle stayed in the United States as

a flight instructor and performed his war service at Camp

John Dick Aviation Concentration Center ("Camp Dick"),

Texas; Wright Field, Ohio; Gerstner Field, Louisiana;

Rockwell Field, California; Kelly Field, Texas and Eagle

Pass, Texas.

Doolittle on his Curtiss R3C-2 Racer, the plane in which

he won the 1925 Schneider Trophy Race

Doolittle's

service at Rockwell Field consisted of duty as a flight

leader and gunnery instructor. At Kelly Field, he served

with the 104th Aero Squadron and with the 90th Aero Squadron

of the 1st Surveillance Group. His detachment of the 90th

Aero Squadron was based at Eagle Pass, patrolling the

Mexican border. Recommended by three officers for retention

in the Air Service during demobilization at the end of

the war, Doolittle qualified by examination and received

a Regular Army commission as a 1st Lieutenant, Air Service,

on July 1, 1920.

On

May 10, 1921, he was engineering officer and pilot for

an expedition recovering a plane that had force-landed

in a Mexican canyon on February 10 during a transcontinental

flight attempt by Lieut. Alexander Pearson. Doolittle

reached the plane on May 3 and found it serviceable, then

returned May 8 with a replacement motor and four mechanics.

The oil pressure of the new motor was inadequate and Doolittle

requested two pressure gauges, using carrier pigeons to

communicate. The additional parts were dropped by air

and installed, and Doolittle flew the plane to Del Rio,

Texas himself, taking off from a 400-yard airstrip hacked

out of the canyon floor.

Subsequently,

he attended the Air Service Mechanical School at Kelly

Field and the Aeronautical Engineering Course at McCook

Field, Ohio. Having at last returned to complete his college

degree, he earned the Bachelor of Arts from the University

of California, Berkeley in 1922, and joined the Lambda

Chi Alpha Fraternity.

Doolittle

was one of the most famous pilots during the inter-war

period. In September 1922, he made the first of many pioneering

flights, flying a de Havilland DH-4 – which was equipped

with early navigational instruments – in the first

cross-country flight, from Pablo Beach (renamed Jacksonville

Beach), Florida, to Rockwell Field, San Diego, California,

in 21 hours and 19 minutes, making only one refueling

stop at Kelly Field. The U.S. Army awarded him the Distinguished

Flying Cross.

Within

days after the transcontinental flight, he was at the

Air Service Engineering School (a precursor to the Air

Force Institute of Technology) at McCook Field, Dayton,

Ohio. For Doolittle, the school assignment had special

significance: "In the early '20s, there was not complete

support between the flyers and the engineers. The pilots

thought the engineers were a group of people who zipped

slide rules back and forth, came out with erroneous results

and bad aircraft; and the engineers thought the pilots

were crazy – otherwise they wouldn't be pilots. So

some of us who had had previous engineering training were

sent to the engineering school at old McCook Field. ...

After a year's training there in practical aeronautical

engineering, some of us were sent on to MIT where we took

advanced degrees in aeronautical engineering. I believe

that the purpose was served, that there was thereafter

a better understanding between pilots and engineers."

In

July 1923, after serving as a test pilot and aeronautical

engineer at McCook Field, Doolittle entered the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology. In March 1924, he conducted aircraft

acceleration tests at McCook Field, which became the basis

of his master's thesis and led to his second Distinguished

Flying Cross. He received his S.M. in Aeronautics from

MIT in June 1924. Because the Army had given him two years

to get his degree and he had done it in just one, he immediately

started working on his Sc.D. in Aeronautics, which he

received in June 1925. He said that he considered his

master's work more significant than his doctorate.

Following

graduation, Doolittle attended special training in high-speed

seaplanes at Naval Air Station Anacostia in Washington,

D.C.. He also served with the Naval Test Board at Mitchel

Field, Long Island, New York, and was a familiar figure

in air speed record attempts in the New York area. He

won the Schneider Cup race in a Curtiss R3C in 1925 with

an average speed of 232 MPH. For that feat, Doolittle

was awarded the Mackay Trophy in 1926.

Doolittle

in a pre-World War II photo

In

April 1926, Doolittle was given a leave of absence to

go to South America to perform demonstration flights.

In Chile, he broke both ankles, but put his P-1 Hawk through

aerial maneuvers with his ankles in casts. He returned

to the United States, and was confined to Walter Reed

Army Hospital for his injuries until April 1927. Doolittle

was then assigned to McCook Field for experimental work,

with additional duty as an instructor pilot to the 385th

Bomb Squadron of the Air Corps Reserve. During this time,

in 1927 he was the first to perform an outside loop previously

thought to be a fatal maneuver. Carried out in a Curtiss

fighter at Wright Field in Ohio, Doolittle executed the

dive from 10,000 feet, reached 280 miles per hour, bottomed

out upside down, then climbed and completed the loop.

Instrument

flight

Doolittle's

most important contribution to aeronautical technology

was the development of instrument flying. He was the first

to recognize that true operational freedom in the air

could not be achieved unless pilots developed the ability

to control and navigate aircraft in flight, from takeoff

run to landing rollout, regardless of the range of vision

from the cockpit. Doolittle was the first to envision

that a pilot could be trained to use instruments to fly

through fog, clouds, precipitation of all forms, darkness,

or any other impediment to visibility; and in spite of

the pilot's own possibly confused motion sense inputs.

Even at this early stage, the ability to control aircraft

was getting beyond the motion sense capability of the

pilot. That is, as aircraft became faster and more maneuverable,

pilots could become seriously disoriented without visual

cues from outside the cockpit, because aircraft could

move in ways that pilots' senses could not accurately

decipher.

Doolittle

was also the first to recognize these psycho-physiological

limitations of the human senses (particularly the motion

sense inputs, i.e., up, down, left, right). He initiated

the study of the subtle interrelationships between the

psychological effects of visual cues and motion senses.

His research resulted in programs that trained pilots

to read and understand navigational instruments. A pilot

learned to "trust his instruments," not his

senses, as visual cues and his motion sense inputs (what

he sensed and "felt") could be incorrect or

unreliable.

In

1929, he became the first pilot to take off, fly and land

an airplane using instruments alone, without a view outside

the cockpit. Having returned to Mitchel Field that September,

he assisted in the development of fog flying equipment.

He helped develop, and was then the first to test, the

now universally used artificial horizon and directional

gyroscope. He attracted wide newspaper attention with

this feat of "blind" flying and later received

the Harmon Trophy for conducting the experiments. These

accomplishments made all-weather airline operations practical.

In

January 1930, he advised the Army on the building of Floyd

Bennett Field in New York City. Doolittle resigned his

regular commission on February 15, 1930, and was commissioned

a major in the Air Reserve Corps a month later, being

named manager of the Aviation Department of Shell Oil

Company, in which capacity he conducted numerous aviation

tests. While in the Reserve, he also returned to temporary

active duty with the Army frequently to conduct tests.

Doolittle

helped influence Shell Oil Company to produce the first

quantities of 100 octane aviation gasoline. High octane

fuel was crucial to the high-performance planes that were

developed in the late 1930s.

In

1931, Doolittle won the Bendix Trophy Race from Burbank,

California, to Cleveland, Ohio, in a Laird Super Solution

biplane.

In

1932, Doolittle set the world's high speed record for

land planes at 296 miles per hour in the Shell Speed Dash.

Later, he took the Thompson Trophy Race at Cleveland in

the notorious Gee Bee R-1 racer with a speed averaging

252 miles per hour. After having won the three big air

racing trophies of the time, the Schneider, Bendix, and

Thompson, he officially retired from air racing stating,

"I have yet to hear anyone engaged in this work dying

of old age."

In

April 1934, Doolittle became a member of the Baker Board.

Chaired by former Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, the

board was convened during the Air Mail scandal to study

Air Corps organization. A year later, Doolittle transferred

to the Air Corps Reserve. In 1940, he became president

of the Institute of Aeronautical Science.

Doolittle

returned to active duty on July 1, 1940 with rank of Major.

He was assigned as the assistant district supervisor of

the Central Air Corps Procurement District at Indianapolis,

Indiana, and Detroit, Michigan, where he worked with large

auto manufacturers on the conversion of their plants for

production of planes. The following August, he went to

England as a member of a special mission and brought back

information about other countries' air forces and military

build-ups.

The

Doolittle Raid

Doolittle

was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel on January 2, 1942,

and assigned to Army Air Forces Headquarters to plan the

first retaliatory air raid on the Japanese homeland. He

volunteered for and received General H.H. Arnold's approval

to lead the top-secret attack of 16 B-25 medium bombers

from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, with targets in

Tokyo, Kobe, Yokohama, Osaka, and Nagoya. After training

at Eglin Field and Wagner Field in northwest Florida,

Doolittle, his aircraft and flight crews proceeded to

the McClellan Field, California for aircraft modifications

at the Sacramento Air Depot, followed by a short final

flight to Naval Air Station Alameda, California for embarkation

aboard USS Hornet. On April 18, all the bombers successfully

took off from the Hornet, reached Japan, and bombed their

targets. Fifteen of the planes then headed for their recovery

airfield in China, while one crew chose to land in Russia

due to their bomber's unusually high fuel consumption.

As did most of the other crewmen who participated in the

mission, Doolittle's crew bailed out safely over China

when their bomber ran out of fuel. By then they had been

flying for about 12 hours, it was nighttime, the weather

was stormy, and Doolittle was unable to locate their landing

field. Doolittle came down in a rice paddy (saving a previously

injured ankle from breaking) near Chuchow (Quzhou). He

and his crew linked up after the bailout and were helped

through Japanese lines by Chinese guerrillas and American

missionary John Birch. Other aircrews were not so fortunate.

Although most eventually reached safety with the help

of friendly Chinese, four crewmembers lost their lives

as a result of being captured by the Japanese and three

due to aircraft crash and/or while parachuting. Doolittle

went on to fly more combat missions as commander of the

12th Air Force in North Africa, for which he was awarded

four Air Medals. The other surviving members of the raid

also went on to new assignments.

Doolittle

received the Medal of Honor from President Franklin D.

Roosevelt at the White House for planning and leading

his raid on Japan. His citation reads: "For conspicuous

leadership above and beyond the call of duty, involving

personal valor and intrepidity at an extreme hazard to

life. With the apparent certainty of being forced to land

in enemy territory or to perish at sea, Lt. Col. Doolittle

personally led a squadron of Army bombers, manned by volunteer

crews, in a highly destructive raid on the Japanese mainland."

Lt Col James H. Doolittle, USAAF (front), leader of the

raiding force,

wires a Japanese medal to a 500-pound bomb, during ceremonies

on the

flight deck of USS Hornet (CV-8), shortly before his force

of sixteen B-25B

bombers took off for Japan. The planes were launched on

April 18, 1942.

The

Doolittle Raid is viewed by historians as a major morale-building

victory for the United States. Although the damage done

to Japanese war industry was minor, the raid showed the

Japanese that their homeland was vulnerable to air attack,

and forced them to withdraw several front-line fighter

units from Pacific war zones for homeland defense. More

significantly, Japanese commanders considered the raid

deeply embarrassing, and their attempt to close the perceived

gap in their Pacific defense perimeter led directly to

the decisive American victory during the Battle of Midway

in June 1942.

When

asked from where the Tokyo raid was launched, President

Roosevelt coyly said its base was Shangri-La, a fictional

paradise from the popular novel Lost Horizon. In the same

vein, the US Navy named one of its carriers the USS Shangri-La.

World

War II, post-raid

In

July 1942, as a Brigadier General – he had been promoted

by two grades on the day after the Tokyo attack, by-passing

the rank of full colonel – Doolittle was assigned

to the nascent Eighth Air Force and in September became

commanding general of the Twelfth Air Force in North Africa.

He was promoted to Major General in November 1942, and

in March 1943 became commanding general of the Northwest

African Strategic Air Forces, a unified command of U.S.

Army Air Force and Royal Air Force units.

Maj.

Gen. Doolittle took command of the Fifteenth Air Force

in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations in November

1943. On June 10, he flew as co-pilot with Jack Sims,

fellow Tokyo Raider, in a B-26 Marauder of the 320th Bombardment

Group, 442nd Bombardment Squadron on a mission to attack

gun emplacements at Pantelleria. Doolittle continued to

fly, despite the risk of capture, while being privy to

the Ultra secret, which was that the German encryption

systems had been broken by the British. From January 1944

to September 1945, he held his largest command, the Eighth

Air Force (8 AF) in England as a Lieutenant General, his

promotion date being March 13, 1944 and the highest rank

ever held by a reserve officer in modern times. Doolittle's

major influence on the European air war occurred early

in the year when he changed the policy requiring escorting

fighters to remain with the bombers at all times. With

his permission, P-38s, P-47s, and P-51s on escort missions

strafed German airfields and transport while returning

to base, contributing significantly to the achievement

of air supremacy by Allied Air Forces over Europe.

Lt Gen Jimmy Doolittle with Maj Gen Curtis LeMay standing

in front of a Lockheed P-38 Lightning in Britain, 1944.

After

the end of the European war, the Eighth Air Force was

re-equipped with B-29 Superfortress bombers and started

to relocate to Okinawa in the Pacific. Two bomb groups

had begun to arrive on August 7. However, the 8th was

not scheduled to be at full strength until February 1946

and Doolittle declined to rush 8th Air Force units into

combat saying that "If the war is over, I will not

risk one airplane nor a single bomber crew member just

to be able to say the 8th Air Force had operated against

the Japanese in the Pacific".

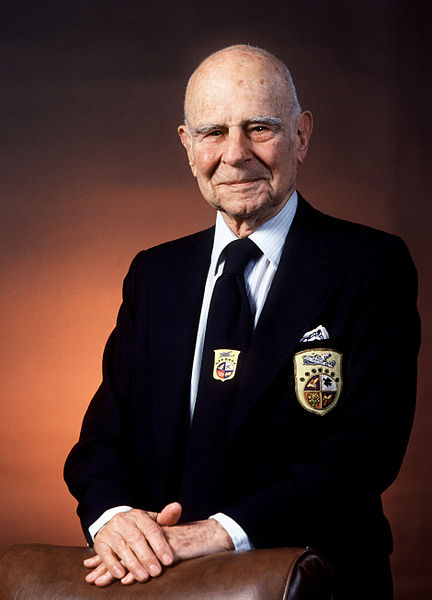

Personalized

photo of General Jimmy Doolittle.

Postwar

On

May 10, 1946, Doolittle reverted to inactive reserve status

at the grade of lieutenant general, a rarity in those

days when nearly all other reserve officers were limited

to the rank of major general or rear admiral, a restriction

that would not end in the US armed forces until the 21st

century. Doolittle returned to Shell Oil as a vice president,

and later as a director.

In

the summer of 1946 Doolittle went to Stockholm where he

was consulted about the "ghost rockets" than

had been observed over Scandinavia.

In

1947, Doolittle also became the first president of the

Air Force Association, an organization which he helped

create.

In

March 1951, Doolittle was appointed a special assistant

to the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, serving as a civilian

in scientific matters which led to Air Force ballistic

missile and space programs. In 1952, following a string

of three air crashes in two months at Elizabeth, New Jersey,

the President of the United States, Harry S. Truman, appointed

him to lead a presidential commission examining the safety

of urban airports. The report "Airports And Their

Neighbours" led to zoning requirements for buildings

near approaches, early noise control requirements, and

initial work on "super airports" with 10,000

ft runways, suited to 150 ton aircraft.

In

1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower asked Doolittle to

perform a study of the Central Intelligence Agency; The

resulting work was known as the Doolittle Report, 1954,

and was classified for a number of years.

Doolittle

retired from Air Force duty on February 28, 1959. He remained

active in other capacities, including chairman of the

board of TRW Space Technology Laboratories.

In

the mid-1960s, Doolittle visited South Africa and praised

the system of apartheid.

In

1972, Doolittle received the Tony Jannus Award for his

distinguished contributions to commercial aviation, in

recognition of the development of instrument flight.

On

April 4, 1985, the U.S. Congress promoted Doolittle to

the rank of full General on the Air Force retired list.

In a later ceremony, President Ronald Reagan and U.S.

Senator and retired Air Force Reserve Major General Barry

Goldwater pinned on Doolittle's four-star insignia.

Doolittle

is awarded a fourth star, pinned on by President Ronald

Reagan (left)

and Senator Barry Goldwater (right), April 10, 1985.

In

addition to his Medal of Honor for the Tokyo raid, Doolittle

also received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, two Distinguished

Service Medals, the Silver Star, three Distinguished Flying

Crosses, the Bronze Star, four Air Medals, and decorations

from Great Britain, France, Belgium, Poland, China, and

Ecuador. He is the only person to be awarded both the

Medal of Honor and the Medal of Freedom, the nation's

two highest honors. Doolittle was awarded the Public Welfare

Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 1959. In

1983, he was awarded the United States Military Academy's

Sylvanus Thayer Award. He was inducted in the Motorsports

Hall of Fame of America as the only member of the air

racing category in the inaugural class of 1989, and into

the Aerospace Walk of Honor in the inaugural class of

1990. The headquarters of the United States Air Force

Academy Association of Graduates (AOG) on the grounds

of the United States Air Force Academy, Doolittle Hall,

is named in his honor.

On

May 9, 2007, the new 12th Air Force Combined Air Operations

Center (CAOC), Building 74, at Davis-Monthan Air Force

Base in Tucson, Arizona, was named in his honor as the

"General James H. Doolittle Center." Several

surviving members of the Doolittle Raid were in attendance

during the ribbon cutting ceremony.

Personal

life

Doolittle

married Josephine "Joe" E. Daniels on December

24, 1917. At a dinner celebration after Jimmy Doolittle's

first all-instrument flight in 1929, Josephine Doolittle

asked her guests to sign her white damask tablecloth.

Later, she embroidered the names in black. She continued

this tradition, collecting hundreds of signatures from

the aviation world. The tablecloth was donated to the

Smithsonian Institution. Married for over 70 years, Josephine

Doolittle died in 1988, five years before her husband.

The

Doolittles had two sons, James Jr., and John. Both became

military aviators. James Jr. was an A-26 Invader pilot

during World War II and committed suicide at the age of

thirty-eight in 1958. At the time of his death, James

Jr. was a Major and commander of the 524th Fighter-Bomber

Squadron, piloting the F-101 Voodoo.

His

other son, John P. Doolittle, retired from the Air Force

as a Colonel, and his grandson, Colonel James H. Doolittle,

III, was the vice commander of the Air Force Flight Test

Center at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

Doolittle

photographed in 1986.

James

H. "Jimmy" Doolittle died at the age of 96 in

Pebble Beach, California on September 27, 1993, and is

buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, near

Washington, D.C., next to his wife. In his honor at the

funeral, there was also a flyover of Miss Mitchell, a

lone B-25 Mitchell, and USAF Eighth Air Force bombers

from Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. After a brief

graveside service, Doolittle's great-grandson played Taps

flawlessly.

Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jimmy_Doolittle