Walter

Bedell "Beetle" Smith (5 October 1895 – 9

August 1961) was a senior U.S. Army general who served as

General Dwight D. Eisenhower's chief- of-staff at Allied

Forces Headquarters during the Tunisia Campaign and the

Allied invasion of Italy in 1943. Beginning in the next

year, he was General Eisenhower's chief-of-staff at the

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF)

in Western Europe from 1944 through 1945.

Smith

enlisted as a private in the Indiana National Guard in

1911. During World War I he was commissioned as an officer

in 1917, and he was wounded in the Aisne-Marne Offensive

in 1918. After World War I, he was a staff officer and

an instructor at the U.S. Army Infantry School. In 1941,

he became the Secretary of the General Staff. Then in

1942, he became the Secretary to the Combined Chiefs of

Staff. His duties involved taking part in discussions

of war plans at the highest level, and Smith often briefed

President Franklin D. Roosevelt on strategic matters.

Smith

became chief of staff to Eisenhower at Allied Forces Headquarters

(AFHQ) in September 1942. He acquired a reputation as

Eisenhower's "hatchet man" for his brusque and

demanding manner. However, he was also capable of representing

Eisenhower in sensitive missions requiring diplomatic

skill. Smith was involved in negotiating the Armistice

between Italy and Allied armed forces, which he signed

on behalf of Eisenhower. In 1944, he became the Chief

of Staff of SHAEF, again under Eisenhower.

In

this position, Smith also negotiated successfully for

food and fuel aid to be sent through German lines for

the starving and cold Dutch civilian population, and he

opened discussions for the peaceful and complete German

capitulation to the Canadian Army in the Netherlands.

In May 1945, Smith met with the representatives of the

German High Command to negotiate the surrender of the

German Armed Forces, and he signed the surrender document

on behalf of General Eisenhower.

After

World War II, he served as the U.S. Ambassador to the

Soviet Union from 1946 to 1948. Then in 1950, Smith became

the Director of Central Intelligence, the head of the

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and other intelligence

agencies in the U.S. Smith reorganized the CIA, redefined

its structure and its mission, and he gave it a new sense

of purpose. He made the CIA the arm of government primarily

responsible for covert operations. He left the CIA in

1953 to become the Under Secretary of State. After retiring

as the Under Secretary of State in 1954, Smith continued

to serve the Eisenhower Administration in various posts

for several years, until his retirement and his death

in 1961.

United States Ambassador to Soviet Union

Early

life

Walter

Bedell Smith was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, on October

5, 1895, the eldest of two sons of William Long Smith,

a silk buyer for the Pettis Dry Goods Company, and his

wife, Ida Francis née Bedell, who worked for the

same company.

Smith

was called Bedell from his boyhood. From an early age

he was nicknamed "Beetle", or occasionally "Beedle"

or "Boodle". He was educated at St. Peter and

Paul School, public schools #10 and #29, Oliver Perry

Morton School, and Emmerich Manual High School, where

he studied to be a machinist. While still there, he took

a job at the National Motor Vehicle Company, and eventually

left high school without graduating. Smith enrolled at

Butler University, but his father developed serious health

problems, and Smith left university to return to his job

and support his family.

In

1911, at the age of 16, Smith enlisted as a private in

Company D of the 2nd Indiana Infantry of the Indiana National

Guard. The Indiana National Guard was called out twice

in 1913, for the Ohio River flood of 1913 and during a

streetcar strike. Smith was promoted to corporal and then

sergeant. During the Pancho Villa Expedition he served

on the staff of the Indiana National Guard.

In

1913, Smith met Mary Eleanor (Nory) Cline, and they were

married in a traditional Roman Catholic wedding ceremony

on July 1, 1917. Their marriage was of long duration but

the Smiths did not have any children.

World

War I

Smith's

work during the Ohio River flood of 1913 led to his nomination

for officer training in 1917, and he was sent to the Officer

Candidate Training Camp at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana.

Upon his graduation on November 27, 1917, he was commissioned

as a second lieutenant. He was then assigned to the newly

formed Company A, 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry, part of

the 4th Infantry Division at Camp Greene, North Carolina.

The 4th Infantry Division embarked for Europe, then embroiled

in World War I, from Hoboken, New Jersey, on 9 May 1918,

reaching Brest, France, on the 23rd of May.

After

training with the British and French Armies, the 4th Division

entered the front lines in June 1918, joining the Aisne-Marne

Offensive on 18 July 1918. Smith was wounded by shell

fragments during an attack two days later.

Because

of his wounds, Smith was returned to the United States

for service with the U.S. Department of War's General

Staff, and he was assigned to the Military Intelligence

Division. In September 1918, he was commissioned as a

first lieutenant in the regular army of the United States.

Smith

was next sent to the newly formed 379th Infantry Regiment

as its intelligence officer. This regiment was part of

the 95th Infantry Division, based at Camp Sherman, Ohio.

The 95th Infantry Division was disbanded following the

signing of the Armistice with Germany on November 11,

1918.

Then

in February 1919 Smith was assigned to Camp Dodge, Iowa,

where he was involved with the disposal of surplus equipment

and supplies. In March 1919 he was transferred to the

2nd Infantry Regiment, a regular unit based at Camp Dodge,

remaining there until November 1919, when it moved to

Camp Sherman.

Between

the wars

The

staff of the 2nd Infantry moved to Fort Sheridan, Illinois,

in 1921. In 1922, Smith became aide de camp to Brigadier

General George Van Horn Moseley, the commander of the

12th Infantry Brigade at Fort Sheridan. From 1925 to 1929

Smith worked as an assistant in the Bureau of the Budget.

He then served a two-year tour of duty overseas on the

staff of the 45th Infantry at Fort William McKinley in

the Philippines. After nine years as a first lieutenant,

he was promoted to captain in September 1929.

Returning

to the United States, Smith reported to the U.S. Army

Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia, in March 1931.

Upon graduation in June 1932, he stayed on as an instructor

in the Weapons Section, where he was responsible for demonstrating

weapons like the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle. In 1933

he was sent to the Command and General Staff School at

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Afterward, he returned to the

Infantry School but was detached again to attend the U.S.

Army War College, from which he graduated in 1937. He

returned to the Infantry School once more, where he was

promoted to major on 1 January 1939 after nine years as

a captain. Such slow promotion was common in the Army

in the 1920s and 1930s. Officers like Smith who were commissioned

between November 1916 and November 1918 made up 55.6 percent

of the Army's officer corps in 1926. Promotions were usually

based on seniority, and the modest objective of promoting

officers to major after seventeen years of service could

not be met because a shortage of posts for them to fill.

World

War II

Washington

When

General George C. Marshall became the Army's Chief of

Staff in September 1939, he brought Smith to Washington,

D.C., to be the Assistant to the Secretary of the General

Staff. The Secretary of the General Staff was primarily

concerned with records, paperwork, and the collection

of statistics, but he also performed a great deal of analysis,

liaison, and administration. One of Smith's duties was

liaison with Major General Edwin "Pa" Watson,

the Senior Military Aide to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Smith was promoted to lieutenant colonel on 4 May 1941,

and then to colonel on 30 August 1941. On 1 September,

the Secretary of the General Staff, Colonel Orlando Ward,

was given command of the 1st Armored Division, and Smith

became the Secretary of the General Staff.

The

Arcadia Conference, which was held in Washington, D.C.,

December 1941 and January 1942, mandated the creation

of the Joint Chiefs of Staff as a counterpart to the British

Chiefs of Staff Committee, and Smith was named as its

secretary on 23 January 1942. The same conference also

brought about the creation of the Combined Chiefs of Staff,

which consisted of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Chiefs

of Staff Committee meeting as a single body. Brigadier

Vivian Dykes of the British Joint Staff Mission provided

the secretarial arrangements for the new organization

at first, but General Marshall thought that an American

secretariat was required. He appointed Smith as the secretary

of the Combined Chiefs-of-Staff as well as of the Joint

Chiefs-of-Staff. Since Dykes was senior in service time

to Smith, and Marshall wanted Smith to be in charge, Smith

was promoted to brigadier general on 2 February 1942.

He assumed the new post a week later, with Dykes as his

deputy. The two men worked in partnership to create and

organize the secretariat, and to build the organization

of the Combined Chiefs-of-Staff into one that could coordinate

the war efforts of the two allies, along with the Canadians,

Australians, French, etc. Smith's duties involved taking

part in discussions of strategy at the highest level,

and he often briefed President Roosevelt on strategic

matters. However Smith became frustrated as he watched

other officers receive the operational commands that he

desired. He later remarked: "That year I spent working

as secretary of the general staff for George Marshall

was one of the most rewarding of my entire career, and

the unhappiest year of my life."

North

African Theater

When

Major General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed as the

commander of the European Theater of Operations in June

1942, he requested that Smith be sent from Washington

as his chief-of-staff. Smith's record as a staff officer,

and his proven ability to work harmoniously with the British,

made him a natural choice for the post. Reluctantly, Marshall

acceded to this request, and Smith took over as the chief-of-staff

at Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) on 15 September 1942.

Reporting to him were two deputy chiefs of staff, Brigadier

General Alfred Gruenther and Brigadier John Whiteley,

and also the Chief Administrative Officer (CAO), Major

General Humfrey Gale. AFHQ was a balanced binational organization,

in which the chief of each section was paired with a deputy

of the other nationality. Its structure was generally

American, but with some British aspects. For example,

Gale as CAO controlled both personnel and supply functions,

which under the American system would have reported directly

to Smith. Initially AFHQ was located in London, but it

was moved to Algiers during November and December 1942,

with Smith arriving on 11 December. Although AFHQ had

an authorized strength of only 700, Smith aggressively

expanded it. By January 1943, its American component alone

was 1,406 and its strength eventually topped 4,000 men

and women. As the chief-of-staff, Smith zealously guarded

access to Eisenhower. He acquired a reputation as a tough

and brusque manager, and he was often referred to as Eisenhower's

"hatchet man".

Pending

the organization of the North African Theater of Operations,

U.S. Army (NATOUSA), Smith also acted as its chief- of-staff

until 15 February, when Brigadier General Everett S. Hughes

became the Deputy Theater commander and the commanding

general of the Communications Zone. The relationship between

Smith and Hughes, an old friend of Eisenhower's, was tense,

with Smith accusing Hughes of "empire building",

and the two clashing over trivial issues.

In

Algiers Smith and Eisenhower seldom socialized together.

Smith conducted formal dinners at his villa, an estate

surrounded by gardens and terraces, with two large drawing

rooms decorated with mosaics, oriental rugs, and art treasures.

Like Eisenhower, Smith had a female companion, a nurse,

Captain Ethel Westerman.

Following

the disastrous Battle of the Kasserine Pass, Eisenhower

sent Smith forward to report on the state of affairs at

the American II Corps. Smith recommended the relief of

its commander, Major General Lloyd Fredendall, as did

General Harold Alexander and Major Generals Omar Bradley

and Lucian Truscott. On their advice, Eisenhower replaced

Fredendall with Major General George S. Patton, Jr. Eisenhower

also relieved his Assistant Chief of Staff Intelligence

(G-2), Brigadier Eric Mockler-Ferryman, pinpointing faulty

intelligence at AFHQ as a contributing factor in the defeat

at Kasserine. Mockler-Ferryman was replaced by Brigadier

Kenneth Strong.

The

debacle at Kasserine Pass strained relations between the

Allies, and another crisis developed when II Corps reported

that enemy aviation was operating at will over its sector

because of an absence of Allied air cover. This elicited

a scathing response from British Air Marshal Arthur Coningham

on the competence of American troops.

General

Eisenhower drafted a letter to Marshall suggesting that

Coningham should be relieved of his command since he could

not control the acrimony between senior Allied commanders,

but General Smith persuaded him not to send it.[36] Instead,

Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, Major General Carl Spaatz,

and Brigadier General Laurence S. Kuter paid Patton a

visit at his headquarters. Their meeting was interrupted

by a German air raid that convinced the airmen that General

Patton had a point. Coningham withdrew his written criticisms

and he apologized.

Allied leaders in the Sicilian campaign. General Eisenhower

meets in North Africa with (foreground, left to right):

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder, General Sir Harold

R.L.G. Alexander, Admiral Sir Andrew B. Cunningham,

and (top row): Mr. Harold Macmillan, Major General W.

Bedell Smith, and several unidentified British officers.

For

the Allied invasion of Sicily, the Combined Chiefs of

Staff designated Eisenhower as the overall commander but

they ordered the three component commanders, Alexander,

Tedder, and Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham of the Royal

Navy, to "cooperate". To Eisenhower, this command

arrangement meant a reversion to the old British "committee

system". He drafted a cable to the Combined Chiefs-of-Staff

demanding a unified command structure, but Smith persuaded

him to tear it up.

Disagreements

arose between Allied commanders over the operational plan,

which called for a series of dispersed landings, based

on the desire of the air, naval, and logistical planners

concerning the early capture of ports and airfields. General

Bernard Montgomery, the commander of the British Eighth

Army, objected to this aspect of the plan, since it exposed

the Allied forces to defeat in detail.

Montgomery

put forward an alternate plan that involved the American

and British forces landing side by side. He convinced

Smith that his alternate plan was sound, and the two men

then persuaded most of the other Allied commanders. Montgomery's

plan provided for the early seizure of airfields, which

satisfied Tedder and Cunningham. The fears of logisticians

like Major General Thomas B. Larkin that supply would

not be practical without a port were resolved by the use

of amphibious trucks.

In

August 1943, Smith and Strong flew to Lisbon via Gibraltar

in civilian clothes, where they met with Generale di Brigata

Giuseppe Castellano at the British embassy. While Castellano

had hoped to arrange terms for Italy to join the United

Nations against Nazi Germany, Smith was empowered to draw

up an armistice between Italy and Allied armed forces,

but he was unable to negotiate political matters. On September

3, Smith and Castellano signed the agreed-upon text on

behalf of Eisenhower and Pietro Badoglio, respectively,

in a simple ceremony beneath an olive tree at Cassibile,

Sicily.

Secret Emissaries to Lisbon (left to right) Brigadier

Kenneth W. D. Strong, Generale di Brigata

Giuseppe Castellano, Smith, and Consul Franco Montanari,

an official from the Italian Foreign Office.

Then

in October, Smith traveled to Washington for two weeks

to represent Eisenhower in a series of meetings, including

one with President Roosevelt at Hyde Park, New York, on

10 October.

European

Theater

In

December 1943, Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Allied

Commander for Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy.

Eisenhower wished to take Smith and other key members

of his AFHQ staff with him to his new assignment, but

Prime Minister Winston Churchill wanted to retain Smith

at AFHQ as Deputy Supreme Commander in the Mediterranean.

Churchill reluctantly gave way at Eisenhower's insistence.

On

New Year's Eve, Smith met with General Sir Alan Brooke

to discuss the transfer of key British staff members from

AFHQ to Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force

(SHAEF). Brooke released Gale only after a strong appeal

from Smith, and he refused to transfer Strong. A heated

exchange resulted, and Brooke later complained to Eisenhower

about Smith's behavior. This was the only time that a

senior British officer ever complained openly about Smith.

Whiteley

became Chief of Intelligence (G-2) at SHAEF instead of

Strong, but Eisenhower and Smith had their way in the

long run, and Strong assumed the post on 25 May 1944,

with Brigadier General Thomas J. Betts as his deputy.

Smith

was promoted to lieutenant general and also made a Knight

Commander of the Order of the Bath in January 1944. On

18 January, he set out for London with two and a half

tons of personal baggage loaded onto a pair of B-17s.

The staff of the Chief-of-Staff to the Supreme Allied

Commander (COSSAC) was already active, and he had been

planning the Overlord operation for some time.

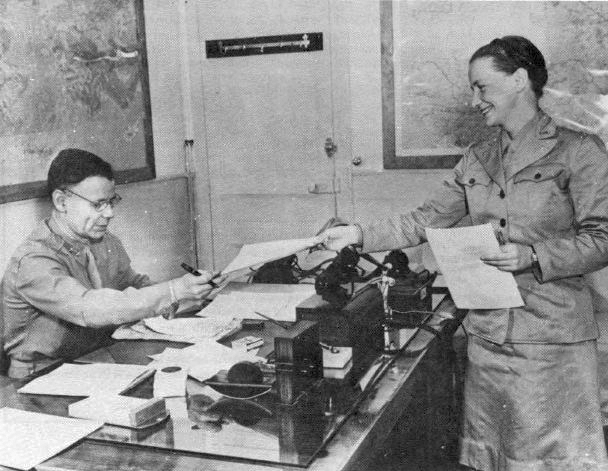

Smith and his wartime secretary, Ruth Briggs, who was

also Smith's executive

assistant when he was Ambassador to the Soviet Union after

the war

This

staff was absorbed into SHAEF, with COSSAC, with Major

General Frederick Morgan, becoming Smith's Deputy Chief

of Staff at SHAEF. Gale also held the title of Deputy

Chief of Staff, as well as being Chief Administrative

Officer, and there was also a Deputy Chief of Staff (Air),

Air Vice Marshal James Robb. The heads of the other staff

divisions were Major General Ray W. Barker (G-1), Major

General Harold R. Bull (G-3), Major General Robert W.

Crawford (G-4) and Major General Sir Roger Lumley (G-5).

Morgan

had located his COSSAC headquarters in Norfolk House at

31 St. James's Square, London, but Smith moved it to Bushy

Park on the outskirts of London. This was according to

Eisenhower's expressed desire not to have his headquarters

inside of a major city. A hutted camp was built with 130,000

square feet (12,000 m2) of floor space. By the time Overlord

began, accommodations had been provided for 750 officers

and 6,000 enlisted men and women.

Eisenhower

and Smith's offices were in a subterranean complex. Smith's

office was spartan, dominated by a large portrait of Marshall.

An advanced command post codenamed Sharpener was established

near Portsmouth, where Montgomery's 21st Army Group and

Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay's Allied Naval Expeditionary

Force headquarters were located.

Ground

operations in Normandy were controlled by Montgomery at

first, but SHAEF Forward headquarters moved to Jullouville

in August, and on 1 September Eisenhower assumed control

of Bradley's 12th Army Group and Montgomery's 21st Army

Group. Smith soon realized that he had made a mistake.

The forward headquarters was remote and inaccessible,

and it lacked the necessary communications equipment.

On

6 September, Eisenhower ordered both SHAEF Forward and

SHAEF Main to move to Versailles, France, as soon as possible.

SHAEF Forward began its move on 15 September and it opened

in Versailles on 20 September. SHAEF Main followed, moving

from Bushy Park by air. This move was completed by October,

and SHAEF remained there until 17 February 1945, when

SHAEF Forward moved to Reims. By this time, SHAEF had

grown in size to 16,000 officers and enlisted men, of

whom 10,000 were American and 6,000 British.

Meeting

of the Allied Supreme Command in February 1944. Left to

right: Lieutenant General Omar Bradley,

Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur

Tedder, General Dwight Eisenhower, General Sir

Bernard Montgomery, Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory

and Lieutenant General Bedell Smith.

By

November 1944, Strong was reporting that there was a possibility

of a German counteroffensive in the Ardennes or the Vosges.

Smith sent Strong to personally warn Bradley, who was

preparing an offensive of his own. The magnitude and ferocity

of the German Ardennes Offensive came as a shock, and

Smith had to defend Strong against criticism for failing

to sound the alarm. He felt that Strong had given ample

warning, which had been discounted or disregarded by himself

and others.

Once

battle was joined, Eisenhower acted decisively, committing

the two armored divisions in the 12th Army Group's reserve

over Bradley's objection, along with his own meager reserves,

two airborne divisions. Whiteley and Betts visited the

U.S. First Army headquarters and they were unimpressed

with the way its commanders were handling the situation.

Strong,

Whiteley, and Betts recommended that command of the armies

north of the Ardennes be transferred from Bradley to Montgomery.

Smith's immediate reaction was to dismiss the suggestion

out of hand. He told Strong and Whiteley that they were

fired and should pack their bags and return to the United

Kingdom. On the next morning, Smith apologized. He had

had second thoughts, and he informed them that he would

present their recommendation to Eisenhower as his own.

He realized the military and political implications of

this, and knew that such a recommendation had to come

from an American officer. On 20 December, he recommended

it to Eisenhower, who telephoned both General Bradley

and Montgomery, and Eisenhower ordered it.

This

decision was greatly resented by many Americans, particularly

in 12th Army Group, who felt that the action discredited

the U.S. Army's command structure.

Heavy

casualties since the start of Operation Overlord resulted

in a critical shortage of infantry replacements even before

the crisis situation created by the Ardennes Offensive.

Steps were taken to divert men from Communications Zone

units. The commander of the Communication Zone, Lieutenant

General John C. H. Lee, persuaded Eisenhower to allow

soldiers to volunteer for service "without regard

to color or race to the units where assistance is most

needed, and give you the opportunity of fighting shoulder

to shoulder to bring about victory". Smith immediately

grasped the political implications of this. He put his

position to Eisenhower in writing:

Although

I am now somewhat out of touch with the War Department's

Negro policy, I did, as you know, handle this during the

time I was with General Marshall. Unless there has been

a radical change, the sentence which I have marked in

the attached circular letter will place the War Department

in very grave difficulties. It is inevitable that this

statement will get out, and equally inevitable that the

result will be that every Negro organization, pressure

group and newspaper will take the attitude that, while

the War Department segregates colored troops into organizations

of their own against the desires and pleas of all the

Negro race, the Army is perfectly willing to put them

in the front lines mixed in units with white soldiers,

and have them do battle when an emergency arises. Two

years ago, I would have considered the marked statement

the most dangerous thing that I had ever seen in regard

to Negro relations. I have talked with Lee about it, and

he can't see this at all. He believes that it is right

that colored and white soldiers should be mixed in the

same company. With this belief I do not argue, but the

War Department policy is different. Since I am convinced

that this circular letter will have the most serious repercussions

in the United States, I believe that it is our duty to

draw the War Department's attention to the fact that this

statement has been made, to give them warning as to what

may happen and any facts which they may use to counter

the pressure which will undoubtedly be placed on them.

The

policy was revised, with Negro soldiers serving in provisional

platoons. In the 12th Army Group, these were attached

to regiments, while in the 6th Army Group, the platoons

were grouped into whole companies attached to the division.

The former arrangement were generally better rated by

the units they were attached to, because the Negro platoons

had no company-level unit training.

On

15 April 1945, the Nazi governor (Reichskommissar) of

the Netherlands, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, offered to open

up Amsterdam to food and coal shipments to ease the suffering

of the civilian population. Smith and Strong, representing

SHAEF, along with Major General Ivan Susloparov representing

the Soviet Union, Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld

representing the Dutch government, and Major General Sir

Francis de Guingand from 21st Army Group, met with Seyss-Inquart

in the Dutch village of Achterveld on 30 April. After

threatening Seyss-Inquart with prosecution for war crimes,

Smith successfully negotiated for the provision of food

to the suffering Dutch civilian population in the cities

in the west of the country, and he opened discussions

for the peaceful and complete German capitulation in the

Netherlands, to the Canadian Army, that did follow on

the 5th of May.

Smith

had to conduct another set of surrender negotiations,

that of the German armed forces, in May 1945. Smith met

with the representatives of the German High Command (the

Oberkommando der Wehrmacht), Colonel General Alfred Jodl

and General-Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg. Once again,

Strong acted as an interpretor. Smith took a hard line,

threatening that unless terms were accepted, the Allies

would seal the front, thus forcing the remaining Germans

into the hands of the Red Army, but he made some concessions

regarding a ceasefire before the surrender came into effect.

On May 7, Smith signed the surrender document, along with

the French representative, Major General François

Sevez, and the Soviet Susloparov.

Senior

Allied commanders at Rheims shortly after the German surrender.

Present are (left to right): Major General

Ivan Susloparov, Lieutenant General Frederick Morgan,

Lieutenant General Bedell Smith, Captain Kay Summersby

(obscured), Captain Harry C. Butcher, General of the Army

Dwight Eisenhower, Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder.

After

the war

Ambassador

to the Soviet Union

Smith

briefly returned to the United States in June 1945. In

August, Eisenhower nominated Smith as his successor as

commander of "U.S. Forces, European Theater",

as ETOUSA was redesignated on July 1, 1945. Smith was

passed over in favor of General Lucius D. Clay. When Eisenhower

took over as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army in November

1945, he summoned Smith to become his Assistant Chief

of Staff for Operations and Planning. However, soon after

his arrival back in Washington he was asked by President

Harry S. Truman and U.S Secretary of State James F. Byrnes

to become the U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union. In

putting Smith's nomination for the post before the U.S.

Congress, Truman asked for and received special legislation

permitting Smith to retain his permanent military rank

of major general.

Smith

as the U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, 1946–48

Smith's

service as the American ambassador was not a success.

Although no fault of Smith's, during his tenure the relationship

between the U.S. and the Soviet Union deteriorated rapidly

as the Cold War set in. Smith's tenacity of purpose came

across as a lack of flexibility, and it did nothing to

allay Soviet fears about American intentions. He became

thoroughly disillusioned and turned into a hardened cold

warrior who saw the Soviet Union as a secretive, totalitarian

and antagonistic state. In My Three Years in Moscow (1950),

Smith's account of his time as ambassador, he wrote:

... we are forced into a continuing struggle for a free

way of life that may extend over a period of many years.

We dare not allow ourselves any false sense of security.

We must anticipate that the Soviet tactic will be to wear

us down, to exasperate us, and to keep probing for weak

spots, and we must cultivate firmness and patience to

a degree we have never before required.

Very

prophetic words.

Smith

returned to the U.S. in March 1949. Truman offered him

the post of Assistant Secretary of State for European

Affairs but General Smith declined the appointment, preferring

to return to military duty. He was appointed as the commander

of U.S. First Army at Fort Jay, New York City. This position,

his first command since 1918, was an easy job for a generous

salary.

Throughout

the war, Smith had been troubled by a recurring stomach

ulcer. It became acute in 1949. He was no longer able

eat a normal diet, and he was suffering from malnutrition.

Smith was admitted to the Walter Reed Army Hospital, where

the surgeons decided to remove most of his stomach. This

did cure his ulcer, but Smith remained malnourished and

thin.

Director

of Central Intelligence

In

1950, Truman selected Smith as Director of Central Intelligence

(DCI), the head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Since the post had been established in 1946, there had

been three directors, none of whom had wanted the job.

The

1949 Intelligence Survey Group had produced the Dulles-Jackson-Correa

Report, which found that the CIA had failed in its responsibilities

in both the coordination and production of intelligence.

In response, the U.S. National Security Council accepted

the conclusions and recommendations of the report. It

remained to implement them. In May 1950, President Truman

decided that Smith was the man he needed for the CIA.[74]

Before Smith could assume the post on 7 October, there

was a major intelligence failure. The North Korean invasion

of South Korea in June 1950, which started the Korean

War, took the administration entirely by surprise, and

it raised fears of a third world war.

Since

Smith knew little about the Agency, he asked for a deputy

who did. Sidney Souers, the Executive Secretary of the

National Security Council, recommended William Harding

Jackson, one of the authors of the Dulles-Jackson-Correa

Report, to Smith. Jackson accepted the post of Deputy

Director on three conditions, one of which was "no

bawlings out".

Bedell

Smith (center) with top Agency leaders, including outgoing

D.C.I.

Hillenkoetter (to Smith’s left, in light suit), 7

October 1950

Smith

and Jackson moved to reorganize the agency in line with

the recommendations of the Dulles-Jackson-Correa Report.

They streamlined procedures for gathering and disseminating

intelligence. On 10 October, Smith was asked to prepare

estimates for the Wake Island Conference between the President

and General Douglas MacArthur. Smith insisted that the

estimates be simple, readable, conclusive, and useful

rather that mere background. They reflected the best information

available, but unfortunately, one estimate concluded that

the Chinese would not intervene in Korea, another major

intelligence failure.

Four

months after the outbreak of the Korean War, the Agency

had produced no coordinated estimate of the situation

in Korea. Smith created a new Office of National Estimates

(ONE) under the direction of William L. Langer, the Harvard

historian who had led the Research and Analysis branch

of the wartime Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Langer's

staff created procedures that were followed for the next

two decades. Smith stepped up efforts to obtain economic,

psychological, and photographic intelligence. By December

1, Smith had formed a Directorate for Administration.

The Agency would ultimately be divided by function into

three directorates: Administration, Plans, and Intelligence.

D.C.I.

Smith briefing President Truman

Smith

is remembered in the CIA as its first successful Director

of Central Intelligence, and one of its most effective,

who redefined its structure and mission. The CIA's expansive

covert action program remained the responsibility of Frank

Wisner's quasi-independent Office of Policy Coordination

(OPC), but Smith began to bring OPC under the DCI's control.

In early January 1951 he made Allen Dulles the first Deputy

Director for Plans (DDP), to supervise both OPC and the

CIA's separate espionage organization, the Office of Special

Operations (OSO). Not until January 1952 were all intelligence

functions consolidated under a Deputy Director for Intelligence

(DDI). Wisner succeeded Dulles as DDP in August 1951,

and it took until August 1952 to merge the OSO and the

OPC, each of which had its own culture, methods, and pay

scales, into an effective, single directorate.

By

consolidating responsibility for covert operations, Smith

made the CIA the arm of government primarily responsible

for them. Smith wanted the CIA to become a career service.

Before the war, the so-called "Manchu Law" limited

the duration of an officer's temporary assignments, which

effectively prevented anyone from making a career as a

general staff officer. There were no schools for intelligence

training, and the staffs had little to do in peacetime.

Career officers therefore tended to avoid such work unless

they aspired to be military attachés. Smith consolidated

training under a Director of Training and developed a

career service program.

When

Eisenhower was appointed as the Supreme Allied Commander

Europe in 1951, he asked for Smith to serve as his chief

of staff again. Truman turned down the request, stating

that the DCI was a more important post. Eisenhower therefore

took Lieutenant General Alfred Gruenther with him as his

chief of staff. When Eisenhower later recommended Gruenther's

elevation to four-star rank, Truman decided that General

Smith should be promoted also.

However,

Smith's name was omitted from the promotion list. Truman

then announced that no one would be promoted until Smith

was, which occurred on 1 August 1951. Smith retired from

the Army upon leaving the CIA on 9 February 1953.

Under

Secretary of State

On

11 January 1953, Eisenhower, now president-elect, announced

that Smith would become Under Secretary of State. Smith's

appointment was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on 6 February

and he resigned as the DCI three days later. In May 1954,

Smith traveled to Europe in an attempt to convince the

British to participate in an intervention to avert French

defeat in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. When this failed,

he reached an agreement with the Soviet Foreign Minister,

Vyacheslav Molotov, to partition Vietnam into two separate

states. In 1953, the President of Guatemala, Jacobo Árbenz

Guzmán, threatened to nationalize land belonging

to the United Fruit Company. Smith ordered the American

ambassador in Guatemala to put a CIA plan for a Guatemalan

coup into effect, which was accomplished by the following

year. Smith left the State Department on 1 October 1954

and took up a position with the United Fruit Company.

He also served as President and Chairman of the Board

of the Associated Missile Products Company and AMF Atomics

Incorporated, Vice Chairman of American Machine and Foundry

(AMF) and a director of RCA and Corning Incorporated.

After

retiring as Under Secretary of State in 1954, Smith continued

to serve the Eisenhower administration in various posts.

He was a member of the National Security Training Commission

from 1955 to 1957, the National War College board of consultants

from 1956 to 1959, the Office of Defense Mobilization

Special Stockpile Advisory Committee from 1957 to 1958,

the President's Citizen Advisors on the Mutual Security

Program from 1956 to 1957, and the President's Committee

on Disarmament in 1958. Smith was a consultant at the

Special Projects Office (Disarmament) in the Executive

Office of the President from 1955 to 1956. He also served

as Chairman of the Advisory Council of the President's

Committee on Fund Raising, and as a member-at-large from

1958 to 1961. In recognition of his other former boss,

he was a member of the George C. Marshall Foundation Advisory

Committee from 1960 to 1961.

Death

and legacy

In

1955, Smith was approached to perform the voice-over and

opening scene for the movie To Hell And Back (1955), which

was based on the autobiography of Audie Murphy. He accepted,

and had small parts in the movie, most notably in the

beginning, where he was dressed in his old service uniform.

He narrated several parts of the movie, referring constantly

to "the foot soldier". Smith was portrayed on

screen by Alexander Knox in The Longest Day (1962), Edward

Binns in Patton (1970) and Timothy Bottoms in Ike: Countdown

to D-Day (2004). On television he has been portrayed by

John Guerrasio in Cambridge Spies (2003), Charles Napier

in War and Remembrance (1989), Don Fellows in The Last

Days of Patton (1986) and J.D. Cannon in Ike: The War

Years (1979).

Smith

suffered a heart attack on August 9, 1961, at his home

in Washington, D.C., and he died in the ambulance on the

way to Walter Reed Army Hospital. Although entitled to

a Special Full Honor Funeral, at the request of his widow,

Mary Eleanor Smith, a simple joint service funeral was

held, patterned after the one given to General Marshall

in 1959. She selected a grave site for her husband in

Section 7 of Arlington National Cemetery close to Marshall's

grave. Mrs. Smith was buried next to him after her death

in 1963. Smith's papers are in the Eisenhower Presidential

Center in Abilene, Kansas.

Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Bedell_Smith