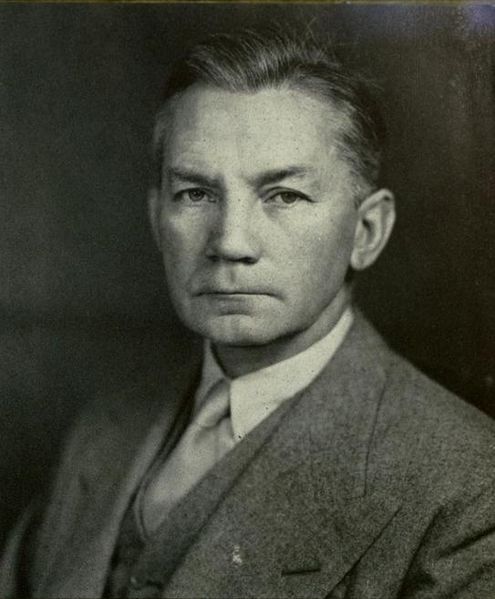

James

Vincent Forrestal (February 15, 1892 – May 22, 1949)

was the last Cabinet-level United States Secretary of

the Navy and the first United States Secretary of Defense.

1st United States Secretary of Defense

Forrestal

was a supporter of naval battle groups centered on aircraft

carriers. In 1954, the world's first supercarrier was

named USS Forrestal in his honor, as is the headquarters

of the United States Department of Energy. He is also

the namesake of the Forrestal Lecture Series at the United

States Naval Academy, which brings prominent military

and civilian leaders to speak to the Brigade of Midshipmen,

and of the James Forrestal Campus of Princeton University

in Plainsboro Township, New Jersey.

Early

life and private employment

Forrestal

was born in Matteawan, New York, (now part of Beacon,

New York), the youngest son of James Forrestal, an Irish

immigrant who dabbled in politics. His mother, the former

Mary Anne Toohey (herself the daughter of another Irish

immigrant) raised him as a devout Roman Catholic.[2] He

was an amateur boxer.[1] After graduating from high school

at the age of 16 in 1908, he spent the next three years

working for a trio of newspapers: the Matteawan Evening

Journal, the Mount Vernon Argus and the Poughkeepsie News

Press.

Forrestal

entered Dartmouth College in 1911, but transferred to

Princeton University sophomore year. He served as an editor

for The Daily Princetonian. The senior class voted him

"Most Likely to Succeed", but he left just prior

to completing work on a degree.

Forrestal

went to work as a bond salesman for William A. Read and

Company (later renamed Dillon, Read & Co.) in 1916

and, except for his service during World War I, remained

there until 1940. He became a partner (1923), vice-president

(1926), and president of the company (1937).

When

World War I broke out, he enlisted in the Navy and ultimately

became a Naval Aviator, training with the Royal Flying

Corps in Canada. During the final year of the war, Forrestal

spent much of his time in Washington, D.C., at the office

of Naval Operations, while completing his flight training.

He eventually reached the rank of Lieutenant.

Following

the war, Forrestal served as a publicist for the Democratic

Party committee in Dutchess County, New York helping politicians

from the area win elections at both the state and national

level. One of those individuals aided by his work was

a neighbor, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

By

some accounts, Forrestal was a compulsive workaholic,

skilled administrator, pugnacious, introspective, shy,

philosophic, solitary, and emotionally insecure.

He

married Mrs. Josephine Stovall (born Ogden), a Vogue writer,

in 1926. She eventually developed alcohol and mental problems.

Political

career

Secretary

of the Navy

President

Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Forrestal a special administrative

assistant on June 22, 1940. Six weeks later, he nominated

him for the newly established position, Undersecretary

of the Navy. In his nearly four years as undersecretary,

Forrestal proved highly effective at mobilizing domestic

industrial production for the war effort. Chief of Naval

Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King, wanted to control

logistics and procurement, but Forrestal prevailed.

In

September 1942, to get a grasp on the reports for material

his office was receiving, he made a tour of naval operations

in the Southwest Pacific and a stop at Pearl Harbor. Returning

to Washington, D.C., he made his report to President Roosevelt,

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, and the cabinet. In

response to Forrestal's elevated request that material

be sent immediately to the Southwest Pacific area, Stimson

(who was more concerned with supplying Operation Torch

in North Africa), told Forrestal, "Jim, you've

got a bad case of localitis." Forrestal shot

back in a heated manner, "Mr. Secretary, if the

Marines on Guadalcanal were wiped out, the reaction of

the country will give you a bad case of localitis in the

seat of your pants".

He

became Secretary of the Navy on May 19, 1944, after his

immediate superior Secretary Frank Knox died from a heart

attack. Forrestal led the Navy through the closing year

of the war and the painful early years of demobilization

that followed. As Secretary, Forrestal introduced a policy

of racial integration in the Navy.

Forrestal

traveled to combat zones to see naval forces in action.

He was in the South Pacific in 1942, present at the Battle

of Kwajalein in 1944, and (as Secretary) witnessed the

Battle of Iwo Jima in 1945. After five days of pitched

battle, a detachment of Marines was sent to hoist the

American flag on the 545-foot summit of Mount Suribachi

on Iwo Jima. This was the first time in the war that the

U.S. flag had flown on Japanese soil. Forrestal, who had

just landed on the beach, claimed the historic flag as

a souvenir. A second, larger flag was run up in its place,

and this second flag-raising was the moment captured by

Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal in his famous

photograph.

Forrestal,

along with Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Under Secretary

of State Joseph Grew, in the early months of 1945, strongly

advocated a softer policy toward Japan that would permit

a negotiated armistice, a 'face-saving' surrender. Forrestal's

primary concern was not the resurgence of a militarized

Japan, but rather "the menace of Russian Communism

and its attraction for decimated, destabilized societies

in Europe and Asia," and, therefore, keeping the

Soviet Union out of the war with Japan. So strongly did

he feel about this matter that he cultivated negotiation

efforts that some regarded as approaching insubordination.

His

counsel on ending the war was finally followed, but not

until the atomic bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima and

Nagasaki. The day after the Nagasaki attack, the Japanese

sent out a radio transmission saying that it was ready

to accept the terms of the allies' Potsdam Declaration,

"with the understanding that said declaration

does not comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives

of His Majesty as a sovereign ruler." That position

still fell short of the U.S. "unconditional surrender"

demand, retaining the sticking point that had held up

the war's conclusion for months. Strong voices within

the administration, including Secretary of State James

Byrnes, counseled fighting on. At that point, "Forrestal

came up with a shrewd and simple solution: Accept the

offer and declare that it accomplishes what the Potsdam

Declaration demanded. Say that the Emperor and the Japanese

government will rule subject to the orders of the Supreme

Commander for the Allied Powers. This would imply recognition

of the Emperor while tending to neutralize American public

passions against the Emperor. Truman liked this. It would

be close enough to 'unconditional.'"

In

the beginning of the Cold War period, Forrestal strongly

influenced the new Wisconsin Senator, Joseph McCarthy,

concerning infiltration of the government by Communists.

Upon McCarthy's arrival in Washington in December 1946,

Forrestal invited him to lunch. In McCarthy's words, "Before

meeting Jim Forrestal I thought we were losing to international

Communism because of incompetence and stupidity on the

part of our planners. I mentioned that to Forrestal. I

shall forever remember his answer. He said, 'McCarthy,

consistency has never been a mark of stupidity. If they

were merely stupid, they would occasionally make a mistake

in our favor.' This phrase struck me so forcefully that

I have often used it since."

Secretary

of Defense

In

1947, President Harry S. Truman appointed him the first

United States Secretary of Defense. Forrestal continued

to advocate for complete racial integration of the services,

a policy eventually implemented in 1949.

During

private cabinet meetings with President Truman in 1946

and 1947, Forrestal had argued against partition of Palestine

on the grounds it would infuriate Arab countries who supplied

oil needed for the U.S. economy and national defense.

Instead, Forrestal favored a federalization plan for Palestine.

Outside the White House, response to Truman's continued

silence on the issue was immediate. President Truman received

threats to cut off campaign contributions from wealthy

donors, as well as hate mail, including a letter accusing

him of "preferring fascist and Arab elements to the

democracy-loving Jewish people of Palestine." Appalled

by the intensity and implied threats over the partition

question, Forrestal appealed to Truman in two separate

cabinet meetings not to base his decision on partition,

whatever the outcome, on the basis of political pressure.

In his only known public comment on the issue, Forrestal

stated to J. Howard McGrath, Senator from Rhode Island:

"...no

group in this country should be permitted to influence

our policy to the point it could endanger our national

security."

Forrestal's

statement soon earned him the active enmity of some congressmen

and supporters of Israel. Forrestal was also an early

target of the muckraking columnist and broadcaster Drew

Pearson, an opponent of foreign policies hostile to the

Soviet Union, who began to regularly call for Forrestal's

removal after President Truman named him Secretary of

Defense. Pearson told his own protege, Jack Anderson,

that he believed Forrestal was "the most dangerous

man in America" and claimed that if he was not removed

from office, he would "cause another world war."

Upon

taking office as Secretary of Defense, Forrestal was surprised

to learn that the administration did not budget for defense

needs based on military threats posed by enemies of the

United States and its interests. According to historian

Walter LaFeber, Truman was known to approach defense budgetary

requests in the abstract, without regard to defense response

requirements in the event of conflicts with potential

enemies. The president would begin by subtracting from

total receipts the amount needed for domestic needs and

recurrent operating costs, with any surplus going to the

defense budget for that year. The Truman administration's

readiness to slash conventional readiness needs for the

Navy and Marine Corps soon caused fierce controversies

within the upper ranks of their respective branches.

During

the Reagan years, Paul Nitze reflected upon the qualities

which made a Secretary of Defense great: the ability to

work with Congress, the ability at "big-time management,"

and an ability at war planning. Nitze felt that Forrestal

was the only one who possessed all three qualities together.

Post-war

At

the close of World War II, millions of dollars of serviceable

equipment had been scrapped or abandoned rather than there

having been funds appropriated for its storage costs.

New military equipment en route to operations in the Pacific

theater was scrapped or simply tossed overboard. Facing

the wholesale demobilization of most of the US defense

force structure, Forrestal resisted President Truman's

efforts to substantially reduce defense appropriations,[18]

but was unable to prevent a steady reduction in defense

spending, resulting in major cuts not only in defense

equipment stockpiles, but also in military readiness.

By

1948, President Harry Truman had approved military budgets

billions of dollars below what the services were requesting,

putting Forrestal in the middle of a fierce tug-of-war

between the President and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Forrestal

was also becoming increasingly worried about the Soviet

threat. His 18 months at Defense came at an exceptionally

difficult time for the U.S. military establishment: Communist

governments came to power in Czechoslovakia and China;

the Soviets imposed a blockade on West Berlin prompting

the U.S. Berlin Airlift to supply the city; the 1948 Arab–Israeli

War after the establishment of Israel; and negotiations

were going on for the formation of NATO.

Dwight

D. Eisenhower recorded he was in agreement with Forrestal's

theories on the dangers of Soviet and International communist

expansion. Eisenhower recalled that Forrestal had been

"the one man who, in the very midst of the war, always

counseled caution and alertness in dealing with the Soviets."

Eisenhower remembered on several occasions, while he was

Supreme Allied Commander, he had been visited by Forrestal,

who carefully explained his thesis that the Communists

would never cease trying to destroy all representative

government. Eisenhower commented in his personal diary

on 11 June 1949, "I never had cause to doubt the

accuracy of his judgments on this point."

Forrestal

also opposed the unification of the military services

proposed by the Truman officials. Even so, he helped develop

the National Security Act of 1947 that created the National

Military Establishment (the Department of Defense was

not created as such until August 1949). With the former

Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson retiring to private

life, Forrestal was the next choice.

Resignation

as Secretary of Defense

Governor

of New York Thomas E. Dewey was expected to win the presidential

elections of 1948. Forrestal met with Dewey privately

and it was agreed, he would continue as Secretary of Defense

under a Dewey administration. Unwittingly, Forrestal would

trigger a series of events that would not only undermine

his already precarious position with President Truman

but would also contribute to the loss of his job, his

failing health, and eventual demise. Weeks before the

election, Pearson published an exposé of the meetings

between Dewey and Forrestal. In 1949, angered over Forrestal's

continued opposition to his defense economization policies,

and concerned about reports in the press over his mental

condition, Truman abruptly asked Forrestal to resign.

By March 31, 1949, Forrestal was out of a job. He was

replaced by Louis A. Johnson, an ardent supporter of Truman's

defense retrenchment policy.

Psychiatric

treatment

In

1949, exhausted from overwork, Forrestal entered psychiatric

treatment. The attending psychiatrist, Captain George

N. Raines, was handpicked by the Navy Surgeon General.

The regimen was as follows:

1. 1st week: narcosis with sodium amytal.

2. 2nd – 5th weeks: a regimen of insulin sub-shock

combined with psycho-therapeutic interviews. According

to Dr. Raines, the patient overreacted to the insulin

much as he had the amytal and this would occasionally

throw him into a confused state with a great deal of agitation

and confusion.

3. 4th week: insulin administered only in stimulating

doses; 10 units of insulin four times a day, morning,

noon, afternoon and evening.

According

to Dr. Raines, "We considered electro-shock but

thought it better to postpone it for another 90 days.

In reactive depression if electro-shock is used early

and the patient is returned to the same situation from

which he came there is grave danger of suicide in the

immediate period after they return... so strangely enough

we left out electro-shock to avoid what actually happened

anyhow".

Death

Although

Forrestal told associates he had decided to resign, he

was shattered when Truman abruptly asked for his resignation.

His letter of resignation was tendered on March 28, 1949.

On the day of his removal from office, he was reported

to have gone into a strange daze and was flown on a Navy

airplane to the estate of Under Secretary of State Robert

A. Lovett in Hobe Sound, Florida, where Forrestal's wife,

Josephine, was vacationing. Dr. William C. Menninger of

the Menninger Clinic in Kansas was consulted and he diagnosed

"severe depression" of the type "seen in

operational fatigue during the war". The Menninger

Clinic had successfully treated similar cases during World

War II, but Forrestal's wife Josephine, his friend and

associate Ferdinand Eberstadt, Dr. Menninger and Navy

psychiatrist Captain Dr. George N. Raines decided to send

the former Secretary of Defense to the National Naval

Medical Center (NNMC) in Bethesda, Maryland, where it

would be possible to deny his mental illness.[24] He was

checked into NNMC five days later. The decision to house

him on the 16th floor instead of the first floor was justified

in the same way. Forrestal's condition was officially

announced as "nervous and physical exhaustion,"

his lead doctor, Captain Raines, diagnosing his condition

as "depression" or "reactive depression."

National Naval Medical Center

As

a person who prized anonymity and once stated that his

hobby was "obscurity," Forrestal and his policies

had been the constant target of vicious personal attacks

from columnists, including Drew Pearson and Walter Winchell.

Pearson's protégé, Jack Anderson, later

asserted that Pearson "hectored Forrestal with innuendos

and false accusations."

Forrestal

seemed to be on the road to recovery, having regained

5.5 kg (12 pounds) since his entry into the hospital.

However, in the early morning hours of May 22, his body,

clad only in the bottom half of a pair of pyjamas, was

found on a third-floor roof below the 16th-floor kitchen

across the hall from his room. Forrestal's last written

statement, which some have alleged was an implied suicide

note, was part of a poem from Sophocles' tragedy Ajax:

Fair Salamis, the billows’ roar,

Wander around thee yet,

And sailors gaze upon thy shore

Firm in the Ocean set.

Thy son is in a foreign clime

Where Ida feeds her countless flocks,

Far from thy dear, remembered rocks,

Worn by the waste of time–

Comfortless, nameless, hopeless save

In the dark prospect of the yawning grave....

Woe to the mother in her close of day,

Woe to her desolate heart and temples gray,

When she shall hear

Her loved one’s story whispered in her ear!

“Woe, woe!’ will be the cry–

No quiet murmur like the tremulous wail

Of the lone bird, the querulous nightingale–

The

official Navy review board, which completed hearings on

May 31, waited until October 11, 1949, to release only

a brief summary of its findings. The announcement, as

reported on page 15 of the October 12 New York Times,

stated only that Forrestal had died from his fall from

the window. It did not say what might have caused the

fall, nor did it make any mention of a bathrobe sash cord

that had first been reported as tied around his neck.

According to the full report, which was not released

by the Department of the Navy until April 2004, the

official findings of the board were as follows:

After full and mature deliberation, the board finds as

follows:

FINDING OF FACTS

• That the body found on the ledge outside of room

three eighty-four of building one of the National Naval

Medical Center at one-fifty a.m. and pronounced dead at

one fifty-five a.m., Sunday, May 22, 1949, was identified

as that of the late James V. Forrestal, a patient on the

Neuropsychiatric Service of the U. S. Naval Hospital,

National Naval Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland.

• That the late James V. Forrestal died on or about

May 22, 1949, at the National Naval Medical Center, Bethesda,

Maryland, as a result of injuries, multiple, extreme,

received incident to a fall from a high point in the tower,

building one, National Naval Medical Center, Bethesda,

Maryland.

• That the behavior of the deceased during the period

of his stay in the hospital preceding his death was indicative

of a mental depression.

• That the treatment and precautions in the conduct

of the case were in agreement with accepted psychiatric

practice and commensurate with the evident status of the

patient at all times.

• That the death was not caused in any manner by

the intent, fault, negligence or inefficiency of any person

or persons in the naval service or connected therewith.

James

Forrestal is buried in Section 30 Lot 674 Grid X-39 of

Arlington National Cemetery.

Assassination

theories

Doubts

have existed from the beginning about Forrestal's death,

especially allegations of homicide.[30] The early doubts

are detailed in the book The Death of James Forrestal

(1966) by Cornell Simpson, which received virtually no

publicity. As Simpson notes (pp. 40–44), a major

reason for doubt is the fact that the Navy kept the full

transcript of its official hearing and final report secret.

Additional doubt has been raised by the 2004 release of

that complete report, informally referred to as the Willcutts

Report,[31] after Admiral Morton D. Willcutts, the head

of NNMC, who convened the review board.

There

were unsubstantiated reports in the press[32] of paranoia

and of involuntary commitment to the hospital, as well

as suspicions[33] about the detailed circumstances of

his death, which have fed a variety of conspiracy theories

as well as legitimate questions. For example, among the

discrepancies between the report and the accounts given

in the principal Forrestal biographies are that the transcription[34]

of the poem by Sophocles appears to David Martin, author

of the six-part series Who Killed James Forrestal? to

have been written in a hand[36] other than Forrestal's.

If Forrestal's, according to some intelligence sources,

then he could not scribble the word "nightingale"

in the poem because it was the code name of the Ukrainian

Nazi elite unit Nachtigall Brigade which Forrestal had

helped to smuggle to the United States to supplant Kim

Philby's failed ABN (Anti Bolshevik Nationals), an MI6

Soviet émigré fascist group.[37] There was

also broken glass found on Forrestal's bed, a fact that

had not been previously reported. Theories as to who might

have murdered Forrestal range from Soviet agents, to U.S.

government operatives sent to silence him for his knowledge

of UFOs.

Forrestal's

single known public statement regarding pressure from

interest groups, and his cabinet position opposing the

partition of Palestine has been significantly magnified

by later critics into a portrayal of Forrestal as a dedicated

anti-Zionist who led a concerted campaign to thwart the

cause of the Jewish people in Palestine. These critics

tend to characterize Forrestal as a mentally unhinged

individual, a hysteric with deep anti-Zionist and anti-Jewish

feelings. Forrestal himself maintained that he was being

shadowed by "foreign men", which some critics

and authors quickly interpreted to mean either Soviet

NKVD agents or proponents of Zionism.[40] Author Arnold

Rogow supported the theory that Forrestal committed suicide

over fantasies of being chased by Zionist agents, largely

relying on information obtained in interviews conducted

with some of Forrestal's fiercest critics inside and outside

the Truman administration.

However,

those who see Zionist conspiratorial designs behind Forrestal's

unexplained death note Rogow's footnote to his work:

"While

those beliefs reflect the fact that Forrestal was a very

ill man in March 1949, it is entirely possible that he

was 'shadowed' by Zionist agents in 1947 and 1948. A close

associate of his at the time recalls that at the height

of the Palestine controversy, his (the associate's) official

limousine was followed to and from his office by a blue

sedan containing two men. When the police were notified

and the sedan apprehended, it was discovered that the

two men were photographers employed by a Zionist organization.

They explained to the police that they had hoped to obtain

photographs of the limousine's occupant entering or leaving

an Arab embassy in order to demonstrate that the official

involved was in close contact with Arab representatives."

Columnists

Drew Pearson and Walter Winchell led a press campaign—which

many would today find libelous—against Forrestal

to make him appear paranoid. But official evaluations

of his psychiatric state never mentioned paranoia. One

of Pearson's most spectacular claims was that at Hobe

Sound, Florida, shortly before he was hospitalized, Forrestal

was awakened by a siren in the middle of the night and

ran out into the street exclaiming, "The Russians

are attacking." No one who was there that night confirmed

this claim. Captain George Raines, the Navy doctor in

charge of Forrestal's treatment, called it an outright

fabrication.

The

first US ambassador to Israel James G. McDonald writing

in 1951 describes the attacks on Forrestal as "unjustifiable",

"persistent and venomous" and "among the

ugliest example of the willingness of politicians and

publicists to use the vilest means - in the name of patriotism

- to destroy self-sacrificing and devoted public servants.

Sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Forrestal